before pride: the long arc of queer resistance

This June, Washington D.C. hosts WorldPride for the first time. The theme - “The Fabric of Freedom” - is ambitious in its reach: it evokes a language of interdependence, collective struggle, and the unfinished project of queer liberation. The occasion marks the fiftieth anniversary of Pride in the U.S. capital and comes at a time when the legal and cultural landscape for LGBTQ+ people, both in the United States and globally, is shifting once again - unevenly, and not always forward, obviously.

The context this year is hard to ignore. Across the country and the world, a wave of legislation has emerged targeting queer - especially trans people’s access to health care, public life, and legal recognition. More than twenty states now ban gender-affirming medical care for minors. Others have passed laws limiting trans people’s ability to update identity documents, participate in school sports, or access public facilities like bathrooms and shelters.

Pride emerged in response to precisely this kind of moral and institutional hostility. Though commonly associated with Stonewall and the late 1960’s, the signals that while Stonewall is historically important, the underlying reasons for Pride were already present for decades, even centuries, obviously. It is grounded in the assertion of personhood and humanity under constraint in refusing criminalisation, pathologization, and invisibility. What began as a local act of resistance soon took on international significance, as it unfolded within a country that had long positioned itself as a cultural and political model for the Western world.

Obviously, the United States still plays an outsized role in shaping global political and cultural narratives. The U.S. continues to shape global norms - not just through diplomacy or law, but though entertainment, language, technology, and media in general. American pop culture doesn’t just reflect social trends - it exports them. From films and streaming series to music, social media, and advertising, the U.S. still function as a central nervous system for the cultural West. And when the cultural center begins to signal that queer lives are once again negotiable, that signal travels - quickly.

Europe, in particular, has long positioned itself as socially progressive, but it has also looked to the U.S. for its cultural language. Since the Second World War, much of Western Europe has absorbed American norms - consciously or not - through Hollywood, journalism, activism, the music industry, and social media. Few LGBTQ+ rights movements across the Western World have been untouched by American influence. So, when that influence begins to shift - when Pride itself becomes controversial at a big scale in the country that once helped elevate it - there are ripple effects far beyond national borders.

So now we look back at the longer history that brought us here: how Pride began, what it responded to, and why it remains necessary. Why does the U.S. hold a central point in the story? And why is pride not for debate, but a fundamental human right and not a matter of political preference. It is not about lifestyle, opinion, or riot. It is a collective demonstration of rights that are foundational: the right to exist as oneself, safely, and freely, in public. That is not a “side” in debate - it is a human birthright.

Pride is not for debate (© Edie Lou)

Queer and Trans Histories: A Longer Arc

Long before the legal language of LGBTQ+ identities emerged, people around the world lived in ways that defied binary gender roles and heteronormative expectations. Many cultures around the world recognized gender plurality, same-sex intimacy, and non-binary social roles as part of the human condition. In many indigenous North American nations, Two-Spirit individuals - those embodying both masculine and feminine roles - held ceremonial and social authority. In South Asia, the Hijra community has existed for centuries, occupying recognized roles in religious and cultural life. The Zapotec of Oaxaca have long honoured Muse as a third gender, without stigma or marginalization. These configurations were not fringe exceptions - they were embedded in social systems. Their suppression came not through evolution or biological explanation, but through force: the combined machinery of colonialism and the bureaucratic state.

The inclusivity of queer and trans life was not unique to the colonial world. In Europe itself, the historical record tells a far more complex story than the dominant moral narrative suggests. In Ancient Greece, same-sex relationships - particularly between men - were not only accepted but, in some cases, institutionalized. The Symposium of Plato described male love as a gateway to the divine. The Sacred Band of Thebes, a renowned military unit composed of male couples, fought on the belief that lovers would defend one another with exceptional loyalty. Mythology also affirmed gender and erotic fluidity: Zeus abducted the Trojan prince Ganymede as his lover; Apollo mourned the death of his beloved Hyacinthus by transforming him into a flower; and the androgynous Hermaphroditus embodied the merging of male and female. The prophet Tiresias lived as both man and woman, and certain cults worshipped Aphrodite in both feminine and masculine forms.

Roman culture, while deeply hierarchical, also left behind a record of gender and sexual variance that resists contemporary assumptions of silence or shame. Emperors like Hadrian openly mourned and deified their male lovers - Antinous became a god in death, his likeness carved into statue across the empire. Nero is reported to have publicly married male partners on at least two occasions, once even signing himself the role of bride. The short reign of Elagabalus introduced open gender nonconformity at the highest level of power, with sources describing the emperor wearing cosmetics, adopting feminine dress, and reportedly seeking surgical transformation.

While Roman norms distinguished between active and passive sexual roles in ways that reinforced class and dominance, queer expression was neither invisible nor absent in civil life. It appeared in poetry, political satire, and imperial spectacle - not as marginal deviation, but as part of Rome’s complex negotiation between desire, status, and identity. Gender and sexual variance were not socially peripheral, deviant, or hidden in Ancient Greek or Roman culture. They played a role in shaping normative public institutions: religion, politics, education, and the arts we still worship today.

Nero is reported to have publicly married male partners (©Edie Lou)

Medieval Europe and the New Age

While the fall of Rome and the rise of Christianity as Europe’s dominant moral and legal authority, queerness was pushed from visibility into heresy. The early medieval period saw a gradual but systematic consolidation of ecclesiastical power, where the church not only governed belief but shaped legal doctrine. Homoerotic acts were no longer treated as questions of social status or personal behavior - they became sins against divine order. Canon law increasingly defined same-sex intimacy as “sodomy”, a term that blurred acts, identities, and imagined transgressions into a single category of moral threat. By the High Middle Ages, these laws were adopted into secular legal codes, with punishment ranging from penance to execution.

Gender nonconformity, too, became grounds for suspicion: cross-dressing could be construed as deception or demonic possession, and accusations of heresy often included implications of sexual deviance. Yet despite the tightening grip of theological and legal surveillance, queer lives persisted - in monastic writings, mystic visions, trial records, and folklore. The medieval period did not erase queerness; it redefined it as unspeakable, and the attempted to legislate its silence.

Despite criminalization and moral condemnation, queer life in medieval and early modern Europe did not vanish - it adapted. Hidden networks emerged through monasteries, mystic circles, quilts, and elite courses, where intimacy could pass as spiritual friendship that read today as deeply homoerotic. Hildegard von Bingen’s ecstatic visions spoke of divine androgyny and reigned embodiment far beyond binary norms. Her correspondence with women also reflects deep emotional entanglement, expressed in the language of devotion.

Trial records, too, offer a fragmented archive: Joan of Arc was condemned in part for wearing male military dress, and Inquisitorial court preserved records of same-sex acts prosecuted as sodomy across Spain, Italy, and France. Cross-dressing trials occurred in cities like Venice, London, and Antwerp, where individuals - often assigned female at birth - dressed and lived as men, sometimes marrying women. While many faced legal consequences, the records themselves reveal a history of gender, variance long before contemporary trans identity. And a quiet hypocrisy.

Just let us observe the theater in early modern England. In the 17th century theater became a public laboratory of gender performance. With women barred from the stage until the Restoration, all female roles were played by boys or men - often trained to heighten and stylize femininity in ways that mimicked and exaggerated gender norms. Edward Kynaston, one of the last and most acclaimed of these “boy players”, became renowned for his portrayals of women so compelling that he reportedly moved between masculine and feminine presentation offstage as well, attracting both admiration and fascination. These performances shaped a tradition of gender play that would echo centuries later in the aesthetics of drag. The fascination with femininity performed by masculine bodies became a form of sanctioned spectacle - staged, celebrated, and applauded - while outside the theatre, individuals who dressed across gender lines could be arrested, tried, and punished. This split - between performance and prosecution, illusion and identity - underscores how power tolerated gender variance only when safely distance through class and costume.

Even at the highest level of power, same-sex desire persisted behind layers of decorum, as seen in King James l’s romantic attachment to George Villiers and Queen Anne’s emotionally charged relationships with Sarah Churchill and Abigail Masham. These patterns suggest a system that publicly condemned what it privately tolerated, redirected, or suppressed. Steered by the authority of the Christian Church, which shaped legal codes, moral norms, and conceptions of society, created a double moral cloaked in hierarchy and silence.

Boston Marriage (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

Between Science and Surveillance - The 19th Century

The 19th century marked a turning point in how queer life was framed - no only by religious or legal authorities, but by science. Early advocates like Karl Heinrich Ulrichs argued that same-sex attraction was natural, rooted in a “female soul in a male body”. He used language available to him at the time to explain that homosexuality was inborn, natural, intrinsic part of who a person is - not a sinful choice or a criminal behavior.

Magnus Hirschfeld, a Jewish-German physician, sexologist, and one of the most influential early figures in the scientific study and political defense of sexual and gender diversity, also defended homosexuality and trans identities as part of natural human variation. He founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin 1919, defined the term sexual intermediaries, the term “third sex”, and supported what today we’d call trans rights, even facilitating some of the earliest known gender-affirming surgeries. Their goal was protective: to defend queer people from criminal punishment and moral condemnation by offering scientific arguments for acceptance.

By the final decades of the 19th century, the early emancipatory efforts of Ulrichs and Hirschfeld were being overtaken by a more insidious logic. The 19th century saw in general an enormous transformation in science - in discovery, but also in its social power. In many ways, this period laid the groundwork for modern systems of knowledge and surveillance. The major developments shaped its system were: taxonomy and classification - this era produced Darwin’s theory of evolution (1859), which fueled efforts to rank species - and humans - according to supposed natural laws, anthropology and phrenology, which tried to classify humans by race, skull shape, and behavior, and it was the beginning of scientific racism and eugenics, attempting to “improve” the population by controlling reproduction.

By the late 1800’s, thinkers in medicine and the emerging field of psychology began to study sexuality as a mental and physical condition. Richard von Krafft-Ebing categorized in his book, Psychopathia Sexualise (1886), sexual “deviations”, including homosexuality, sadism, and masochism. Scientist replaced theological judgement with clinical observation. Instead of sin, we had “perversion”. Instead of hell, we had hospitalization or legal punishment.

One of the most prominent legal cases of the Victorian era was the prosecution of Oscar Wilde. In Britain, the 1885 Labouchere Amendment introduced the charge of “gross indecency”, a loosely defined legal category that criminalized any sexual or affectionate behavior between men. Unlike older sodomy laws, which required proof of specific acts, this statue allowed for prosecution based on innuendo, correspondence, or reputation alone.

It was under this provision that Oscar Wilde, the writer of The Picture of Dorian Grey, was convicted in 1895, following a failed libel suit against the Marquess of Queensberry. Wilde’s relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, and his perceived defiance of social norms, were treated as sufficient grounds for criminal punishment. Though no clearly defined offence could be proven, Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor. The trial ruined him socially and financially. He died in exile, impoverished and humiliated in 1900. Because of Wilde’s cultural prominence, his trial became a high-profile demonstration of how the state would treat public expressions of same-sex desire.

Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

Beginning of the 20th century and WWII

Oscar Wilde’s 1895 conviction signaled a shift. In the decades that followed this approach would be expanded through surveillance, psychiatric diagnosis, workplace purges - but also met, increasingly, with adaptive strategies from within queer life. But even as the law punished Wilde for what it refused to name, queer lives continued. Among women, a different kind of strategy emerged. In New England, so-called Boston marriages - long-term domestic partnerships between highly educated women. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, women were widely believed to be less sexual than men - almost asexual by nature. Emotional intimacy between women was often seen as natural, innocent, or even morally elevating.

The possibility that such closeness could be erotic or romantic was simply not part of the dominant worldview, especially among elites and moral authorities. The term “Boston marriage” came into use because so many of these relationships were seen among the intellectual elite in Boston and greater New England, particularly among college-educated women. The term was first popularized in fiction, notably in Henry James’s novel The Bostonians (1886). Within that cultural framework two women living together did not raise alarm as long as they remained discreet, and did not publicly challenge gender roles, their relationships could continue without legal or moral intervention. Not because they were accepted, but because they were not fully understood. Sex between women, however, was not included. This was not because of tolerance - it was because many lawmakers, reportedly including Queen Victoria herself, refused to believe that lesbianism even existed.

Across the Atlantic, queer lives emerged through culture as much as identity. Parisian salons hosted by Gertrude Stein’s literary salons, Natalie Clifford Barney’s gatherings, and the private circles of Jean Cocteau and Radclyffe Hall nurtured networks of writers, artists, and exiles experimenting with gender and kinship and shaped the avant-garde. Meanwhile, in Harlem, the cultural vitality of the Harlem Renaissance allowed queer Black writers and musicians to articulate lives that defied racial and sexual boundaries - albeit often through coded language and indirect representation. Nightlife in Weimar, Berlin and cabaret circuits in New York and Chicago offered temporary stages of freedom, until repression inevitably followed.

Under Nazi Germany and Europe, these systems became tools of annihilation. In 1935, the regime expanded Paragraph 175, criminalizing even the suggestion of same-sex desire between men. An estimated 100.000 were arrested at least; about 15.000 were sent to concentration camps. There, many dies - unprotected by postwar reparations, their suffering erased from Holocaust memory. Queer women were targeted through a different lens, often deemed “asocial” or deviant. These women could be arrested, surveilled, or institutionalized - and many were sent to concentration camps, especially Ravensbrück, the largest women’s camp. While gay men were marked with the pink triangle, some queer women were classified as “asocial” and forced to wear the black triangle, a vague category applied to sex workers, Roma, Sinti and Yenish women, political resisters, and other.

Meanwhile, Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science - the world’s first to offer trans care - was looted and burned. Queerness was no longer just criminalized; it was framed as a direct threat to the ideological foundations of the state. It challenged the authoritarian model of social order, disrupted the regime’s obsession with racial and reproductive “purity”, and was treated as a biological defect that weakened the national body.

The Pre-Stonewall Era: 1950s to 1969

In the years following World War II, queer and trans life in the United States and Europe existed under intense scrutiny. The Cold War intensified a culture of suspicion: in the U.S., the “Lavender Scare” parallel McCarthyist purges, leading to the mass firing of federal employees accused of homosexuality and any `non-normative` sexual or gender expression. Queer identity was cast not only as immoral but untrustworthy - an existential threat to national security. At the same time, medical institutions continued to pathologies same-sex desire and gender nonconformity. Homosexuality and queerness remained listed as a mental disorder in diagnostic manuals; so-called treatments ranged from psychoanalysis to electroshock therapy.

And yet, in this atmosphere of repression, forms of community-building and resistance quietly intensified. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950 by Harry Hay, was one of the first sustained homosexual rights organizations in the U.S. Its founders believed that public opinion could be shifted by presenting homosexuals as respectable, assimilated, and harmless. A few years later, the Daughters of Bilitis formed as a counterpart for lesbians, focusing on support networks and self-education. Both groups were cautious - prioritizing discreet advocacy and legal reform over open protest - but they laid essential groundwork for what came next.

Parallel to these efforts, the most marginalized members of the queer community - particularly trans people, drag performers, sex workers, and queer youth - lacked access to such respectable avenues. Their lives were lived in public space, often without institutional protection, and their resistance was shaped by necessity, obviously. In 1959, queer patrons at Cooper’s Donuts in Los Angeles fought back against routine police harassment. It became the site of one of the earliest documented acts of organized queer resistance in the United States. Cooper’s was frequented by mix of queer and trans people, including drag performers, trans women, and street-based queer youth - many of whom lived on the margins and often faced routine harassment by the LAPD.

In 1966, at Comton’s Cafeteria in San Fransisco, trans women and drag queens fought back during another police raid - breaking windows, flipping tables, demanding recognition. Compton’s wasn’t widely recognized for decades, partly because the participants - mostly poor, trans, and people of color - were excluded from mainstream queer historical narratives though. But it marked a shift from quiet endurance to active resistance - it catalyzed a wave of organizing efforts in the city, shifting trans and queer resistance from survival to structured political advocacy.

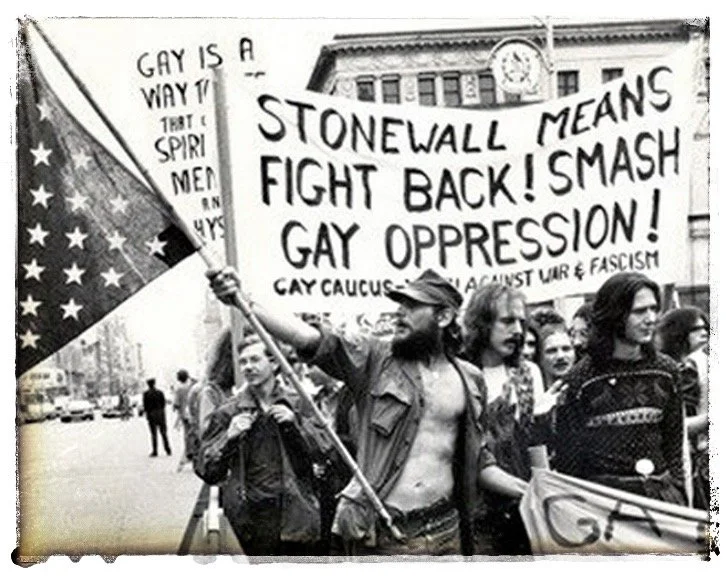

Then came the Stonewall Uprising (©of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

Then came the Stonewall Uprising. On the night of June 28, 1969, when police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village, they encountered a community no longer willing to comply. What followed was six nights of resistance led primarily by those furthest from societal protection: trans women, Black queer youth, sex workers, and homeless people. Unlike previous raids, the crowd resisted, and the tension escalated for six days. The protests continued in the surrounding streets for several nights, growing media attention, and an increasing sense of political urgency. The uprising reflected years and decades of marginalization, dehumanization, and escalating tensions between queer communities and law enforcement. Stonewall marked a shift. It moved dissent from private networks and survival into public space and political strategy. The uprising was followed by the formation of radical organizations like the Gay Liberation Front and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR).

Queerness, no longer hidden or pathologized in silence, emerged as a political category with claims to space, dignity, and future. One year later, in 1970, the first Christopher Street Liberation Day took place - a march to remember the uprising and to assert the right to live visibly, safely, and without explanation. Pride was born. It emerged as a declaration of the fundamental right to live freely and authentically - without discrimination or punishment.

The Right to Be: Identity, Repression, and Human Dignity

We have now examined, across centuries and continents, a sobering truth: that queer and trans people have not merely been excluded, but systematically hunted - for how they lived, how they identified, and whom they loved. People were - and in many places still are - punished for existing. For expressing something that is, by definition, their own.

What emerges from this is not only the resilience of queer communities during centuries, but also a more enduring contradiction: the entanglement of authority and repression. As we have seen, queerness and gender plurality were not peripheral, marginalized groups in society - they were embedded in the social, spiritual, and aesthetic life of earlier civilizations. Ancient societies like Greece and Rome integrated same-sex relationships and non-binary roles without sanctions. It was with the rise of Christian hegemony in medieval Europe that a reversal took hold. What had once been lived and visible became unspeakable - redefined as threat, sin, or disorder, with lasting cultural, psychological, and transgenerational trauma. A culture of double standards emerged: the same institutions, the same Church that condemned sodomy and nonconformity also shielded institutional abuses for centuries; the same courts and societies that criminalized gender variance allowed it to flourish in spaces like the theatre, where male actors performing female roles became both spectacle and social release.

This contradiction between repression and institutional power has been examined by thinkers such as Judith Butler. In Gender Trouble (1990), Butler argued that gender is not a fixed identity but a performance - socially constructed through repeated behaviors, norms, and expectations. “There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very expressions that are said to be its results”. Gender - and by extension the stability of the dominant categories of gender and sexuality such as heterosexuality, monogamy and binary gender roles - is not born of some inner essence but produced and reinforced through repeated social performance. Once queerness reveals that these norms have to be performed - rather than being naturally given - it shows just how fragile and constructed they are. That fragility often triggers anxiety and reaction from institutions invested in keeping those norms intact as a form of control.

Butler has noted that for many, especially white heterosexual men, queerness reveals the fragility of their own position within structures of power and control. The normative structures of marriage, family, and masculinity begin to appear less self-evident - and more performative. The anxiety this produces is displaced mostly outward, reemerging in the form of moral panic, legislative backlash, or ideological rhetoric. Repression functions not only to silence others but to shield dominant groups from having to confront the contingency of their own status. So, when someone identifies as queer or lives outside those categories, it does not just challenge individual prejudice - it reveals that these supposedly “natural” roles are actually (white)-man-made, fragile, and maintained by systems of power.

Until then the Pride goes on (©Edie Lou)

Birthright & The Right to Belong

If queerness challenges the foundation of identity categories, as Judith Butler suggests, then it does so not by standing outside humanity - but by insisting on full inclusion within it. Queer people are not asking for `special treatment `; they are affirming a simple fact: they are human. And the rights that apply to human beings apply to them. That is the principle at the heart of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948 under the leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt and in direct response to the atrocities of World War II. The UDHR emerged as a foundation document meant to protect dignity against systems of dehumanization, authoritarianism, and discrimination.

Article 1 states unequivocally: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Article 2 guarantees those rights to everyone, without distinction of “race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” Article 3: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person”. Queer and trans people are not outside the framework - they are just as every human being entitled to the full scope of rights, dignity, and freedom. To exist freely and safely in one’s body, identity, and relations is not a privilege. It is the baseline of human dignity and a birthright.

So, if the recognition of queer identity as a basic human right is to have force beyond paper, then the behavior of powerful nations - especially one as culturally and politically dominant as the United States - matters profoundly. Because of its enduring global influence, the U.S. functions not only as a political power but as a cultural and ideological bellwether. through its court rulings, media industries, and social networks such as Hollywood, Netflix, Facebook, Instagram etc., it shapes global discourse - consciously or subconsciously - curating taste, influencing behavior, and setting precedents which rights, values, and social norms are perceived as legitimate, negotiable, or disposable.

For much of the postwar era, the U.S. was perceived as a vanguard of liberal democratic values. Its cultural exports shaped not only global policy, but the imagination of what freedom looked like. Now, as American politics lurch toward restriction, much of Europe - where religious conservatism, bureaucratic caution, and nationalist undercurrents remain embedded in its political DNA - risks following that lead. The trend is already visible in the resurgence of far-right rhetoric and policy across the continent, form Orbán’s Hungary to rising parties in France, Italy, and Germany.

When the U.S. reaffirms the dignity and legitimacy of queer life, it sets a global standard. But when it withdraws rights, it gives license to repression elsewhere. The rollback of protections in America does not remain confined within its borders. In a globalized world, the retreat of one democracy becomes the alibi of others. And in that sense, what is happening in the U.S: is not just a domestic backlash. It is an international warning.

Because when any nation with global influence reconsiders the dignity of queer life, it signals to the world that such dignity is negotiable. And so long as that signal echoes - whether through law, media, or silence - the work of insisting on visibility, autonomy, and equality must continue. When the right to live openly, to love freely, and to define one’s identity without fear is no longer up for debate - when these are recognized no as special claims but birthrights - the need to defend them will finally recede, Until then, the Pride goes on.

https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

https://vcresearch.berkeley.edu/faculty/judith-butler

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/85767.Gender_Trouble

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10065595-a-queer-history-of-the-united-states

https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/dubermanstonewall.html

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1875.The_History_of_Sexuality_Volume_1

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo22782232.html

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/161634.Christianity_Social_Tolerance_and_Homosexuality

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/30011283

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/553309.Bisexuality_in_the_Ancient_World

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/1085827.Homosexuality_in_Greece_and_Rome

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/women-latin-poets-9780199229734?cc=ch&lang=en&

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/340577.The_Greatest_Benefit_to_Mankind

https://books.google.ch/books/about/Magnus_Hirschfeld.html?id=9eHOAgAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/352454.The_Riddle_of_Man_Manly_Love

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/616066.Talk_on_the_Wilde_Side

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5294.Oscar_Wilde

https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20050726-giles.pdf

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/31248/summary

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/bib244171

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/14958.Gertrude_and_Alice

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/135038.Women_of_the_Left_Bank