when maison became a machine: how conglomerates industrialized luxury

Luxury once moved more in silence. It wasn’t just exclusive; it was elusive. It lived in ateliers and drawing rooms, not drop calendars and TikTok trends. For much of the 20th century, it was defined by its distance from mass culture - its slowness, its inaccessibility, its insistence on tradition and detail. Its presence evolved - from royal courts to 1980s haute couture - and of course that presence used to be coded, discreet, and socially gated, not constantly broadcast or algorithmically optimized.

The idea of a fashion house was once inseparable from the vision behind it. A house did not begin with a branding strategy. It began with a worldview. From Chanel’s radical shift of femininity and androgyny to Margiela’s anti-fashion deconstruction, these were not just brands - they were authored systems, slow-built over time, structured through repetition, refusal, and risk. Their identity wasn’t manufactured through external communication and branding strategies. It emerged from the internal structure of the work itself - the garments, the references, the process, the pace. Identity was a result of commitment. They did not just mirror culture and society. They challenged it.

The transformation of luxury fashion into a tightly managed global industry began in the late 1980s. and accelerated throughout the 1990s. The model was simple: consolidate heritage brands under centralized ownership, introduce professionalized management, and create long-term value by expanding into new product categories and global markets. This became the foundation for what we now recognize as the contemporary fashion conglomerate - a structure perfected by LVMH, Kering, and Richemont.

These groups did not invent luxury, obviously. What they did was standardize its production and distribution. They brought in financial oversight, vertical integration, and marketing systems borrowed from other sectors. Where once a creative director operated as the sovereign voice of the house, they were now one part of a larger operational mechanism. Under this model, a fashion house becomes a brand portfolio asset - one that must deliver not only cultural capital, but predictable financial performance.

At the heart of the conglomerate system is the concept of managed identity. Each brand is allowed to express its “heritage” and “codes”, but these are filtered through strategies designed for growth: expansion into leather goods, licensing deals, tiered pricing, and carefully segmented customer bases. A house may retain its historical references and iconic pieces, but its operations are aligned to match group objectives - profitability, reach, and brand synergy across regions.

Bernard Arnault acquired Boussac Saint-Frère, a struggling textile group that owned Dior (©Edie Lou)

From Designer Houses to Corporate Assets

The shift from autonomous fashion houses to conglomerate-managed brands did not happen over night. By the late 20th century, many of fashion’s most iconic houses were structurally vulnerable. The couture economy - once sustained by private clients, craftsmanship, and cultural prestige - had become economically unsustainable. Ready-to-wear offered commercial promise, but required capital, logistics, and scale that most independent designers could not access. At the same time, global demand for luxury was growing rapidly, driven by new consumer markets in Japan, the U.S., and eventually, China, and the Gulf states. Fashion had cultural value - but few houses had the infrastructure to translate that value into long-term viability. But what fashion lacked was a system that could deliver it.

That system arrived through consolidation. In 1984, a little-known French businessman named Bernard Arnault - later became le soup en cachemire - acquired Boussac Saint-Frère, a struggling textile group that owned Christian Dior. Three years later, he engineered the merger of Moët & Chandon, Hennessy, and Louis Vuitton, creating LVMH. The merger was presented as a luxury alliance, but its implications ran deeper. It marked the beginning of a new model: one in which cultural capital and financial capital would not only co-exist, but operate through each other.

Arnault himself was not a designer, nor did he emerge from fashion’s inner cultural sphere. His background was in engineering and real estate development - industries defined by scale, logistics, and control, rather than creative expression. When he entered the world of couture in the 1980s through the acquisition of the bankrupt Boussac group, he was met with skepticism. The fashion establishment, still guided by designer-led houses and creative authorship, viewed him as fundamentally misaligned with the domain he was entering. His entry into the industry was widely viewed as opportunistic, even inappropriate. Many in the Paris fashion establishment doubted that someone with a corporate restructuring mindset could understand, let alone preserve, the creative and cultural capital embedded in houses like Dior.

Arnault’s response was to professionalize the business of luxury while retaining its symbolic appeal. He installed rigorous financial controls, centralized operations, and invested in global expansion. But he also understood the necessity of maintaining the brand’s cultural identity, historical value and narratives. Rather than interfering directly in creative output, he curated top-notch talent - designers like Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, John Galliano at Dior, and later Virgil Abloom - placing them at the helm of legacy houses while anchoring them to strategic business goals.

Over the next three decades, Arnault expanded LVMH into a portfolio of more than 70 brands across fashion, jewelry, cosmetics, hospitality, and spirits. Labels such as Givenchy, Loewe, Celine, Fendi, Bulgari, and Tiffany & Co. were brought into the fold. By blending creative leadership with corporate infrastructure, Arnault built a model that has proven both culturally influential and economically resilient. Till now.

Today, LVMH is valued at over $400 billion, and Bernard Arnault is among the wealthiest individuals in the world. He succeeded in making luxury scalable. The houses he acquired became global sales machines - disciplined, consistent, and commercially optimized. What had once been difficult to replicate was now structured for growth. But that shift came with trade-offs, the full impact of which would only become clear over time.

Following LVMH’s model, other conglomerates emerged. Kering, founded by Francois Pinault and originally a retail holding company, reoriented itself in the early 2000s toward luxury, acquiring brands such as Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, and Alexander McQueen. The Swiss-based Richemont Group took a parallel path, though more focused on high-end jewelry and watches, with Cartier, Piaget, Jaeger- LeCoultre, and Van Cleef & Arpels, alongside fashion houses like Chloé and Alaia. Together, these three groups now dominate the global luxury market, defining not just its economics but its pace, tone, and distribution.

A commercial apparatus engineered for consistent visibility, and scale (©Edie Lou)

The Democratization Illusion

In the late 1900s, Bernard Arnault initiated a structural shift that would come to define the contemporary luxury industry. Where couture houses once operated as fragile, founder-led ateliers, Arnault applied the logic of conglomeration: injecting capital, professionalizing operations, and building vertically integrated infrastructures around brand equity. Luxury, under this model, ceased to be a boutique exercise in taste-making and was recast as a scalable business proposition. The maisons were no longer independent visions; once defined by symbolic authorship and cultural depth, were reconfigured as cold, efficient businesses - components in a commercial apparatus engineered for consistent visibility, and scale. By the 2000s, this system was fully operational. LVMH and its peers had refined a model of fashion-as-spectacle: high-volume, high-margin, and relentlessly visible. Advertising expanded beyond magazines and storefronts; it passed directly onto the consumer. A bag, a hoodie, a sandal - these were no longer garments but delivery systems. They were branded conduits for recognition. The wearer became the medium and delivery systems. Logos became mobile billboards, and consumers began paying for the privilege of doing the brand’s advertising for them.

To function at scale, however, identity had to be systematized. The distinctive codes of the houses - once forged slowly through creative evolution - were distilled into assets: logos, silhouettes, archival tropes, visual moods. These could be inherited by successive designers, ensuring coherence across seasons and campaigns regardless of authorship. What had once been the product of experimentation and misrecognition now became a reproducible language. Identity, rather than something lived and developed, was rendered into a fixed aesthetic protocol. The result was operational consistency, but at the expense of narrative depth.

This shift also fundamentally altered the role of the designer. No longer central auteurs with long arcs of development, creative directors became rotating figures in a tightly managed system. Their ask was not to maintain it. The frequent rotation of high-profile designers - Demna, Michele, Piccioli, Anderson - is not a symptom of instability; it is a strategic feature of the model. Designers function as brand refresh mechanisms. Visionary thinking is welcomed only to the extent that il aligns with commercial performance and quarterly goals. The house continues uninterrupted; the name on the label shifts with the market.

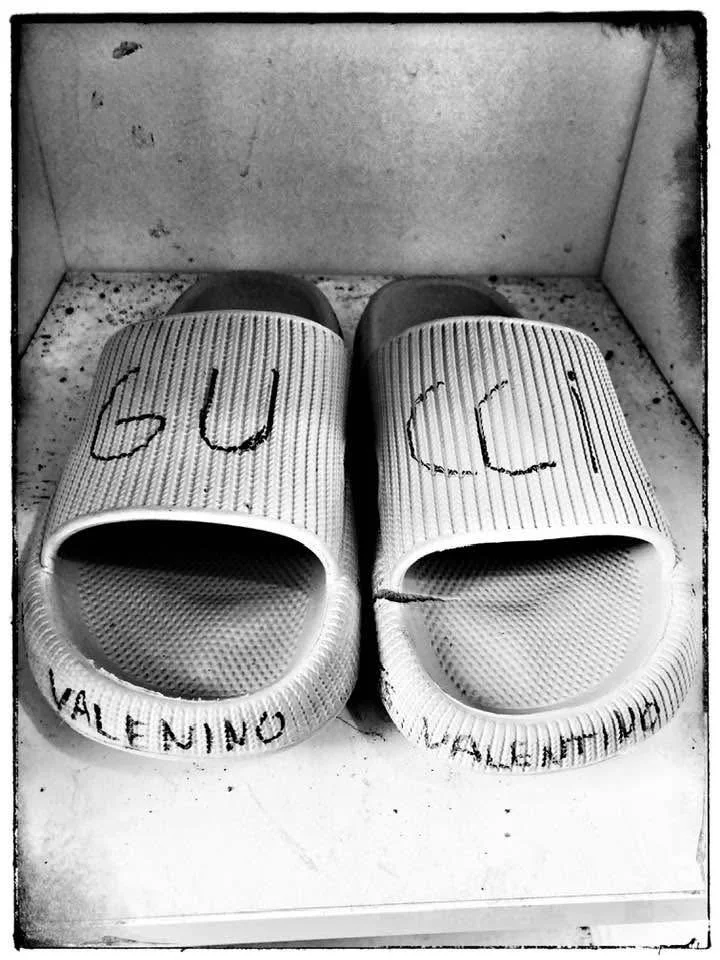

The consequence is a form of luxury that retains its outward prestige while losing much of its interior coherence. The garments remain meticulously crafted, the campaigns immersive, the brand storytelling confident. But the cultural memory embedded in these houses - once carried forward by idiosyncratic designers and shaped through decades of continuity - has been diluted. The product is no longer an outcome of slow and sustainable authorship but of responsive marketing. What endures today is not luxury, but performance. We can see them everywhere now - on sidewalks, at airports, in coffee lines. Luxury goods that once whispered now shout, they must compete for attention in an endless scroll. A sandal bearing the name Chloé no longer references a designer’s vision, or a legacy of craftsmanship - it functions as a surface, a status, prestige.

A sandal bearing the name Chloé no longer references a designer´s vision (©Edie Lou)

Economists like Luc Boltansky and Arnaud Esquire have written precisely about this shift: how luxury, once defined by craft and value, is now packaged and sold as a form of social status - a symbolic surplus attached to otherwise ordinary produced goods. The label, not the labor, is what matters. Everything circulates around the narratives and marketing strategies. The narrative matters that can be repeated, amplified, and circulated without limit. And for many consumers, luxury functions as validation. The newer, the louder, the more recognizable - the better. This is a performance-based model of consumption, rooted in external perception, not internal value. It mirrors the dynamics of fast fashion: regular novelty, high-volume marketing, seasonal obsolescence. The only difference is price.

This is also a consequence of scale. The larger the system becomes, the more it must simplify. As David Harvey notes in his theory of “flexible accumulation”, cultural production in late capitalism depends on rapid turnover and modularity - products must be made faster, distributed wider, and adapted to shifting trends. In luxury, that means sacrificing specificity for recognizability. Scarcity is no longer a material condition - it is a marketing strategy. The result is saturation. Aesthetic fatigue. What was once rare becomes ubiquitous, and what was once expressive becomes strategic. The Louis Vuitton logo, the Dior saddle bag, the Balenciaga sneaker - they are signifiers. They operate more like ad units than garments. And the more they circulate, the more they detach from the histories, methods, and identities that gave them weight.

Thomas Piketty, writing on the dynamics of capital, reminds us that in hyper-concentrated markets, wealth does not merely accumulate - it replicates. The same applies here: what LVMH and its peers have created is not cultural proliferation, but brand consolidation. The fashion landscape may seem diverse, but it is structured by a small number of firms, a limited number of distribution logics, and a homogenized visual vocabulary designed for mass decoding. And though it may still be expensive, it no longer feels rare and filled with history. It feels repeated and used.

Middle-class consumers today live in a status economy shaped by visual platforms (©Edie Lou)

What is Left to Build

What the conglomerates built is a functioning machine. It produces relevance, consistency, and profit. But what it also did - intentionally or not - was reorient luxury around value and visibility. Around circulation, not depth. And the model works. It delivers, of course. But it leaves no space for the actually premise: that fashion could be a form of authorship, value, identity, not just brand management.

Mainstream luxury - as defined by conglomerates like LVMH and Kering - has become over-optimized. Brands operate as systems of distribution and media, not as cultural authors. This leads automatically to rotating designers with no long-term authorship, products optimised for attention over depth, and a luxury market saturated with spectacle and repetition. The scalable - or mass-luxury - now runs on middle-class consumer psychology: identity insecurity, visible branding, and fast-status signaling. Conglomerates sell identity to those trying to buy it.

Middle-class consumers today live in a status economy shaped by visual platforms, income precocity, and social mobility anxiety. They are not simply buying clothes - they are buying visibility, recognition, and a proxy for confidence. Conglomerates understand this perfectly. Their business model isn’t built on aesthetic innovation, meaning, or craftsmanship; it is built on selling a sense of belonging to aspirational identities. That is why they invest more in image infrastructure (campaigns, celebrity seeding, social virality) than in actual design risk or the technical quality of how a garment is made. LVMH, Kering, and Richemont are not selling design, per se, they are selling identity kits - modular, high-margin products that can be slotted into someone’s visual performance of success.

So, the current system built by conglomerates like LVMH, Kering, and Richemont is highly effective from a business standpoint. These groups have transformed legacy fashion houses into profitable global machines. They’ve standardized operations, scaled production, and turned branding into media. But that system works by removing the very elements that once defined luxury: slow authorship, unique voice, material depth, and emotional resonance. When a designer becomes interchangeable, and when every product must be optimized for sell-through, what is left is a shell.

The future of luxury will be shaped by clarity of purpose and rigorous of execution (©Edie Lou)

The question now is whether we continue accepting a model that pushes product like fast fashion under the guise of luxury - or it is time to build something slower, smaller, and rooted again in meaning and lasting value?

The success of conglomerates like LVMH and Kering has created a paradox: the more dominant their model becomes, the more visible its limitations are. As mass luxury grows louder, faster, and more commercially repetitive, it inadvertently creates demand for its opposite - for fashion that moves slowly, feels personal, and carries integrity. This is not a rejection of luxury; it is a response to its industrialization. Customers who are no longer persuaded by logos or marketing strategies are turning towards smaller brands that offer clarity, intimacy, and a sense of identity. Ironically, the scale of the conglomerates is what makes this shift possible - by saturating the market with sameness, they open cultural space for differentiation. In making luxury a commodity, they’ve made room again for fashion to become a craft.

A new kind of luxury brand can be built by working differently. A sustainable alternative is not about returning to the past. It is about constructing a new framework that rebalances authorship, labor, and value. That begins with smaller production runs. They allow for quality control, supply chain traceability, and meaningful creative oversight. Slower timelines permit actual design development. Scarcity becomes a reflection of production integrity, not a tool of artificial demand. Transparency must be an operational logic. This includes crediting labor, disclosing costs, and refusing to outsource accountability. Transparency aligns incentives between maker and wearer - it closes the gap between price and value.

The future of luxury, I think, will be shaped by clarity of purpose and rigorous of execution. Brands that survive will not be the ones that chase attention, but those that construct systems capable of holding meaning over time. That means fewer drops, fewer compromises, and more discipline and ambition to make garments that are responsibly produced, transparently made, and built to last. The brands that will matter won’t compete on noise - they will earn trust through coherence and care. They will treat sustainability not as a trend but as infrastructure. Like a Seth Godin approach to fashion, these brands won’t chase everyone - they will speak directly to those who already understand. And they will build something lasting: not just a product line, but a system of values that can hold over time.

https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Enrichment%3A+A+Critique+of+Commodities-p-9781509528745

https://www.thefashionlaw.com/lvmh-a-timeline-behind-the-building-of-a-conglomerate/

https://www.ceotodaymagazine.com/2024/09/bernard-arnault-the-inspirational-success-story-of-lvmh/

https://www.galeriedior.com/en/history

https://www.whowhatwear.com/fashion/gen-z-small-fashion-brands

https://maisonshift.ch/Maison-Shift

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/80336.Distinction

https://www.thecollector.com/what-is-pierre-bourdieus-theory-of-taste/

https://web.stanford.edu/class/sts175/NewFiles/Harvey,%20Post-Fordism.pdf

https://files.libcom.org/files/David%20Harvey%20-%20The%20Condition%20of%20Postmodernity.pdf