Subculture: outside the frame

Before the art world called his work genius, Jean-Michel Basquiat was painting on walls, refrigerators, and scarps across downtown Manhattan - creating a visual language no institution could recognize, let alone control. His work was immediate, improvised, and unconcerned with recognition. It did not emerge from institutional validation, nor from market incentives. It came from a personal urgency to mark the world, to produce something that neither the existing art world nor the mainstream culture could account for. Most cultural movements begin this way: outside sanctioned spaces, through necessity rather than approval.

Subcultures, obviously, follow the same pattern. They are not just reactions to trends. They are deliberate constructions of identity and meaning, formed when dominant frameworks no longer serve. They emerge when institutions, markets, and mass systems cannot address the complexities of particular lives. Subcultures are rarely comfortable or stable. Subcultures don’t operate with institutional security. They demand commitment without guarantees - only the possibility of building a symbolic world that feels coherent to the people inside it. They seek legibility among those who understand. Participation often comes with social, professional, or economic risks, but also with the possiblity of building symbolic worlds that feel real and necessary.

Subcultures do not emerge by accident. They are built - in response to dominant systems that fail to account for certain identities, values, or aesthetics. They structure where mass culture flattens complexity. At the same time microcultures have become central to how culture circulates now. These are small, fluid groups that often form online, organized around shared aesthetics, references. or emotional tones. A meme, sound, a niche visual language, an inside joke - micro cultures are not built to last, and they rarely aim to. A TikTok mood, a Discord channel, a two-issue zine collective- they surface, shift, and dissolve - without warning. But while they exist, they offer real coherence and creative intensity - however temporary. And there are those, the countercultures. They move differently. They are built on refusal - of institutions, ideologies, and dominant norms - and often carry a political or activist intent. They are not defined by niche identity, but by the desire to dismantle or replace larger systems. In this article, the term subculture will be used broadly to include countercultures and micro cultures.

What links all three is the decision to build meaning on different terms. They are forms of authorship created in real time, often with limited resources and no safety net - but with clarity about what the dominant culture is not offering.

But how do these sub-/micro- and counter cultures continue to function as spaces for creating meaning, resistance, and identity construction? What is the history behind it? How is culture created now and in the future? And will subcultures always exist?

Will Subculture Always Exist? (© of the picture belongs to the rightful owner)

A story older than it seems

Subcultures are often perceived as a product of the 20th century, but the impulse to create alternative symbolic systems predates contemporary frames. Throughout history, individuals and groups have constructed parallel frameworks of meaning when prevailing structures failed to encompass their needs. In the early Christian era, communities formed clandestine networks of ritual and identity within the Roman Empire, offering a spiritual counter-narrative to imperial authority. Similarly, from the 12th century onward, Sufi orders in the Islamic world established mystical fraternities that provided alternative spiritual paths, distinct from formal religious institutions.

Medieval European artisan guilds functioned beyond economic associations; they were symbolic communities with their own rituals, codes, and languages, fostering a sense of identity and mutual support. Beyond economics, guilds offered social insurance, mutual defence, and a controlled system of belonging. They were self-contained cultural systems, build to create belongings where broader societal structures offered none.

In the 17th- and 18th- century France, salons emerged as independent sub-systems of cultural production. They were a response to their exclusions from official institutions. The Church, universities, and academies regulated intellectual life and access to power, leaving entire groups - particularly women - outside the structures of formal knowledge. Figures like Catherine de Rambouillet redefined conversation as a serious form of authorship, constructing spaces where style, language, intellectual dialogues, and influence were developed on their own terms. Madeleine de Scudéry expanded this approach, using dialogue as a tool to map social relationships with a complexity that anticipated later disciplines. Madame Geoffrin, among others, curated networks of philosophers, artists, and writers that shaped the intellectual landscape of the Enlightenment from the margins.

These salons operated with their own hierarchies, codes, and systems of legitimacy. They were not seeking entry into official culture; they were creating alternatives to it. What they produced was not simply conversation or wit, but an infrastructure of ideas, tastes, and alliances that moved independently of institutional control. In doing so, they established a model of cultural authorship built through private systems, selective circulation, and strategic refusal - an architecture that subcultures would later inherit.

By the 19th century, the salon gave way to a new figure: the dandy. Detached from labor, disinterested in production, and entirely absorbed in the construction of the self as art, the dandy transformed identity into a symbolic system. It was not just a lifestyle. It was aesthetic resistance - a refusal to participate in the moral and industrial codes of the time. The dandy did not just dress differently. He operated on a different timeline, a different logic of attention and value.

Oscar Wilde Did Not Conform to the Dominant Codes of Manhood

The Dandy

Beau Brummell - the pioneer of the dandy - with his minimalist elegance, redefined what it meant to be seen. By rejecting the ornamental excess of aristocratic fashion in favour of pared-down elegance, he transformed self-presentation into a form of intellectual and social authorship. Oscar Wilde expands that gesture into full theatricality, in both his writing and his public persona. Every gesture, every excess, every refusal to perform seriousness was intentional. In a culture built on legibility and control, Wilde chose to be unreadable. Victorian society saw style as superficial, feminine, unserious. Wilde flipped that - showing that aesthetic choices could be more radical than political statements. He used beauty, irony, and surface as tools of resistance. Wilde did not conform to the dominant codes of manhood - he did not perform stoicism, restraint, or heterosexual normatively. His self-presentation queered public life - not just in sexuality, but in structure itself. Of course, that refusal of masculine legibility made him especially threatening to a patriarchal system. He did built a system where language, style, irony, and posture carried weight - without needing institutional approval. His life was not just a performance, it was an early model of subcultural authorship.

Oscar Wilde marks a turning point in the structure of cultural resistance. Before him, symbolic communities were largely collective - producing meaning through shared codes, rituals, and internal hierarchies. Wilde introduced a second architecture: the individual self as a site of symbolic authorship. Through aesthetic construction, strategic illegibility, and surface coded as critique, he shows that identity could be designed deliberately, without needing the approval or recognition of dominant systems. Wilde did not necessarily abandon collective meaning. He was performing autonomy, wit, and refusal. After him, subcultural authorship could happen at two scales at once: through collective systems of belonging, and through individual acts of coded refusal. That fracture - between collective identity and aesthetic self-construction - defines much of what subculture, micro culture, and counterculture, would become in the century that followed.

The Twentieth Century: Subculture as Counter-Structure

If the dandy introduced self-styling as subversion, the twentieth century turned that impulse into a cultural engine. As modernity fractured identities, uprooted traditions, and accelerated time, subcultures became the places where people reassembled meaning. They were not just aesthetic experiments. They were counter-structures - parallel worlds built on resistance and refusal. The Symbolists in late-19th-century Paris laid early groundwork. Rebelling against realism and rationalism, they turned inward - towards mysticism, decay, eroticism, and the subconscious. Their influence flowed into the Dadaists, who emerged in the shadow of World War I in Zurich and rejected reason itself. For Dada, absurdity wasn´t decorative - it was a weapon. Meaninglessness became critique. They tore language apart not to destroy it, but to rebuild it under new rules. Deconstruction, pure.

From there, the Situationists - especially Guy Debord - took up the project, arguing that capitalist society had turned life into spectacle. Their answer was disruption. It was dérive, détournement - the hijacking of media -, and play to unmask the illusion. Subculture here became urban drift, visual sabotage, the subversion of meaning through humour and collapse. Their fingerprints are still visible on punk flyers, meme subcultures, and the aesthetic of collapse - torn graphics, photocopied textures, glitched images, layered chaos, anti-branding that circulates online today.

Billie Holiday

But subculture was not only unfolding in the cafés of Europe or the pages of avant-garde journals, of course. In the shadow of segregation, amid the systemic violence of American racism, a parallel movement was taking shape - rooted in Black aesthetics, sonic innovation, and the radical artistry of self-styling. The Cotton Club, one of Harlem´s most iconic venues, had started as Club Deluxe. Opened in 1920 by the heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and later taken over by the Prohibition-era gangster Owney Madden, who transformed it into a whites-only nightclub featuring Black performers. This racial paradox - Black creativity under white control - makes the Cotton Club an especially charged symbol: both a platform for groundbreaking artistry (Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Cab Calloway) and a space shaped by exclusion and exploitation, obviously. It was more than a music scene. It was a cultural system: style, poetics, politics, elegance, improvisation. Te Black Dandy emerged as a bold reclamation of visibility. Tailored Zoot-Suits, silk ties, walking sticks - this wasn´t just aesthetic. It was armor. A refusal to be unseen. Clothing became a strategy of presence. As historian Monica L. Miller writes in Slaves to Fashion, the Black Dandy aesthetic is about agency and subversion through the very act of being seen with intention.

This lineage reverberates forward- through the suits, funk, ballroom culture, hip hop, Afrofuturism. What begins in tailored resistance becomes a full spectrum of subcultural style. This logic doesn´t fade. It becomes foundational. The figure of the Black Dandy marked more than a visual shift. It signalled a turning point in how performance, identity, and cultural power were configured. From that moment forward, subcultural structures became tied to music - as a system of survival and self-definition. This formation did not begin with punk or hip hop, obviously; it begins with the blues. Out of the blues emerged soul, funk, and rock - each carrying not only sound, but the residue of historical struggle, coded resistance, and aesthetic control. I think we can say, that every major music subculture of the twentieth century builds from this foundation. What begins in blues as grief and endurance becomes, over time, a global architecture of style, refusal, and community.

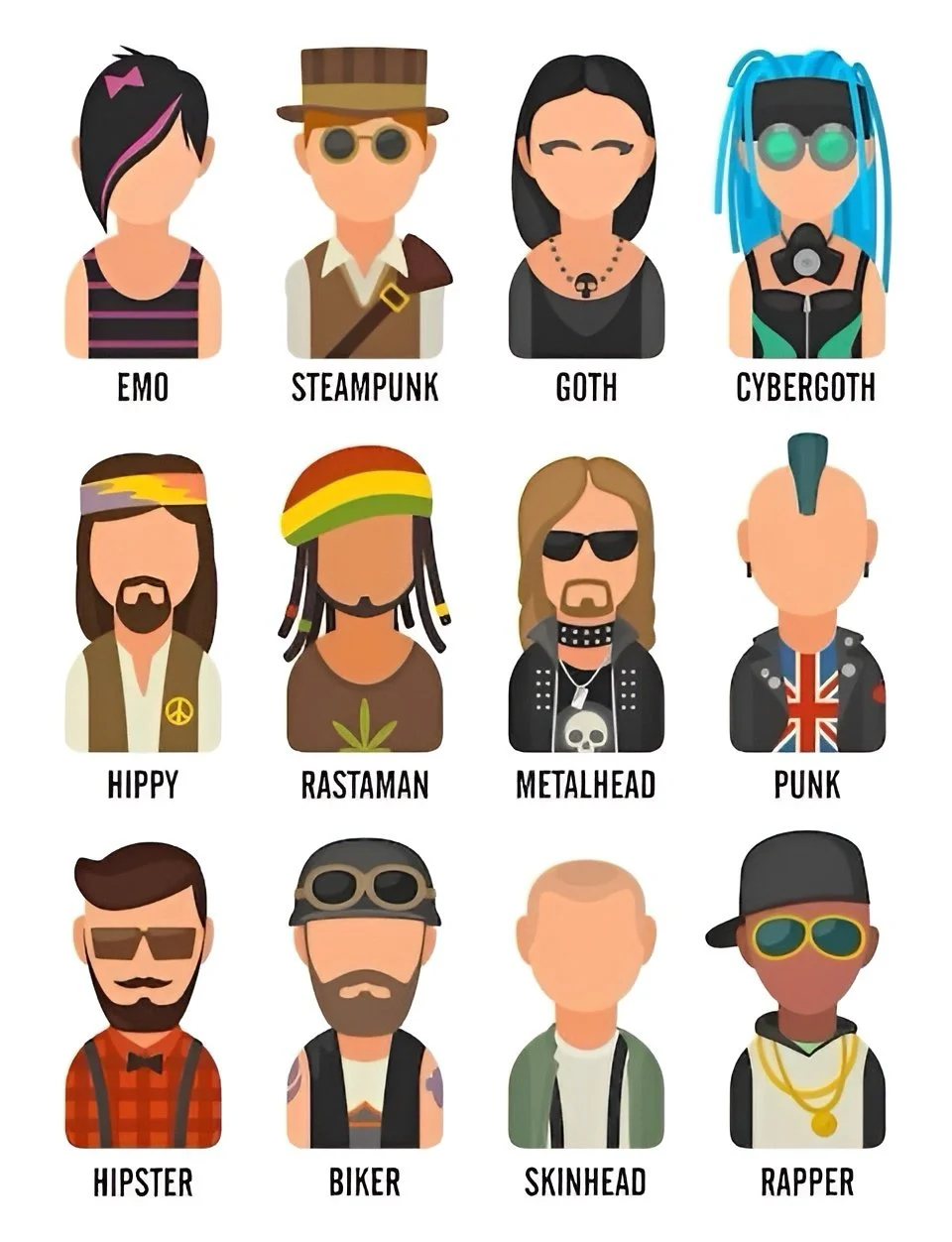

By the mid-twentieth century, subcultures had become full symbolic systems - built from music, style, and refusal. From the Teddy Boys in postwar Britain to the surf communities in California, youth movements turned aesthetics into structure. Punk, goth, hip hop each formed their own codes. visual, sonic, and social. Whether through distortion, rhythm, they offered alternative ways to be seen - and to belong - outside institutional visibility.

By the early 2000s, the structure of subculture shifted again - to digital space but the connection between music, visibility, and identity continued. Emo and scene culture became some of the first mass digital subcultures, shaped not just by bands but by MySpace profiles, image filters, typography, and mood. Style became pixelated, curated in HTML and song lyrics. Alongside them, micro.scenes like elctroclash, cyber-goth, and blog house blurred irony and sincerity. These groups often had no fixed geography - just hyperlinks, low-res photography, and fast-shifting codes. They anticipated what would come next: total digitization.

The formats changed, but the function endured. Subcultures remained a space for those who refused to exist merely as a response to society’s expectations - who insisted on shaping identity beyond reaction, on their own terms.

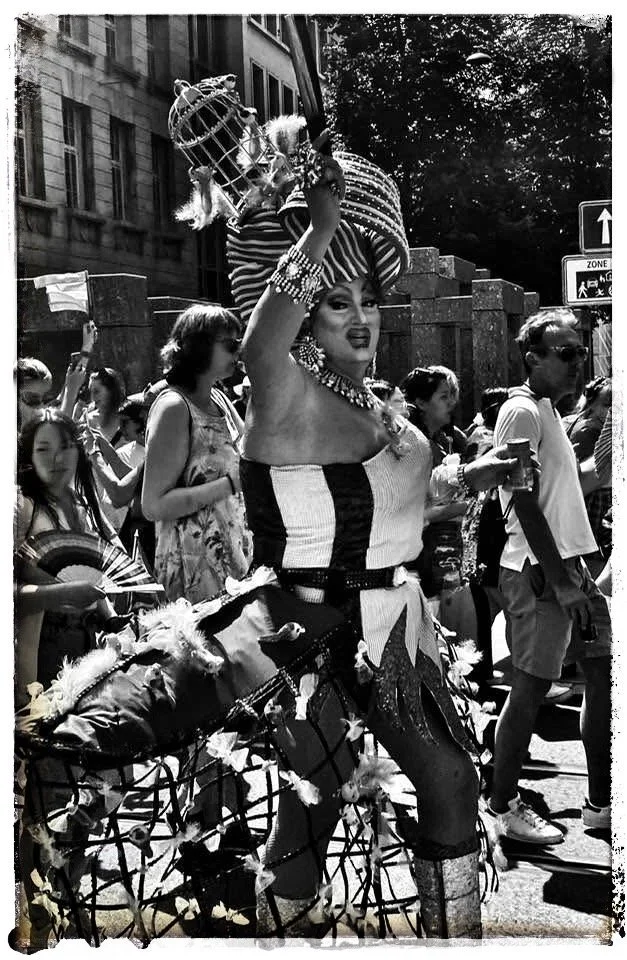

“Difference” Becomes Desirable Only When It Can be Contained, Stylized, and sold (© of the picture belongs to the rightful owner)

Eating the Other

Over the past several decades, aesthetic codes developed within subcultures have migrated steadily into the mainstream, often losing the specificity, resistance, or lived conditions that once defined them. Graffiti, once criminalised, now commands auctions. Punk fashion circulates through luxuryy brands. Hip hop´s visual grammar - shaped in underfunded neighbourhoods - serves as global branding material. What was once margin becomes motif. But what is behind it? Why is the mainstream first rejecting, then eating everything?

In Eating the Other, bell hooks writes with precision about how dominant culture consumes the aesthetics of marginalized communities - particularly Black culture - without acknowledging the histories, violence, and resistance that “produced” them. She describes how “difference” becomes desirable only when it can be contained, stylized, and sold. Cultural symbols are lifted, aestheticized, and detached from context. What was once political expression becomes surface. What once signalled struggle becomes design.

This process is rarely immediate. It begins with rejection. Subcultural forms - whether they emerge from Black, queer, working-class, or immigrant communities - are often met first with ridicule or fear. Too raw, too strange, too resistant. Dirty. But once the aesthetic proves useful - visually compelling, commercially viable, emotionally charged - the mainstream begins to absorb it. Not by understanding it though. But by extracting what can be used and discarding what cannot.

Behind all this is the recurring mechanism of cultural extraction: reject, reframe, commodity. The mainstream resits what it cannot immediately categorize. Subcultures are often first met with suspicion, mockery, or fear - seen as threats to order, taste, or normativity. But once the edge has been dulled - once risk is replaced by market potential - these same forms are recast as innovation. Their symbols are extracted, drained of context, and reintroduced as trend. It is not a misunderstanding. it is a process of cultural control.

The Logic of the Scene Is Flattened Into a Cheap Theater

Escape from Freedom

bell hook´s analysis remains essential because it names the asymmetry within that process. Appropriation is not simply an aesthetic exchange. It is about power - about who is allowed to take, who is expected to give, and whose meaning survives translation. When subcultural symbols are lifted from their context, what is lost is not just authorship but coherence. The logic of the scene - its rituals, hierarchies, references, affective economies - is flattened into a cheap theater. What was once identity becomes style. What was once belonging becomes branding.

This process is sustained by a mainstream psychology that privileges the familiar, the repeatable, the socially affirmed. Mainstream culture does not innovate; it follows. Its power lies in amplification, not invention. It seeks out what has already gained traction in the margins, then strips it of contradiction or complexity in order to make it broadly consumable. This is not simply passivity - just to be fair - it is a survival instinct. To align with the mainstream is to avoid risk. To follow is to be legible. To adopt what has already been accepted is, for many, easier than confronting the discomfort of the unfamiliar. Subcultures, like any other marginalized systems, are not for the weak. It requires courage.

And the structural weakness of the mainstream lies in its dependence on consensus. When a culture prioritises stability - alignment - over scrutiny, and familiarity over contradiction, it leaves itself vulnerable to political and ideological capture. The avoidance of complexity may feel like neutrality, but it is often a refusal to take responsibility for meaning. The mainstream is structurally passive. It is a system optimised for ease over responbisility. That makes it particularly susceptible to manipulation: by populism, commercial exploitation, or ideology. When comfort becomes the norm- and anything that disrupts consensus can be cast as a threat, rather than a warning.

Erich Fromm argues that modern individuals, especially in times of instability, often experience freedom not as empowerment but as anxiety. That anxiety makes them susceptible to authoritarian ideologies - not because they are inherently cruel, but because they crave certainty and direction. His central idea is that freedom is psychologically difficult, and when institutions do not help people navigate that difficulty, they may “escape” into obedience, nationalism, or mass ideology. Authoritarian ideologies, Fromm wrote, do not “seduce” the masses with terror alone. They succed because they relieve people of the anxiety of thinking for themselves. It is more convenient. In that sense, the danger of the mainstream is not its hostility to dissent, but its indifference to it. The comfort of alignment becomes more appealing than the responsibility of resistance.

Subcultures have never been designed for mass appeal. They emerge not form consensus, but from refusal - from the need to live and create beyond the limits set by dominant norms. For many, subculture is not a lifestyle decision - it is a condition. Skin, gender, class, displacement - these are not choices. They are lived realities. And they shape the codes people build to survive. The choice is not whether to belong to the mainstream, but whether you will disappear under its pressure - or create a structure that lets you remain visible and sane. And do not forget: visibility can be dangerous for those who do not conform and to persist in one’s identity under threat is an act of political courage.

Subcultures Will Not Disappear

Why Subcultures Will Not Disappear

Subcultures are not trends. They are responses to cultural pressure - forms of expression created when dominant systems fail to offer meaning, innovation, dignity, or space for difference. Subcultures exist because humans are fundamentally social, but never uniform. Wherever there is a dominant cultural narrative, there will be those who do not see themselves reflected in it -because of class, race, gender, taste, belief, desire, or lived experience. Subcultures form in the gap between the norm and the lived. They are not side effects of culture; they are a primary way that culture adapts to diversity and contradiction.

From a sociological perspective, subcultures are an expression of symbolic boundary-making. People create distinctions to signal identity, values, and belonging. When dominant institutions fail to offer meaning that feels honest or lovable, alternative systems emerge. Subcultures provide those systems: through language, dress, music, ritual, or aesthetic code. They give individuals ways to locate themselves socially and symbolically, especially when the mainstream does not. Psychologically, subcultures address core needs:for belonging, recognition, and coherence. Group affiliation helps individuals reduce uncertainty and construct stable self-concepts. They function as identity anchors in a fragmented world. That is why the aesthetic is never enough.

So…are subcultures dying out? No! Of course not. I just have said: we are wired to belong. But how does the future look like? Well, it will likely be more fragmented, more coded, and more deliberately invisible - as a survival tactic. As algorithmic systems continue to shape how culture is produced, distributed, and consumed, subcultures will likely pull in two direction at once.

On one hand, there will be hyper-specific, semi-closed scenes: private Discord servers, encrypted group chats, intive-only forums - spaces where coherence is built not through visibility, but through shared references, tone, and rhythm. At the same time offline communities are reemerging as deliberate spaces for cultural exchange that operate outside the demands of visibility and scale. These communities won´t seek scale. They will trade reach for depth. On the other hand, we will see aesthetic drift in plain sight. Fragments of subculture will continue to move rapidly through platforms - TikTok trends, meme formats, niche genres of music or fashion- but the speed of circulation will hollow them faster.

However, people will always need places to belong, to speak in their own code, to invent structures that do not flatten difference. Subculture will provide that. Humans have always formed micro-societies within larger ones. Whether through kinship, clan, guild, or secret society, we build smaller, diverse units within broader structures serve that same function: they are adaptive communities for survival. No one survives alone. We’re wired to belong. Without that, we fade…like dressing up in the dark.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/11052901-eating-the-other

https://www.museumofyouthculture.com/history-of-subculture/

https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/1339/Slaves-to-FashionBlack-Dandyism-and-the-Styling-of

https://www.erikclabaugh.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/181899847-Subculture.pdf

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25491.Escape_from_Freedom

https://www.iankelly.net/beaubrummell

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/512935.Beau_Brummell

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5294.Oscar_Wilde

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/310504.The_Republic_of_Letters

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249157751_The_Age_of_Conversation

https://search.worldcat.org/title/Guilds-of-the-Middle-Ages/oclc/16246421