avant-garde in fashion: when radical becomes a soft routine

Avant-garde is the beauty of the raw: the deliberate disruption of convention to reveal grace within what is fractured, discarded, or unseen. It is the transformation of exclusion into dignity, and imperfection into a new form of truth. (Edie Lou)

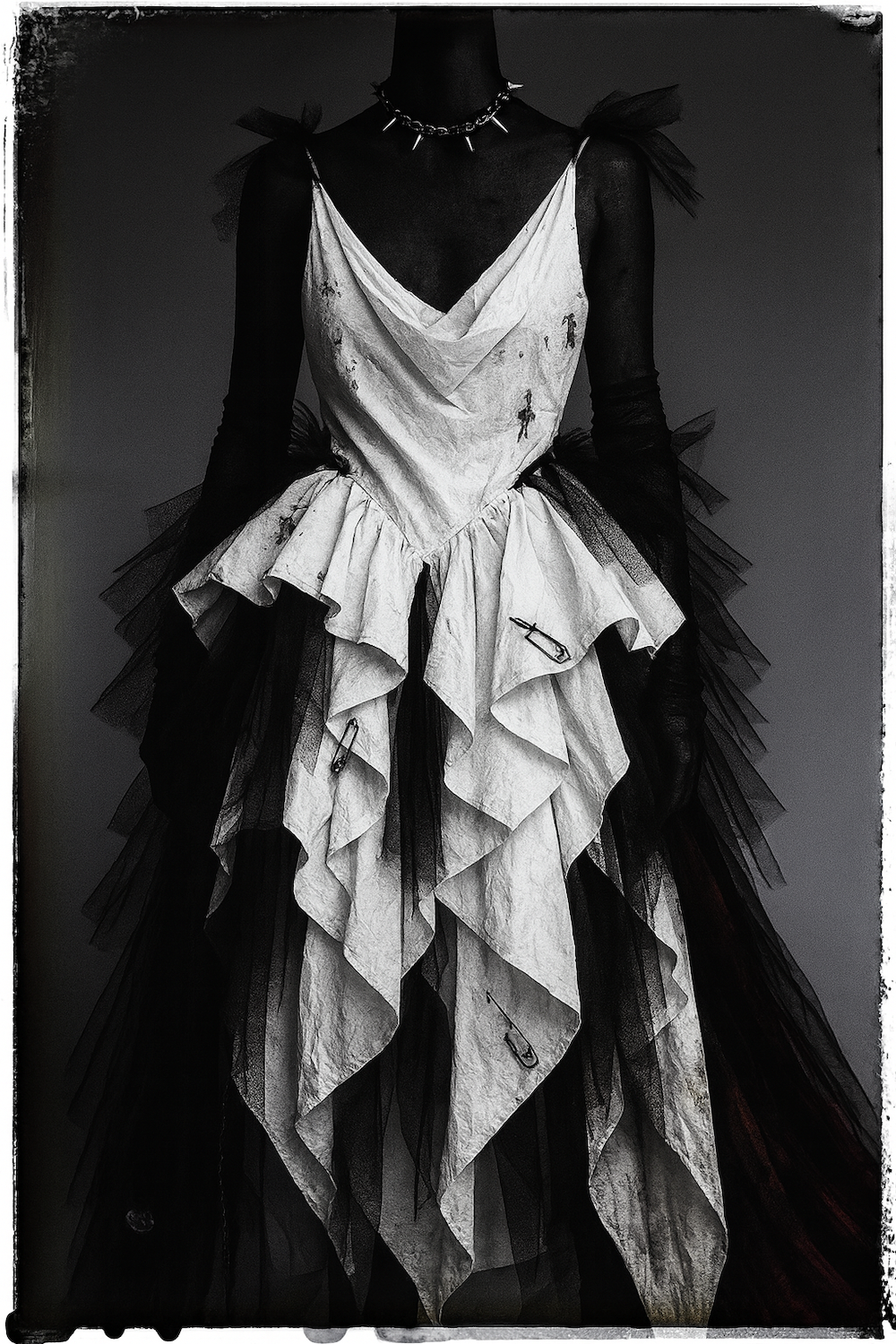

Avant-garde in fashion once meant danger. It meant garments that unsettled social norms, ruptured traditions, and redefined beauty itself. The beauty of the ugly, of the raw, unknown, unfinished. From Elsa Schiaparelli’s surrealist collaborations to Rei Kawakubo’s deconstructions of the body, the avant-garde was not a style - it was a stance. Born in the 19th century as an artistic vanguard - the “advance guard” challenging bourgeois taste - it thrived on provocation, rupture, and scandal. From Dada’s manifestos to punk’s safety pins, from Elsa Schiaparelli’s surrealist gowns to Martin Margiela’s deconstructed jackets, its force lay in destabilizing norms, taking what society considered stable and exposing their fragility.

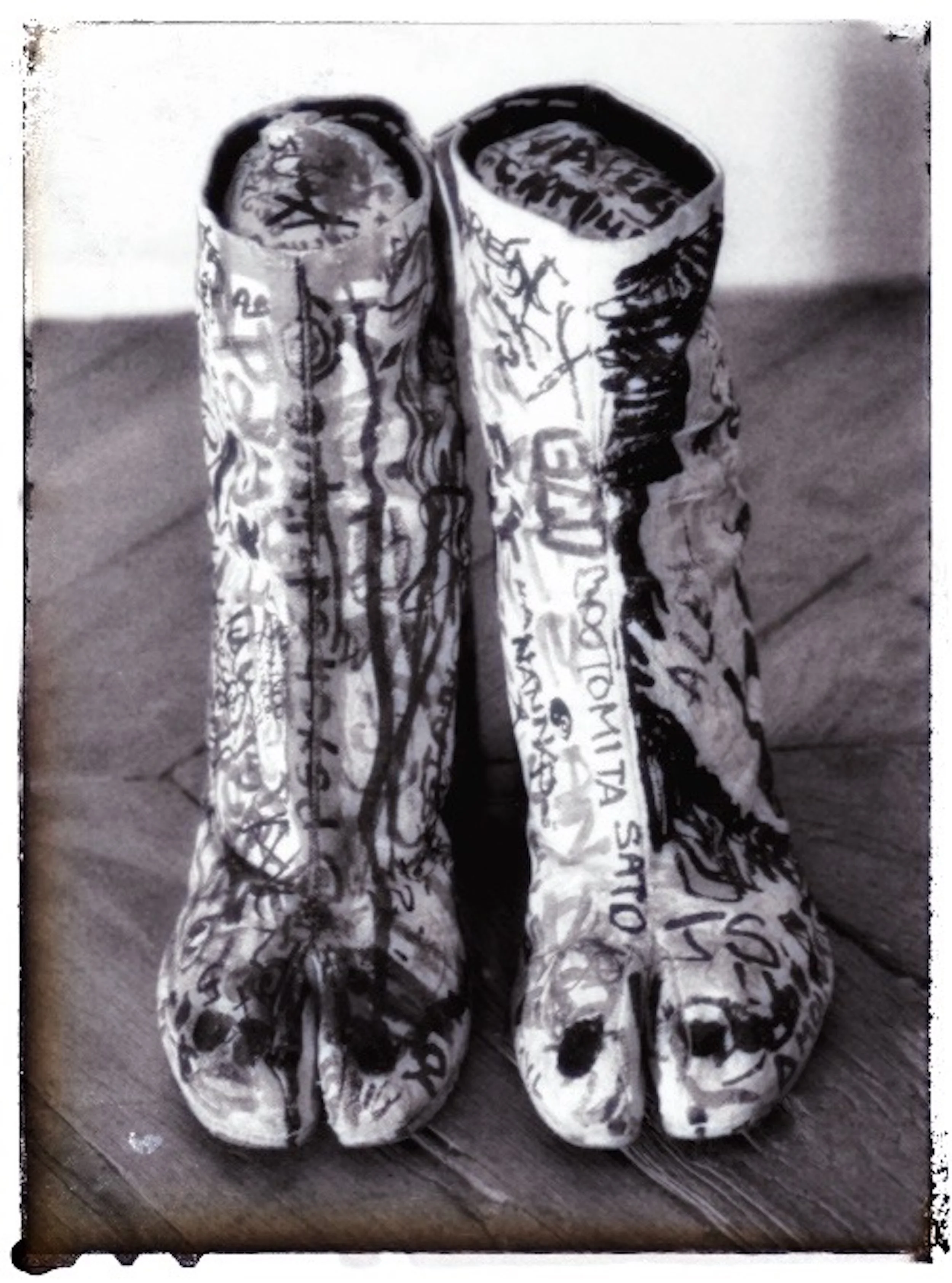

Yet in the 21st century, the gestures that were once shocking, radical, or disruptive (tearing apart a dress, putting men in skirts, staging chaos on the runway) are no longer threatening to the system. They’ve been absorbed into mainstream culture - recycled as style, sold as luxury, and turned into content for Instagram or TikTok. What was once radical has become archive; what was once shocked has been turned into marketing. Margiela’s Tabi boots, once a scandal - fashion press at the time often dismissed it as ugly or perverse, grotesque and hoof-like - are now bestsellers. Punk, once a howl against the establishment, has had many of its visual codes absorbed into commercial fashion. Rei Kawakubo’s lumps and bumps (Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body) are no longer shocking. Derided in the 1990s as grotesque - they are now enshrined in museum retrospectives and recycled as social media nostalgia. What was once scandalous has been canonized, its subversive charge diffused into heritage.

This raises a fundamental question: is the avant-garde dead, or has its battlefield simply shifted? If earlier avant-gardes worked by breaking silhouettes, shocking taste, or scandalizing ritual, today the dominant order must be different. Its terrain must be shifted. When aesthetic shock was new, it destabilized bourgeois taste; now, shock itself is commodified, sold back as nostalgia or conventionalism. But the necessity of an avant-garde remains - every age requires a force that resists its dominant logic. But the form must evolve. Today, the urgency is not about tearing hems or deconstructing silhouettes - we can get all this at H&M - that is too easy to absorb.

The avant-garde has always measured itself against the dominant order, unsettling what was taken as conventional or known. Obviously, it cannot repeat its 20th-century strategies of shocking silhouettes, scandalous performances, or anti-fashion gestures. Those elements and tactics have been absorbed into the mainstream. For the avant-garde to exist today, it must identify what our society most wants to conceal or hide and strike precisely there. Its survival depends on shifting its ground. The paradox is that the avant-garden is never a fixed thing. The moment it settles into a recognizable form, it ceases to be avant-garde and becomes history, citation, or commodity. When Dadaists tore apart language, or punk tore apart respectability, they were targeting what their own societies considered untouchable. So, if it shifts its ground, it remains avant-garde, precisely because it keeps faith with its essence: challenging the unchallengeable. If it repeats its old tropes, it ceases to be avant-garde, even if it still looks like it.

Gustave Courbet - The Trout “made while in chains”. Painted in exile in Switzerland (© of the photograph of the painting ©Edie Lou)

The Historical Avant-Garde: Shock as Weapon

The origins of the avant-garde lie in the 19th century, when the term was borrowed from military vocabulary to describe artists as a “vanguard” for society. In the French military, avant-garde literally meant the “advanced guard” or “vanguard” - the soldiers who moved ahead of the main army to explore terrain, encounter the enemy first, and clear the way. Around 1835, the thinker Henri de Saint-Simon borrowed the term for art and politics. He wrote that in modern society, it was the artists who should serve as the avant-garde, leading progress much like the military vanguard leads an army. Saint-Simon imagined art as a political force, a tool to guide collective consciousness and challenge entrenched hierarchies.

When Saint-Simon reframed avant-garde for art, he was positioning artists as agents of risk, obviously. To move “ahead of the army” meant entering uncharted terrain, facing hostility first, and bearing the uncertainty of whether society would follow. In the 19th century, stepping outside accepted norms was not just a matter of taste but of political and moral order. Artists who broke with convention could face censorship, exile, imprisonment, or even violent repression. This was a radical re-framing: instead of art serving the church or the aristocracy (as it had for centuries), the avant-garde was now positioned as a force of social transformation. The idea was that artists could anticipate the future, disrupt tradition, and inspire political change - not simply decorate existing power.

From this moment, avant-garde was not just a style, but a mission: to intervene in the structures of culture and power. By mid-century, this mission took aesthetic form. French Realists like Gustave Courbet scandalized bourgeois audiences by painting laborers and stone breakers on a monumental scale once reserved for kings and saints. In 1871, Courbet supported dismantling Napoleon’s Vendome Column, denouncing it as a symbol of war and tyranny. After the Commune’s defeat, he was blamed, imprisoned, and fined beyond his means, forcing him into exile. A reminder that the avant-garde once risked not just scandal, but freedom and survival. The same holds true today in authoritarian states where artists and writers still risk surveillance, censorship, or worse, when they dare to think differently. The avant-garde, in its truest sense, has always carried that danger.

However, art began to provoke rather than affirm, unsettling polite society by showing it what it wished to ignore: dirt, labor, sexuality, the crowd. This lineage carried directly into the early 20th century, when Futurists, Dadaists, and Surrealists escalated provocation into outright assault. They rejected the idea of art as refinement or ornament. Instead, they treated provocation itself as a tool - a way to strip conventions of their authority and expose the constructed nature of cultural norms. For the Futurists, this meant glorifying speed, machinery, and rupture with the past. For Dada, it meant mocking reason and order through nonsense and collage. For the Surrealists, it meant unveiling the irrational beneath the surface of everyday.

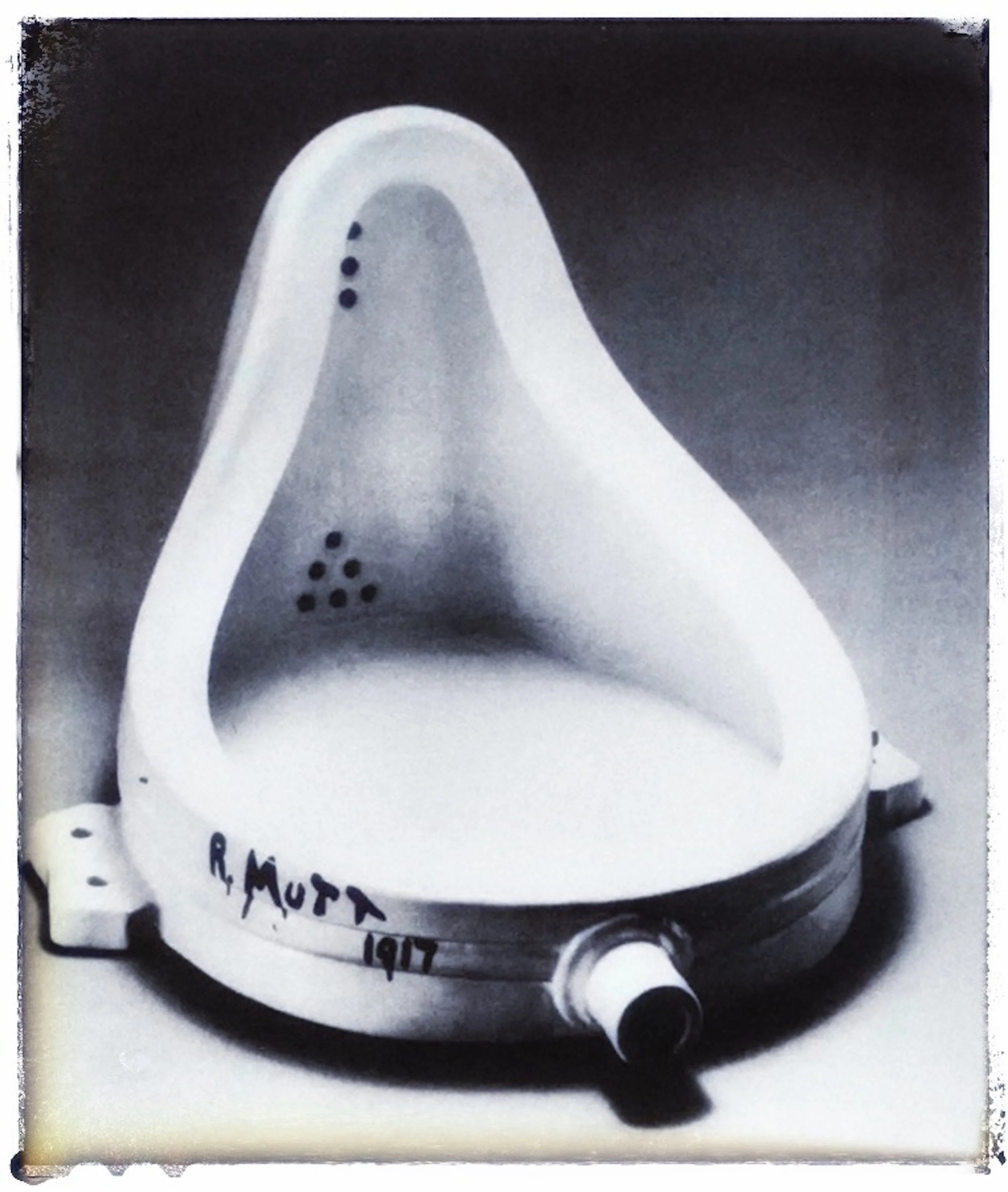

Marcel Duchamp - Fountain 1917 (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

In all cases, shock functioned as both aesthetic strategy and political gesture. To confront the audience with noise, fragmentation, or dream imagery was to challenge not just taste but also the social order that taste helped to maintain. In the early 20th century, “taste”, just like in the 19th century, was tied to morality, class, and authority. What was considered “good taste” reinforced the existing social order: bourgeois respectability, religious norms, and the performance of political stability. When avant-garde artists and writers introduced shock - noise in Futurist manifestos, fragmentation in Cubist painting, absurdity in Dada, dream imagery in Surrealism - they weren’t only breaking artistic rules. They were unsettling the values and hierarchies that those rules upheld. So, shock wasn’t superficial - it exposed what society called “order” or “good taste” as arbitrary, constructed, and vulnerable. In that sense, avant-garde aesthetics were inseparable from political critique.

In all cases, shock functioned as both aesthetic strategy and political gesture. To confront the audience with noise, fragmentation, or dream imagery was to challenge not just taste but also the social order that taste helped to maintain. When Tristan Tzara read absurdist poetry or Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal as art, they staged attacks on the very categories that structured bourgeois culture. This antagonism carried over into fashion as the century progressed. In the interwar years, Elsa Schiaparelli collaborated with Surrealist artists like Salvador Dali, and Jean Cocteau, translating their visual dislocations into garments. A shoe became a hat, a lobster appeared on a gown, a seam run deliberately off-kilter. These were not just whimsical flourishes: they unsettled the codes of elegance, mocking the stability of fashion itself. Fashion, like art itself, became a site where disruption could be tangible - enacted in everyday life. So when avant-garde strategies entered fashion, they worked semiotically, they disrupted the codes of meaning that defined social order. Elegance signified stability, gender codes signified hierarchy, and when those were mocked or inverted, it destabilized the symbolic order itself.

Evening Coat by Elsa Schiaparelli and Jean Cocteau, 1937 (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

From Disruption to Heritage: The Groysian Cycle

Boris Groys has argued that the avant-garde contains within it a paradox: the very act of disruption secures its own absorption. What is shocking today becomes tomorrow’s archive, museum piece, or marketable style. The avant-garde, in this sense, is never outside history but always in the process of being historicized. Its gestures of defiance are preserved, catalogued, and ultimately neutralized, transforming rebellion into heritage. The cycle is unavoidable: shock generates attention, attention produces preservation, and preservation erases danger. In other words, once something captures attention, institutions (press, museums, brands, collectors) step in to document, archive, and frame it. Once a disruptive gesture is preserved, its shock loses potency. What was once threatening is transformed into heritage, a museum piece, or a brand’s “icon”.

Punk offers one of the clearest illustrations in the 20th century. In the mid 1970’s, it was genuinely antagonistic: ripped clothing, safety pins, and DIY graphics embodied defiance of class hierarchy and political complacency. These gestures unsettled not only fashion but also social norms, communicating alienation and rage through visible acts of defiance. It was a weaponized sign. It emerged almost simultaneously in New York and London, but from very different conditions.

In New York, punk grow out of a bankrupt city abandoned buildings, and an artistic underground concentrated in places like CBGB’s. It came out of a collapsing urban-environment but also out of a thriving artistic underground. It was less about direct class confrontation than about DIY independence. The clothes were raw because the scene was raw: it was honest and unapologetically itself. Thrift-store finds, ripped jeans, leather jackets. They weren’t costumes or shallow style, like mostly today, they were what you had when you lived outside the mainstream economy. Your identity. And that material poverty turned into symbolic resistance. Anti-glamour was born out of necessity and intent, a semiotic rejection of mainstream values.

In London, punk was different. The social anger was more on focus. Youth unemployment in the mid 1970-s reached historic highs, while austerity and class divisions deepened. Punk here wasn’t just about dressing down - it was about weaponizing appearance. Westwood and McLaren amplified what working-class youth were already feeling, turning safety pins, chicken bones, ripped shirts, and straight forward slogans into provocations aimed at the monarchy, consumerism, and political complacency. In New York, punk grew out of an avant-garde milieu shaped by Warhol’s Factory, experimental music, and downtown counterculture, making it feel like an extension of artistic innovation. In London, by contrast, punk erupted against entrenched conservatism, rigid class structures, and industrial decline, its violence read as social collapse rather than just style. The result was one movement with two faces: evolutionary in New York, confrontational in London.

However, even punk, once raw confrontation, has been softened by time - its defiance transformed into heritage, its danger rebranded as style. Partly. Underground scenes persist and, in some political contexts, punk survives. The 1980s avant-garde in fashion carried forward punk’s refusal of convention but translated it into the language of high design. Rei Kawakubo’s work for Comme des Garçons in the 1980s and 1990’s followed a similar trajectory. Her1981 Paris debut with Comme des Garçons, often remembered under the label “Destroy”, scandalized critics. Reviewers described the collection as “ragged”, “post-atomic”, and “apocalyptic”. The black asymmetrical deconstructed garments with holes, loose threads, and distressed textures were interpreted in the West as a deliberate attack on established codes of luxury and beauty.

However, even punk, once raw confrontation, has been softened by time - its defiance transformed into heritage, its danger rebranded as style (© Edie Lou)

Rei and Martin

Her deconstructed silhouettes, dubbed “Hiroshima chic” by Western critics, scandalized conventions of beauty and form, redefining the body as asymmetrical, wounded, or grotesque. More than a decade later, her Spring/Summer collection was called “Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body” or nicknamed “Lumps and Bumps”. Instead of clothes that slim, elongate, or “flatter”, she built bulbous pads into knitwear, creating awkward protrusions at the hips, shoulders, and back. This made the body appear asymmetrical, deformed, or alien - a radical departure from fashion’s pursuit of proportion and elegance, what was still the main language in the 1990’s’ fashion. These gestures once generated outrage, precisely because they unsettled fashion’s deepest. codes of elegance and beauty. Yet today, Kawakubo’s most radical collections are housed in major museum retrospectives, their images endlessly recirculated on digital platforms.

Martin Margiela’s debut in Paris, Spring/Summer 1989, crystallized - just as Kawakubo - the avant-garde’s disruptive potential in fashion. Staged in a derelict playground in the 20th arrondissement, the show rejected the spectacle of Parisian luxury. Neighborhood children were invited as the audience, chalk drawings replaced marble floors, and models walked on makeshift planks. The setting dismantled hierarchy: fashion was not performed for elites but staged amidst ordinary life. The clothes themselves extended this gesture. Linings were worn outside, seams deliberately exposed, garments patched together from scarves or industrial textiles.

This aesthetic of deconstruction undermined fashion’s promise of polish and perfection, making visible the labor and fragility hidden within garments. At its center were the now-iconic Tabi boots, their split-toe silhouette referencing traditional Japanese footwear but shocking Paris with what critics called a “monstrous” violation of elegance. The shoe fractured one of fashion’s most stable signifiers - the perfect fitted shoe - and turned it into an alien form that unsettled both taste and identity. The scandal was immediate: some critics dismissed the work as vulgar or amateurish, others read it as a deliberate affront to Paris fashion’s authority. Yet this rupture was precisely the point. Margiela’s Tabi boots and deconstructed clothes exposed what fashion typically conceals unsettling the polished illusions on which luxury depended. They announced a new avant-garde vocabulary that reframed imperfection as a critique of the system itself. They announced a new avant-garde vocabulary that would define the 1990’s and Y2K.

But the trajectory followed a similar cycle. What was defined as grotesque or perverse in 1980’s has since been canonized. Today, Tabi boots are cult items, reissued seasonally, collected in museums, and recirculated again … endlessly on digital platforms. Margiela’s and Kawakubo’s debut exemplifies Boris Groys’s argument: the avant-garde is always caught in paradox. It aims to disrupt norms by producing shock, but once the shock gains attention, institutions archive or preserve it and so the act of preservation neutralizes the danger and makes it legible for the mainstream. So, the avant-garde “destroys itself by succeeding”: its rebellion turns into cultural capital.

Punk complicates Groy’s model a little bit because it is not only an aesthetic strategy but also lived counterculture. Punk was not just clothes - it was and is music, squatting, zines, underground networks, DIY economies. Even if ripped jackets end up in museums, at the Met Gala or on the runway, the subculture itself can continue outside of the system and institutions. Punk refuses legibility. It is an attitude and identity that cannot be institutionalized. Punk, being an identity and not only a style, sustains resistance outside institutions, which explains why it still functions as antagonism in certain spaces today. It always re-emerges whenever society produces conditions of alienation, exclusion, or … rage. Punk might be the only avant-garde that remains avant-garde.

Both Kawakubo and Margiela revealed fashion’s codes as contingent rather than natural, exposing seams, reshaping bodies, and unsettling conventions of elegance. Yet their critiques unfolded inside the very system they sought to disturb: Paris runways, luxury houses, global retail. They dismantled its surface while inhabiting its structure. In Groys’s terms, this ensured their absorption. What was once derided as grotesque, monstrous or perverse, transformed into heritage.

Rei Kawakubo - Destroy Collection (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

The Difficulty of Fashion’s Avant-Garde

Fashion has always struggled to sustain an avant-garde. Unlike punk or other subcultures, it is tethered to commerce and wearability. A garment cannot remain a provocation locked in a studio; it must circulate, be produced, and enter the cycle of use and visibility. This immediacy accelerates what Boris Groys described: the moment a gesture gains attention, it begins to be absorbed. A scandal on the runway becomes a collectible in a boutique, then a relic in a museum. Fashion’s model makes its avant-garde unusually fragile.

This fragility raises a sharper question: what forms of resistance can avoid being neutralized? Pure aesthetic disruption - silhouettes distorted, seams exposed, bodies exaggerated - no longer carries the same destabilizing force. Such strategies are quickly assimilated into the luxury system or endlessly replicated online. In a culture trained to metabolize novelty, shock is not subversive but expected. To function as avant-garde today, fashion must shift its ground: from style to structure, from surface to system. To gain a voice. The practices that fail are instructive. Instagram spectacles, nostalgic revivals of punk or deconstruction, or exaggerated silhouettes framed for vitality are not avant-garde. They mimic rebellion while feeding the very platforms and markets that thrive on acceleration.

Their legibility is precisely the problem: what can be easily read as “radical” can be just as easily commodified. These gestures recycle the grammar of provocation without disturbing the order that makes provocation profitable. And once a gesture arrives via television, reality shows, or other mainstream media, its approval is already guaranteed: it entertains, but it does not resist. Avant-garde cannot be pre-packaged for mass recognition; the moment it is sanctioned, it ceases to be disruptive. Instead of questioning the system, it entertains it. It is made to be easily digestible. But avant-garde, by definition, resists easy consumption.

And let’s face this: every garment must be worn, displayed, and socially decoded. This immediate visibility accelerates the process of interpretation: what appears on the runway can scandalize one season and circulate as street style the next or the other way around. The runway itself is not a marginal space but an institution, no less codified than television or other mainstream platforms. Its purpose is visibility. This means that even the most disruptive gestures arrive already staged for recognition, primed to be translated into spectacle, or market product. It is digestible and safe. The body ensures legibility, and the stage ensures circulation - together they transform provocation into fashionability.

Compounding this is fashion’s dependence on renewal. The industry is organized around seasonal cycles that demand perpetual novelty, which makes rebellion especially difficult to sustain. A radical silhouette or concept might destabilize conventions, but within months it risks being replicated, commodified, or archived. In this churn, the avant-garde becomes not an external challenge to the system, but its engine: disruption becomes predictable fuel for the fashion machine … then it stops being avant-garde. It becomes a marketing device, feeding campaigns, trend cycles, and the promise of “the new”. True refusals - delay, silence, withdrawal - pose a deeper challenge, yet they are nearly impossible to sustain in a system that punishes absence and rewards acceleration.

Fashion’s double bind of aspiration further complicates its avant-garde potential. Even when designers seek to critique consumerism, exclusivity, or glamour, they do so within a field defined by desire. A garment, however antagonistic, still promises allure, belonging, or distinctions. The risk is that resistance becomes another layer of aspiration: rebellion is bought, defiance is worn, system critique is consumed as style. Fashion’s status as both sign and commodity ensures that even its most radical gestures remain caught in the circuits of consumption.

Finally, fashion’s avant-garde is uniquely vulnerable to rapid capitalization. Because garments are reproducible and markets crave novelty, disruption is quickly absorbed into commerce. Punk aesthetics moved from underground communities to department stores within a decade; Kawakubo’s “Hiroshima chic” and Margiela’s deconstruction are now housed in museums and cited as heritage luxury. What once provoked scandal becomes codified, reissued, and archived. In fashion, no disruption remains untouched for long: the very mechanisms that grant it visibility also prepare its indifference. This is why fashion’s “avant-garde” so often becomes conservative - its challenges are consumed as quickly as they are conceived.

But if avant-garde remains only about shocking appearances, it will always be absorbed, it will navigate on the surface; to endure, it must create forms of resistance that the system can’t immediately turn into style or content. And why does the avant-garde matter at all? Well, because it preserves a space for dissent, imagination, and alternative futures in culture. If everything is absorbed into the mainstream - whether it’s politics, art, or fashion - then society risks losing its ability to question itself. Avant-garde movements have historically been the ones to reveal hidden violence (like war propaganda in Dada), expose hypocrisies (punk against class and monarchy), or propose new relations between humans and the world (feminist and ecological art). Without an avant-garde, culture becomes purely affirmative: it reproduces what already exists instead of showing what hasn’t yet been normalized. The avant-garde is not just about aesthetics, it is about human survival as political beings. It keeps culture from collapsing into obedience, speaks against political injustice, exposes it, and refuses its normalization, and insists on the dignity of the self by refusing to let individuals be reduced to passive consumers of dominant culture or political propaganda. It creates forms that resist domination and allow space for freedom.

Martin Margiel - Tabi Shoes, 1989 (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

The Limits of Avant-Garde in Affluent Societies

Talking about freedom, there is another aspect that needs to be considered today if we speak about the avant-garde. Let’s face this: the richer the country, the less space there seems to be. The more people agree on the system, the less they tolerate what unsettles it. In societies where people feel safe, materially comfortable, and largely supported by institutions, the perceived need for radical change weakens. Avant-garde movements thrive when people feel the system is brittle, unjust, or collapsing. But when life feels secure, even if problems exist underneath (such as ecological crisis, inequality, surveillance), people inside the bubble of comfort don’t sense the urgency to challenge it. Comfort shields the people from perceiving the fractures - making them less tolerant of disruption, because disruption feels unnecessary or even threatening.

Herbert Marcuse offered one of the sharpest diagnoses of this dynamic. In One-Dimensional Man (1964), he argued that in advanced industrial societies, material comfort and consumer abundance produce a “false consciousness” that pacifies opposition. People are offered just enough satisfaction, convenience, and choice to believe they are free - but these freedoms are “one-dimensional”, because they exist within a system that prevents diversity. Comfort and abundance create conformity: criticism is softened into opinion, authenticity is replaced by consumption, and identity is flattened into market categories. What looks like “diversity” becomes only variation within the same system. But affluent societies don’t just tame dissent; they hollow out the capacity for independent thought. When comfort, entertainment, and consumer choice are accessible, people internalize the system’s logic to such a degree that they repeat it as their own. Conformity becomes unconscious - and that is what makes it so powerful. Real identity, which depends on autonomy and self-awareness, is hollowed out. What remains is an identity regulated by external systems - markets, institutions, and cultural norms - aligned with the mainstream, unable to imagine otherwise.

What does that mean for avant-garde? Well, it is extremely difficult. But what makes avant-garde so difficult in affluent societies today is not only conformity, but the absence of resonance. On one side, people are numbed by the hollow repetition of fake identities, rehearsing mainstream scripts rather than living authentically. On the other, they are numbed by overstimulation: every image, gesture, and provocation has already been aestheticized, circulated, and consumed, leaving little that can cut through. Together, these forces create a silence of meaning - the conditions for resonance, for authentic recognition, are blocked.

Avant-Garde as Integrity (© Edie Lou)

Beyond Shock: Avant-Garde as Integrity

So, is there still room for the avant-garde in the Global North today? On the surface, affluence and saturation leave little space for rupture. The richer the system, the faster it converts defiance into product, turning rebellion into style. Yet it is exactly in such context that the avant-garde becomes necessary. In high-income democracies, political and cultural systems aim to maintain stability. This reduces existential insecurity for the majority of the citizens, but it also lowers the perceived need for systemic change. Yet this is precisely why avant-garde remains necessary. When conformity is rewarded and difference flattened, the task is not louder spectacle but deeper integrity: saying what others avoid, maintain positions that resist the pressure of assimilation.

What does that mean for the fashion industry? The avant-garde in the fashion industry today cannot rest only on silhouettes, seasonal shocks, or aesthetic gestures designed to scandalize. Those forms are quickly absorbed and recycled as style. What matters now is authenticity as practice: the refusal to mimic, to simulate, or to bend toward compliance. An avant-garde that counts must carry a political voice - no slogans! - but through work that openly defends human dignity. Even if it gets uncomfortable. If avant-garde means speaking truth where others bend, then today it must begin with the Global North, because it is here that silence, comfort, and complicity allow injustice to persist. Europe in particular carries a long history of colonial violence and racial hierarchy, and its current structures still reproduce those patterns - whether in its treatment on refugees, its foreign policy, or its selective recognition of suffering. The avant-garde must resist the European tendency to look away, to preserve its image of civility while sustaining systemic inequality.

So, the avant-garde in fashion today should look less like a style and more like a stance! Fashion that refuses to mimic what is profitable or legible, resisting the pressure to perform “sustainability”, “rebellion”, or “radicality” as marketing tropes. The political voice must be embedded into each stitch. Garments must carry a position - against war, racism, ecological destruction, discrimination. Radical humanism is required. Placing dignity at the center. It must be radically human - political, clear in its convictions, and steadfast in the face of injustice. Its work is to keep alive the possibility of truth where convenience demands looking away. Fashion must be slower, braver, and more truthful, refusing complicity with systems that profit from cheap labor, environmental destruction, and war or political violence.

Once these principles are clear, the rest follows organically. When dignity and care are established as primary values, exploitation is structurally excluded. Economic systems depend on trade-offs, but if the suffering of labor or ecological collapse is treated as a non-negotiable boundary, then the entire logic of pricing, sourcing, and distribution shifts automatically. This is not a matter of preference but of systemic coherence: values act as constraints, and constraints determine outcomes. In this sense, ethical commitments are not “add-ons” to fashion but formative parameters. Once embedded, they reshape the field, ensuring that design, production, and consumption cannot be separated from the conditions that make them possible. Fashion automatically evolves into a healthier ecosystem where outcomes are shaped by dignity, responsibility, and limits.

And nevertheless, clothes are never “just clothes”. A silhouette, a fabric, or a cut always carries cultural meaning - it signals class, gender, authority, rebellion, or belonging. A sharply tailored suit doesn’t only cover the body; it communicates hierarchy and conformity. A ripped T-shirt may signal rebellion or nonchalance. Avant-garde design does not require louder or more theatrical forms; its force lies in how these existing codes are reinterpreted. In this sense, the silhouette becomes a tool of challenging the system by repositioning meaning. The avant-garde does not live in garments alone, but in the integrity with which they are worn. A silhouette becomes radical when it carries the weight of authentic identity. A dress on a male body is not avant-garde anymore. But it becomes so when it is lived, chosen despite risk, despite leaving the comfort of safety. Like true punk.

The avant-garde in fashion is not extinct; it has simply changed its terrain. Its task today is not to shout louder, but to stand clearer - aligning design with principles of dignity, empathy, openness, and responsibility. When authenticity shapes both the garment and the stance behind it, fashion regains its power to unsettle what is complacent and to imagine what is still possible. That is the positive horizon: a future where avant-garde does not fade into spectacle, but persists as a living practice of integrity.

https://www.alainbrieux.com/opinions-litteraires-philosophiques-et-industrielles-ako62795.html

https://www.sciencespo.fr/artsetsocietes/fr/archives/3022

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/375468.Theory_of_the_Avant_Garde

https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/benjamin.pdf

https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-mechanical-reproduction/

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/349650.One_Dimensional_Man

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300233117/the-essential-duchamp/

https://writing.upenn.edu/library/Tzara_Dada-Manifesto_1918.pdf

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/270960.Flight_Out_of_Time

https://www.societyforasianart.org/sites/default/files/manifesto_futurista.pdf

https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/198/2629

https://openlibrary.org/books/OL3402958M/Dada

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300270952/fashion-at-the-edge/

https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/paris-fashion-9781474245494/

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/fashionology-9781350331884/

https://www.academia.edu/21148554/_Fashion_and_Surrealism_by_Richard_Martin

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/fashion-remains-9781350203167/

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/japanese-revolution-in-paris-fashion-9781859738153/

https://www.erikclabaugh.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/181899847-Subculture.pdf

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58849.Lipstick_Traces

https://www.sup.org/books/theory-and-philosophy/dialectic-enlightenment

https://www.metmuseum.org/met-publications/punk-chaos-to-couture

Martin Margiela Debut Show, 1989: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5nsQi9Yz3lo

Rei Kawakubo Destroy Collection, 1982: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBZfolU7p90

Commes des Garçons, 1997: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8yqlPfvTKY