fashion’s next horizon: a future rooted in real value and regeneration

The fashion industry has long thrived on illusion - the illusion of newness, manufactured desire, staged difference, sold belonging, and endless resources. But illusion does not last. As planetary systems approach irreversible tipping points, the age of performative sustainability is rapidly losing its legitimacy. What we face is not a branding challenge, but a material crisis: a reckoning with the real ecological and social limits that govern human life on Earth. Climate instability, biodiversity collapse, and the degradation of ecosystems are not future risks. They are active realities - and fashion, with its vast appetite for raw materials, human labor, and cultural capital, is deeply implicated.

For decades, sustainability has been flattened into marketing language: organic tags, recycled capsules, carbon offsets, soft-washed campaigns. Yet the logic of overproduction remains untouched. Circularity is promised, but not implemented. Human labor - the invisible core of the global fashion machine - remains precarious, exploited, and unaccounted for. Behind every seasonal drop lies a chain of extraction: from soil and water to body and time. And behind every trend cycle lies a deep cultural pattern: the performance of care without meaning.

Please, don’t get me wrong, this article is not another call for conscious consumerism. It is an argument for structural transformation - grounded in the science of planetary boundaries and anchored in the lived realities of those who manufacture, process, and transport the goods that fuel the fashion economy, often under exploitative and precarious conditions that remain structurally invisible to the end consumer. It is an attempt to rethink the future of fashion not through slogans, but through the interwoven realities of climate, labor, and meaning.

Planetary Boundaries (© of the original picture belongs to the rightful owner)

Living Beyond Limits: Fashion and the Breach of Planetary Boundaries

The planetary boundaries framework, developed by a team of earth system scientists led by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen, defines the environmental thresholds within which humanity can safely operate. It identifies nine essential biophysical thresholds that regulate the stability and resilience of Earth’s environment. These include climate change, biodiversity loss, biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus cycles), land-system change, freshwater use, ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion, and the introduction of novel entities (such as microplastics and chemicals). Transgressing these limits increases the risk of destabilising the entire planetary system. We are no longer operating near the edge of these limits; in multiple dimensions, we have already crossed them. Climate, land-system change, biochemical flows, and biosphere integrity have all moved into zones of high risk. The fashion industry, by its sheer scale and velocity, is directly implicated in nearly every one of these breaches.

Fashion’s ecological overshoot is not an abstract danger but a structural reality. The industry is fueled by overproduction, synthetic fibers derived from fossil fuels, intensive water use, chemical processing, deforestation, and carbon-heavy logistics. A staggering 100 billion garments are produced annually, the majority destined for short-term use before being discarded or down cycled. The scale is so excessive that no single effort - no material innovation, no recycling scheme, no carbon offset - can mitigate the systemic damage unless consumption itself is addressed. Ecological boundaries are not being stretched; they are being ignored. When fashion ignores limits, it not only loses cultural value - it accelerates ecological collapse. Overproduction leads to waste, pollution, and a flood of garments designed for landfill.

The breach of planetary boundaries is not merely an environmental concern - it is a moral one. It signals a civilisation unable to respect limits, to differentiate between abundance and excess, between desire and depletion. In this context, fashion becomes a mirror of our failure to respect boundaries and reveals the deeper dysfunctions of a system that overshoots planetary limits for profit. The question is no longer how to make fashion more sustainable within the existing system, but how to redefine the system itself. This requires more than regulation or technological “fixes”. It requires cultural maturity - a revaluation of slowness, durability, and sufficiency. A fashion culture that acknowledges planetary boundaries is not restrictive, it preserves the conditions that make creativity, culture, and life itself possible. It is generative.

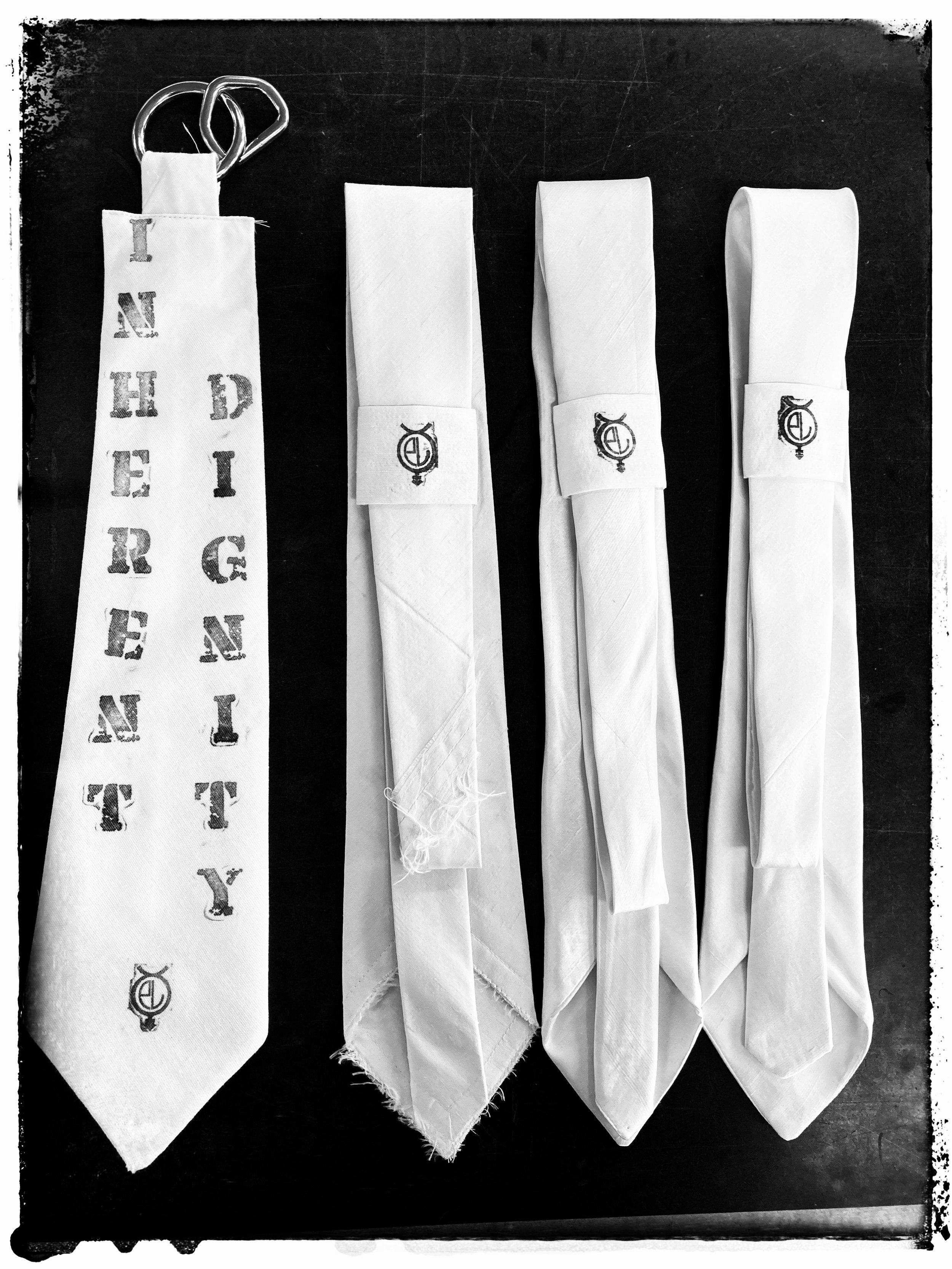

The myth of ethical fashion (© Edie Lou)

The Invisible Cost: Labor, Extraction, and the Myth of Ethical Fashion

If fashion’s planetary footprint reveals a dangerous rupture between industrial activity and ecological limits, then its social footprint exposes something just as urgent: the moral boundaries we are willing to ignore. The same system that overruns natural thresholds also operates through the systematic exploitation of human labor. Both crises are symptoms of the same structure - a system that extracts value while externalizing harm. In the logic of overshoot, nature is not the only thing made disposable. So are the people who sustain it.

And yet, much of the sustainability discourse avoids this reality. Brands speak of recycled materials and emissions targets, but they rarely acknowledge the workers - often underpaid and overexploited - who actually make the garments. The human cost remains ignored. Fashion brands often outsource production to countries with cheaper labor and weaker regulations. Fashion’s accelerated cycles depend on low-cost, high-volume labor: women in garment factories in Dhaka, teenage workers on spinning mills in Tamil Nadu, underpaid port workers moving cargo at scale. The problem isn’t just underpayment or overwork - it is the erasure of agency, safety, and visibility. These workers are rarely mentioned or seen in fashion’s narratives - they’re invisible to consumers.

Even when disasters like Rana Plaza briefly shatter this invisibility, the response has often been…let’s say: cosmetic. Since the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, some reforms have been implemented in Bangladesh: the Accord on Fire and Building Safety and Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety led to thousands of factory inspections and safety improvements. These initiatives have improved structural safety and fire compliance in many facilities. However, wages remain among the lowest in the world, unionization is weak, and retaliation against workers organizing is still common. In 2024, Bangladesh raised the minimus wage to about 12,500 taka ($114 USD/month) - but workers and unions say this remains far below a living wage. So while infrastructure and compliance have improved, the underlying model of cheap labor, high pressure, and limited agency has not fundamentally changed.

Factories, in turn, cut costs where they can - wages, safety, rights. But this pressure is not one-directional; it is systemic. Consumers, conditioned by decades of fast fashion and scout culture, have come to expect impossibly low prices as the norm. Clothes are purchased impulsively, worn briefly - if at all -, and discarded just as quickly - not because they “fail”, but because the cycle demands novelty. The faster something is bought, the sooner it is forgotten. As Yohji Yamamoto once observed, “People have started to forget what clothes are for.” Consumption has become not a relationship with clothing, but a response to boredom - fed by marketing, primed by social media, and reinforced by algorithmic suggestion. The problem is not just overproduction; it is disposability as mindset. In this culture, garments lose meaning the moment they were produced - and labor, by extension, disappears from view entirely.

Meaning, care, value (© Edie Lou)

Meaning, Care, Value

The violence of this system is both economic and symbolic. Fashion’s cycles depend on rapid turnover and surface novelty, not on deep relationships with materials, workers, or value. Even brands that manufacture in Europe are not exempt; “Made in Italy” means little when the labor is still precarious, underpaid, and the workers are undocumented. The challenge now is not only to expose these conditions - but to rewire the system itself: to build a culture in which human labor is no longer seen as a cost to minimize, but as the source of meaning, care, and value.

This cycle reflects also a deeper cultural indifference. Today, information is more accessible than ever. Consumers are quick to judge others for how they live, travel, or eat - yet rarely pause to question why a shirt can cost less than a sandwich. Fashion remains one of the few industries where the true cost of production is almost entirely ignored, and when sustainability is mentioned, it is nearly always reduced to materials not labor. The reason might be structural, and gendered. Still, in 2025. This is insane, don’t you think? Most garment workers are women. Their work is devalued, obscured, and rendered disposable - just like the garments they produce. This is not just economic injustice. It is systemic misogyny embedded in a global supply chain.

The result is a culture of disposability where clothes are consumed as strange content, not craft. And what is most unsettling is how normalized it has become - even among those who consider themselves ethically conscious. Many of the same consumers who identify as feminists or independent women participate in a system that exploits women’s labor on a high level. This contradiction is rarely acknowledged. In 2025, one might expect greater alignment between values and behavior, yet fashion remains the blind spot of feminist ethics. The question is here not simply how clothes are made, but who makes them, and why their stories remain unheard. Until that gap is closed - between values professed and systems sustained - fashion will remain one of the most polished fronts for structural inequality.

The answer on my side is not to boycott garments made in Bangladesh or other low-cost manufacturing regions. Doing so would collapse entire economies built around export production, and once again, it would be mostly women - the most vulnerable - who suffer first and most. The point is not abandonment, but accountability. The goal is not fewer jobs, but better ones. Consumers in wealthy nations must stop confusing novelty and lavishness with wealth. True value isn’t in constant change or excess - it is in care, longevity, and fairness. The illusion of abundance built on “cheap” garments hides a deep truth: overconsumption depends on the systematic underpayment of others. Someone, somewhere, is paying the real cost: with their time, health, or safety. And - of course - our planet.

The fashion system is burned out (© Edie Lou)

The Fashion System is Burned Out

The exhaustion of the fashion system is no longer just ecological - it is aesthetic, symbolic, and cultural. On one side, the sustainability imperative has exposed fashion’s systemic failures: planetary boundaries breached, human labor obscured, and storytelling reduced to greenwashed gestures. On the other side, the relentless churn of trends - the hyper-hype cycle, the algorithmic coolness, the commodification of identity - has reached a point of collapse. The style is tired. The audience is overfed but somehow undernourished.

Fashion is collapsing under its own contradictions. Researchers such as Ozdamar Ertekin have shown how the industry’s relentless pace amplifies exhaustion across the supply chain. The sustainability narrative - buzzwords about recycled textiles and carbon goals - no longer conceals the cracks in its foundation: breached ecological limits, hidden labor, and performative virtue. Meanwhile, the trend cycle - driven by algorithmic visibility and micro trends - has flattened into fatigue: the spectacle feels thin, the style exhausted, and the public increasingly numbed by novelty.

Ertekin’s work explores how fashion systems reproduce social and ecological harm, and how alternative consumption practices can challenge dominant paradigms. One of her key contributions is in analyzing slow fashion not merely as an aesthetic or ethical preference, but as a cultural resistance to fast fashion’s exploitative and extractive logic. In her co-authored paper, “Sustainable Fashion Consumption and the Fast Fashion Conundrum: Fashion with Limits,” (Journal of Macromarketing, 2015), she examines how limit-conscious consumers intentionally reject the speed and volume of mass-market fashion in favor of slower, more meaningful relationships with garment. This research helps explain the emerging shift away from excess and toward substance in fashion consumption today.

What Ozdamar Ertekin’s 2015 research anticipated was a cultural tipping point. But instead of triggering systemic change, that cultural signal was absorbed and down played by the market. What happened instead? The fast fashion model expanded uncontrollably. Ultra-fast platforms like Shein and Temu exploded by accelerating everything the slow fashion movement resisted: volume, speed, disposability, trend-churn, and labor invisibility - at scale and at algorithmic speed. So yes, it is shocking - but it also reveals the core contradiction of our time: knowledge is not enough. Awareness doens’t guarantee action. Cultural critique alone can’t compete with convenience and price unless the entire value system shifts - unless we change how we see value, and how we perform identity in a burned-out system.

(Un-)follow the system (© Edie Lou)

Follow the System

But why do people follow the mainstream? This is an urgent question - one that philosophers, sociologists, and psychologists have asked for centuries. Why are they drawn to repetition, mimicry, and pre-formed ideals? Why, even in a time of ecological collapse and cultural fatigue, do so many continue to consume what they don’t need and imitate what they don’t truly desire? Part of the answer lies in our nature. Human beings are social animals. From an evolutionary standpoint, we are wired for belonging. Following the group once meant survival. Today, it means social validation. Most people don’t want to be outcasts; they want to be seen, accepted, and aligned with what’s current. Mainstream trends - in fashion or otherwise - offer that safety. “People like us do things like this,” Seth Godin writes. Tribal logic still governs behavior. Being “in” is easier than being different.

Tribal logic doesn’t just govern taste or consumption; it governs identity at a fundamental level. The desire to belong - to be part of something larger, something recognizable - fuels not only fashion trends, but political ideologies, national myths, and cultural boundaries. Collective identity leverages this same evolutionary impulse: the deep human need to feel safe inside a group, often by defining and defending it against an “outside”. The cost of nonconformity is either way high. It threatens one’s social belonging - and belonging is often perceived as survival. What begins as a search of community becomes a mechanism of exclusion, and the emotional language of identity becomes a tool for control.

But the deeper reason is structural. The system trains us to be passive. Mainstream consumerism thrives on ease and repetition. It sells ready-made identities, reducing critical thought. Schools rarely teach media literacy or economic agency - and even in democratic societies, they often raise children to follow rules rather than question systems. The result is not critical citizens, but socially streamlined ones: equipped to participate, but not to reflect. This early socialization prepares individuals to accept the logic of the marketplace without resistance. Advertising then picks up where education leaves off. As Edward Bernays, the godfather of public relations, showed, it doesn’t merely promote products - it sells norms. Rooted in the mechanics of public relations, it manufactures desire and molds collective behavior, training us not just in what to buy, but how to think, feel, and belong. The result is a culture of conformity, carefully disguised as personal choice.

The market, too, depends on predictability. Capitalism, and do not get me wrong, I am part of it, especially in its algorithmic form, doesn’t seek individuals - it seeks optimized consumers. It favours behaviors that are legible, scalable, and easy to influence. From a young age, traditional, public schooling - in the most parts of the world - reinforces obedience and standardized thinking, conditioning citizens to follow rules rather than question them. This passivity becomes fertile ground for influence. Social media platforms then complete the loop: training users to mimic, perform, and conform. Algorithms don’t reward complexity; they reward repetition. In this ecosystem, trend adoption becomes a form of data compliance. Fast fashion, in particular, doesn’t just sell clothing - it manufactures desire at industrial scale, turning human attention into a commodity, identity into a transaction, and shopping into a form of social entertainment. What it offers is the illusion of belonging, novelty, and personal meaning - all delivered cheaply, and endlessly renewed.

Mainstream luxury fashion is not an exception. Though wrapped in the language of exclusivity, it follows the same emotional script as fast fashion: manufacturing desire, curating identities, and refreshing symbols of status at algorithmic speed. What was once anchored in scarcity and craft is now driven by visibility and trend responsiveness. The result is a luxury that behaves less like a cultural marker and more like a mass-media platform - distributing belonging, not meaning. Both, fast fashion and mainstream luxury now operate as two ends of the same extractive logic. One moves through price accessibility, the other through symbolic capital - but both manufacture desire at scale, flood the market with surplus, and depend on rapid turnover to stay culturally relevant. The result is not only aesthetic fatigue, but material waste. In chasing novelty and validation, they drive overproduction and normalize disposability - accelerating the fashion industry’s contribution to ecological collapse.

And finally, another reason why people follow, is not just ignorance - it is exhaustion. People aren’t always sheep because they’re shallow. Many are tired, overwhelmed, and economically insecure to take actions. Thinking differently requires time, education, and sometimes the luxury of distance. The system is built to keep people busy, indebted, and distracted. It sells relief - even if temporary, and it punishes slowness. So - why do people follow? Well, it is not just weakness, it is because the system is designed that way. Much of today’s consumer behavior is not just cultural - it is inherited. The postwar generations - shaped by scarcity and fear - built aggressively, equating consumption with progress, speed with success. That legacy - of acceleration, expansion, and appearance - is still with us. But it can be unleardned. The good news? Awareness is a first act of rebellion. People are waking up, even if slowly, but they need space, tools, and language to see through the circus - and build something different.

Every single garment carries the story of someone’s time, effort, and dignity (© Edie Lou)

What Comes Next

If there is one thing the fashion system makes clear today, it’s this: exhaustion is no longer metaphorical. It is planetary, human, and psychological. The earth is exhausted. Workers are exhausted. Consumers are exhausted - trapped in a cycle that promises self-expression but delivers disposability and emptiness. And while industry insiders have known for decades that change is necessary, the progress toward change in the fashion industry has been extremely slow, despite decades of awareness. Worse, even as the rhetoric of sustainability grows louder, ultra-fast fashion is rising, flooding the market with more volume, more speed, and more harm.

But what to do? Well,…part of the solution begins before adulthood, to be honest, in the narratives we absorb as children. Traditional schooling in most of the world still prepares individuals to follow, not to question. It rarely teaches economic agency or media literacy, and almost never explores how the system operates across industries - and how value is extracted. Education must be restructured to nurture critical thinking, empathy, and systemic literacy - not only in relation to fashion, but across all spheres of consumption and culture. It should equip to resist manipulation, and recognise the social, ecological, and human dimensions behind every product, service, and system we engage with. To value time, labor and lives of others is not a trend - it is the foundation of a just future. Parents, too, play a critical role as early role models. If care, maintenance, and conscious choice are normalized at home, the foundation for new values is set before the first purchase.

Changing the fashion system - truly and structurally - requires a shift on multiple, interconnected levels. First and foremost the consumer culture must be rewired. Real change starts with expectations. The transformation of the fashion system - or any system - doesn't begin only with regulations, innovation, or design. It begins with what people expect from the system. As long as consumers expect trend-driven garments at disposable prices, the system will respond with speed, volume, and exploitation. We must re-educate ourselves to value fewer, better-made items - and to recognize that cheap clothing often comes at a high human and environmental cost. Conscious consumption is not innate; it must be learned, model, and made aspirational. Even when affordability shapes what we buy, respect must shape how we use it. Garments should not be treated as disposable simply because they were inexpensive - someone’s hands made them, and that labor deserves care anyway. To recognize that is to begin buying less, wearing longer - because quality is not necessarily worse just because it is cheaper - and valuing more. We have to reframe value, move from price to worth - emotional, material, and ethical. And of course, slowness must be normalized - longevity, repair, and personal style must be more desirable than novelty.

And of course, business models needs to be redefined. Brands must shift away from exploitive models toward regenerative ones - not only in how they source and produce, but in how they price, communicate, and assign value. When a system is designed to extract, ethics become optional. But when dignity is built into the business model, every garment becomes a relationship: with a maker, a material, a planet. True cost strategy must account for fair wages and environmental impact. Design should sustain human lives through fair, stable, and dignified work. Fair wages, safe conditions, job security, and empowerment - especially for women in low-wage economies, access to income can mean autonomy, education, and a pathway out of poverty. Growth must be decoupled from volume; success must be measured by meaning, not magnitude. This includes embracing made-to-order models, eliminating overstock, and prioritising headstock or surplus sourcing - using what already exists before producing anew. A regenerative model does not ask how fast or how cheap, but how fair - and how lasting. It treats each decision as part of a wider ecology of care, where waste is not inevitable and excess is no longer aspirational.

And honestly, if a garment costs the same or less as a sandwich, someone is suffering. Fair wages matter. If we care, we pay. Period. To cheapskate on the labor of others is unethical. It is to offload the true cost of “beauty” onto someone else’s life. Creation only holds meaning when it honours those who make it. And we must also unlearn the idea that buying is a cure. Shopping is not therapy, and no object - however stylish - can fill an internal void. Buy less. Buy with care. Buying less makes you richer anyway - you save money, time, and energy you can invest in what truly matters. Not necessarily garments though - whatever matters to you. And never forget: every single garment carries the story of someone’s time, effort, and dignity.

https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol1/iss1/6/

https://gcris.ieu.edu.tr/handle/20.500.14365/2196

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272369672_Sustainable_Markets

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3828382-tribes

https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html

https://blogs.cornell.edu/info2040/2014/11/04/solomon-asch-experiment/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYIh4MkcfJA&t=4s

https://nature.berkeley.edu/ucce50/ag-labor/7article/article35.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8g1MJeHYlE0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KND_bBDE8RQ

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/493212.Propaganda

https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/

https://news.northeastern.edu/2024/03/21/magazine/fashion-supply-chain-forced-labor/

https://www.earthday.org/beneath-the-seams-the-human-toll-of-fast-fashion/

https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/fashion/overview