punk as a symptom of sanity: On refusal & authorship

Richard Hell once sang, “I belong to the blank generation.” he was making a statement - it was a declaration of autonomy, wasn´t it? Nearly five decades later, that sentiment still resonates. Punk endures, and we like it, we are fascinated by it. Not just because it embodies a timeless refusal to conform. There is something else behind. There is something unsettling about how easily punk gets absorbed into the very systems it once rejected. What once began as a raw rejection of conformity - a refusal to polish, to please, to participate - has been repackaged as an aesthetic. The safety pins, the attitude, the DIY grit are now sold back to us through runway collections and nostalgia-driven playlists.

It is hard not to be suspicious of how obsessed the system remains with punk´s image - especially when it was never meant to be marketable. The very culture punk rejected now parades its aesthetics down the catwalk. Designers reference it. Editors revisit it. Retailers repackage it.

Punk has never been easy to define. From the beginning, it resisted categorization - stylistically, politically, culturally. It emerged in the mid-1970´s in New York and London, not with a singular ideology, but as a rupture: a sharp refusal of the norms governing society. Punk was improvised, fragmented, contradictory and raw. What is striking is not just that punk has survived, but that it continues to compel attention. It remains subject of cultural adaptations, new subgenres, and of fashion retrospectives. Its original gestures - rejection, disobedience, rawness - have been endlessly interpreted, co-opted, and reimagined. And the fascination persists.

I Belong to the Blank Generation (©picture: Edie Lou)

But why?

Why does punk, a culture built on contradiction and rejection, still hold so much weight? Why does it keep resurfacing in art, politics, fashion, language? What accounts for its staying power - not just as a style, but as an idea? What is it about punk that continues to attract new generations, long after its emergence. Is it the sound? The attitude? The aesthetic? Or is it something harder to name?

Maybe it has something to do with the way punk handled identity and authenticity. With how it made space for presence, not performance. With how it let people show up without asking to be understood. It didn´t promise transformation. It didn´t sell a dream. No future, baby…What it offered - if it offered anything - was permission. To speak in noise. To reject the script. To be something other than what the world wanted to turn you into.

Identity as Refusal

Let’s face this: Contemporary institutions do not only manage behavior - they manage the so called “identity”. Through schools, markets, media, and digital platforms, individuals are positioned in ways that reduce complexity to function: student, worker, consumer, profile, etc. These positions are not inherently false, but when imposed as totalling, they cease to reflect a lived self. What remains is not identity, but administration - a form of externally imposed legibility that flattens difference, contradiction, and autonomy.

Stuart Hall´s work brings a little clarity into this dynamic. Identity, he argues, is not an inner truth but a process of positioning - shaped by discourse, history, and systems of power. But when those systems fix the subject into narrow, functional categories, what they produce is not identity in any meaningful sense. It is objectification: the individual as unit, sorted and interpretable, but no longer self-directed. In Hall´s terms, punk did not express that type of identity, it produced a space in which real identity could exist without having to be resolved into coherence.

Punk, obviously, refused this condition. Punk did not write essays about identity politics. It wore torn clothes, made dissonant music, took up space without softening, and showed up as something that didn´t fit. Spit in the face. It did not try to explain why the system´s demand for clarity or interpretability was wrong. It simply refused to comply. It made itself unreadable through messiness, contradiction, and refusal to fit in. It is about agency through disruption - punk asserting the right to exist without being decoded, categorised, or explained.

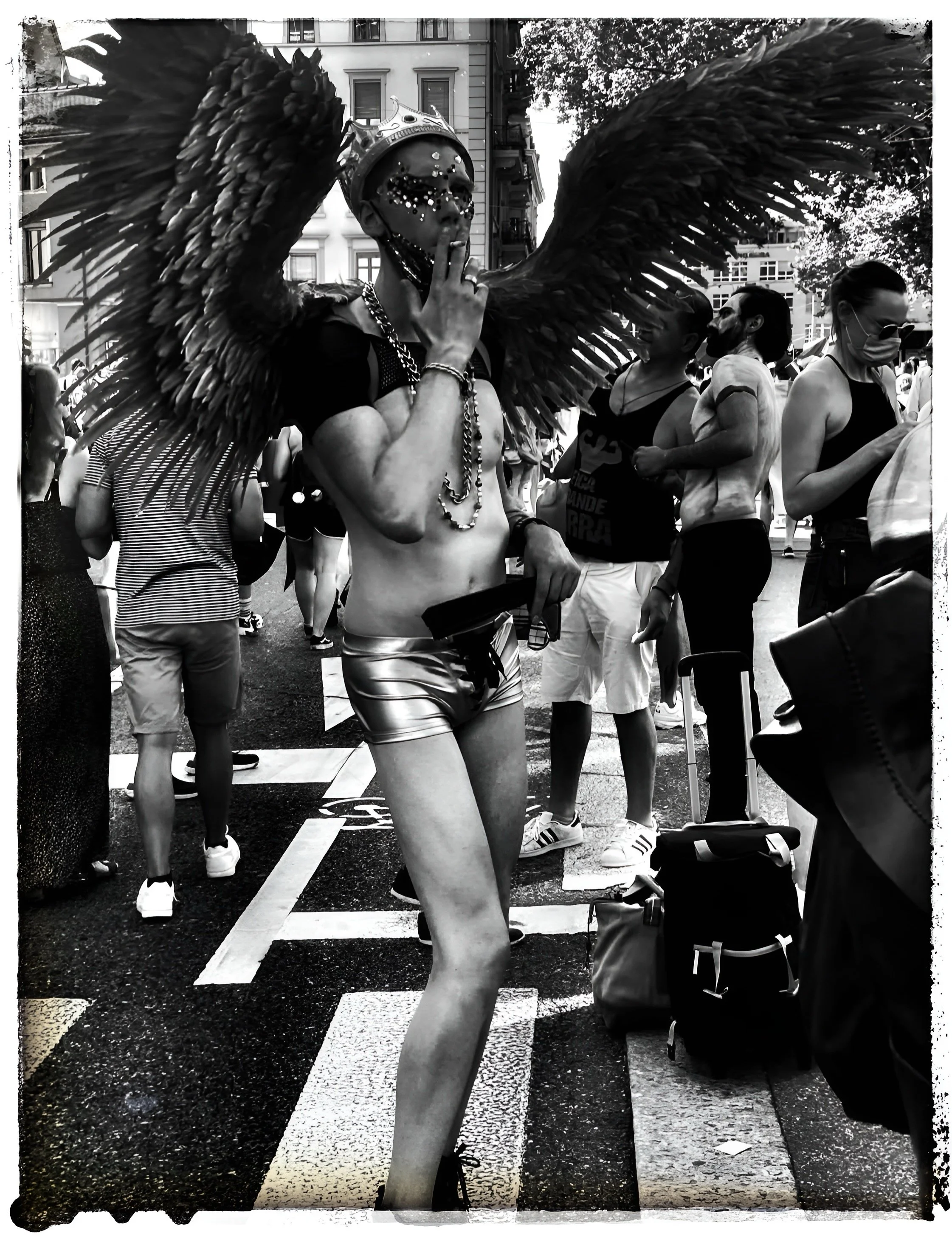

Identity as Refusal (©picture: Edie Lou)

Punk as a Symptom of Sanity

Let’s talk about the chaos it created. As we all know: it is often assumed that punk emerged from chaos - an expression of nihilism, delinquency, or cultural collapse. But let´s locate the disorder. Punk was not the crisis. It was a response to crisis: a collective and intelligent refusal of systems that no longer functioned, yet continued to demand performance and compliance.

To live in a society that requires constant self-curation - and then withholds recognition unless that curated self fits dominant expectations - produces not just inequality, but distortion. Punk made this distortion visible. So…Punk was a form of psychic resistance. It resembled the adaptive refusal seen in other overdetermined environments: the way individuals respond to authoritarian schooling, or disengage from bureaucratic systems that deny agency. These are not breakdowns. They are boundary-setting behaviors - often disruptive, but grounded in the preservation of selfhood.

Michael Foucalt´s later work on counter-conduct is instructive here. He argued that contemporary institutions - schools, workplaces, prisons, medical systems - do not simply control behavior; they shape identity through processes of normalization, surveillance, and visibility. In such systems, to be seen is often to be sorted, disciplined, and managed. Foucalt´s concept of counter-conduct describes not organised revolution, but refusal at the level of subjectivity. It is the rejection of how one is supposed to behave- appear, or self-regulate. Punk can be read as a form of counter-conduct: a refusal to be interpretable within the systems that demand coherence and participation

It did not reject power in the abstract. It rejected the way power was enacted in daily life - through school, work, gender roles, fashion, language. Punk withdrew from the obligation to be optimized, visible, and self-marketable. Its disorder was not dysfunction. It was a coherent rejection of the processes that turn people into objects of social management.

Its aesthetic volatility, its rejection of careerism, its refusal to self-explain - these were not signs of collapse. They were ways of preserving identity and dignity in a culture that increasingly demanded performance over authenticity. Punk was not anthology. It was a rational withdrawal from a system that had already ceased to offer reciprocal recognition.

Semiotic Sabotage (©picture: Edie Lou)

Style as Interruption

But what about the optics? Punk style is easy to spot but harder to pin down - not so much a look as a way of stepping into the world sideways. Safety pins, torn shirts, Mohawks, combat boots, improvisational disorder. But these elements were - obviously - not simply aesthetic choices. They were strategic refusals - a form of cultural noncompliance enacted on the body. Unlike other subcultures, punk refused the framework itself. It interfered with legibility. It created discomfort not just through content, but through form - through appearing as something that could not be read in conventional ways. It denied the system the satisfaction of knowing or owning the subject through recognition.

Punk style wasn’t trying to communicate. It wasn´t the self-expression in the traditional sense. It was confrontation. A provocation. A refusal to perform palatable identity. A mohawk tells you that someone is into the punk aesthetic, but it doesn´t tell you who they are, or what they want. It doesn´t offer a stable narrative. It disrupts the expected link between image and message. How it operated, socially and psychologically, was not about clear transmission. It was about interruption.

Dick Hebdige´s foundational text, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979), frames punk style as a form of semiotic sabotage. Punk reassembled the signs of bourgeois life - school uniforms, safety equipment, national iconography - and reversed their codes. a safety pin became a piercing. A Union Jack became a provocation. The schoolboy blazer…as if. These were tactical distortions - acts of defamilarization.

Angela McRobbie´s work brought this closer to the lived surface of subculture. She analyzed how punk made room for those excluded from dominant forms of self-expression through zines, DIY performances, and re-appropriated fashion. Her analysis emphasized punk´s role in building informal infrastructures that supported autonomy.

But punk style was not only about symbolic inversion. It was spatial and material. A mohawk was not just a hairstyle - it was a strategy of spatial defence. It carved out distance, made people look twice and feel uncomfortable. The jagged silhouette of punk was a way of altering how the body occupied space: on the bus, in the street, in the subway.

This visual language operated as a form of counter-conduct, in Foucault´s terms. It was not an appeal to a different politics - it was a disruption of the everyday protocols that organize bodies into acceptability. Punk did not confront dominant power with a clear alternative. It refused the process of normalisation itself. It made the managed surface of the social world visibly unstable. Punk style was not a performance of rebellion - it was a shield for subjectivity. It protected the space where identity could exist without being made productive. Refusing the very expectations of society and being objectified.

That refusal, however, was never purely aesthetic. The aesthetic was a threshold, not a foundation. The optics were only authentic when they emerged from an internal refusal. Punk style may have been the most visible aspect of the movement, but it was never the essence. One could adopt the symbols - wear the pins, spike the hair, tear the shirt - and still miss the refusal beneath it. Punk is not a uniform. Punk is a mindset.

Being the Subject of One´s Own Appearance (© picture source in the book: D. Parkinson, S. Rock, Chaos to Couture, P27 ©still life picture: Edie Lou)

Jordan: Embodiment Against Legibility

Nowhere was this “communicated” clearer for me than in the work of Vivienne Westwood and the presence of Pamela Rooke - Jordan. In early punk London, Jordan became a fixed point. Her appearance - engineered peroxide hair, sharp eye makeup, latex, mesh, and a transparent vinyl coat worn without layers. Her image was clear. She appeared without explanation, regardless of reaction. She didn´t seek validation. She moved through space effortlessly composed and self-curated.

That structure functioned. Beyond style. It altered how space behaved around her. She redefined rooms. Her appearance operated independently, with its own logic. She moved through the city as a self-authored figure, one who neither offered explanation nor absorbed projection. What she created was a visual condition in which identity could hold- without translation, without compromise, and without needing to resolve into something consumable.

Jordan did not argue her position - she held it. Day after day, she moved through public space, self-authored. She didn´t ask to be understood. She did not express punk, she operationalized it. What she enacted was a form of ontological autonomy: presence structured from within, maintained without appeal, and uninterested in resolution. She did not respond to the gaze or negotiate with public space. She authored the terms on which she appeared. It was not about rebellion alone. It is not about style. It is about the structure of the self - being the subject of one´s own appearance, behavior, and position, without adjusting them to meet legible norms. That is what Jordan held.

Westwood, McLaren & SEX

Vivienne Westwood approached fashion on similar terms. Working with Malcolm McLaren at SEX, she produced garments that were deliberately uncooperative: shirts printed with pornography and fastened with chicken bones, trousers deconstructed, vinyl and latex, silhouettes out of balance. Westwoods designs did not work within approved societal codes. They stripped fashion of its function as a sorting mechanism. It was beyond rebellious, it was structurally disruptive.

Punk had a sound and it had a silhouette. What was first? Your guess… But one thing is clear. Westwood and McLaren weren´t producing fashion or a new style, but just garments per se. They were constructing presence - something that holds space, carries force, and refuses to collapse into legibility. Whether it was Rotten´s disintegrating uniform, or the Dolls styled in iconography, the outcome was the same: a presence that didn´t collapse into a type.

What they created wasn´t just a style - it was a visual framework that captured the mindset already forming around it. They were systems of appearance built to hold a position - without explanation. Chrissie Hynde later said: “I don’t think punk would have happened without Malcolm and Vivienne…Something would have happened, but it wouldn´t have looked the way it did.” And the look kicked. They shaped a scene - without codifying it, explaining it, or making it comfortable. Their boutique on King´s Road did not sell a style, it sold confrontation. The garments on the racks weren´t expressions of taste or belonging alone. They were physical tension. SEX did not reflect punk. It preceded it. The look that emerged from that space didn´t illustrate an ideology. Just like Jordan, they made something visible that didn´t yet have a language.

Punk´s autonomy extended beyond appearance. It shaped how things were made, shared, and circulated. Records were pressed independently. Zines were stapled and Xeroxed in bedrooms. Gigs took place in squats, basements - wherever space could be claimed. What emerged was not only a subcultural economy. It was a structure of production and exchange built on immediacy, intent, and refusal. It was a refusal of dominant value systems. Punk sustained another logic - where self-expression did not need to conform to institutional formats to be valid. The work mattered because it made space for presence that could exist without explanation. It did not arise from ideology. It was raised from tension - from the friction of moving through systems that demand elegibility, and choosing not to comply.

It is about existential FREEDOM (©picture: Edie Lou)

Why It Still Holds

What the fashion industry, entertainment platforms, and branding culture absorbed was the surface grammar of punk: the silhouette, the typography, the visual cues of confrontation. These can be flatterned, repackaged, marketed, and sold. But what they can not reproduce - what resists simulation - is the structure of mindset behind it.

And why are we still fascinated by? Well…whether we admit or not, most of us feel the weight of being shaped and boxed - by school, social media, jobs, politics, expectations. We are trained to be understandable, productive, likable, compliant. Even our defiance is often absorbed back into the system as a performance - calculated, legible, sellable. (Oh… marketing, we love you so!) But punk touches something: the desire to be real without needing to perform. It gives us a glimpse of what it feels like to exist outside of expectation of society - outside the mainstream, outside the loop. It does not ask for permission.

Punk functions on a refusal to compromise the self in order to be legible. That is not something you wear. It is something you either live - or you don´t. It is not just the sound or the look, obviously. Your studded jacket won’t fix the deal. It is something more behind it. It makes room for identities that does not fit, for expressions that does not resolve, for truths that are not optimised for delivery. It is about existential FREEDOM. Living fully with honesty.

The system still rewards legibility, productivity, compliance, doesn´t it? If you don´t fit, you’re marginalized. If you can’t be explained, you’re ignored. The terms remain: adapt or lose. In that context, punk still functions - not as nostalgia, obviously, but as a healthy reaction to an unhealthy system. It was never just a rebellion for its sake. It was - and is - a structural refusal to be turned into an object. A refusal to submit to frameworks that flatten identity. A space for being real.

Punk was not dysfunction. It was sanity. And unless the system changes, it will keep being necessary. You can misunderstand it. You can reduce it. Use it. But you can´t strip it of what it holds. And we love it for that with lasting respect for those who built it.

“Punk was about succeeding without any skills except honesty. Honesty isn´t easy though. That´s where the art, unironically comes in.” (Richard Hell)

https://www.metmuseum.org/met-publications/punk-chaos-to-couture

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23172446-vivienne-westwood

https://www.erikclabaugh.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/181899847-Subculture.pdf

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-21168-5_1

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/14595.Please_Kill_Me

https://www.gettyimages.ch/fotos/jordan-mooney

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eizQ9l9Qu0A

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0850702/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZF-52Qo6zGE