fashion’s transparency era: what digital product passports mean for everyone

The fashion industry is approaching a structural transformation that will alter how garments are designed, sold, and valued. By 2027, the European Union will roll out the first phase of Digital Product Passports (DPPs) for textiles - an ambitious regulatory framework designed to embed transparency and circularity into the very fabric of consumer goods. This shift will not only change how customers read clothing labels but also how brands manage supply chains, communicate values, and compete in the marketplace.

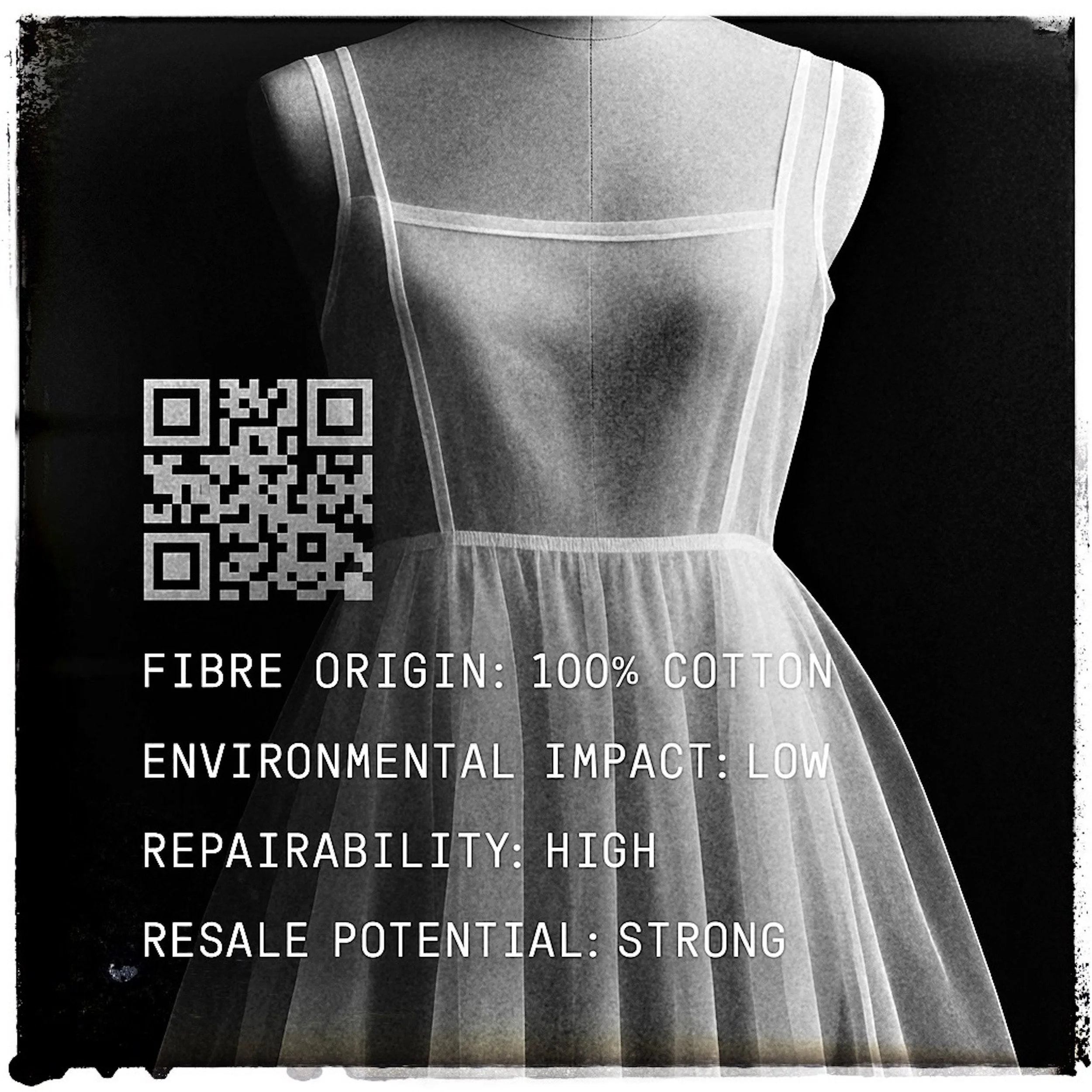

Unlike greenwashing slogans or symbolic sustainability gestures, the DPP introduces a mandatory system: a scannable, standardized, digital record attached to every product, containing data on materials, production, environmental impact, and end-of-life options. In practice, this means a standardized digital system - QR codes, NFC chips, or other identifiers - that every product must carry, linking it to a permanent, verifiable database. The information cannot be replaced by vague marketing claims; it is structured, regulated, and comparable across brands. In other word, the DPP shifts sustainability from storytelling into infrastructure: something built into the operating system of fashion itself, no longer optional, cosmetic, or easily manipulated.

The promise is both simple and radical: ssustainability will no longer rest on voluntary claims or vague slogans but on verifiable date accessible to all. Brands operated for decades within a global system that rewarded opacity - commodity markets that obscured origins, trade rules that privileged speed and scale, consumer demand for novelty at low cost, and weak regulation that left responsibility diffuse. The Digital Product Passport addresses this complexity by embedding accountability into the structure of the industry itself. For customers, it transforms shopping into an informed act - they will be making decisions with access to the product’s full biography. For brands, transparency used to be a choice - a marketing decision. Some brands voluntarily shared supply-chain information; many did not. With the DPP, transparency becomes a condition of participation in the European market. If brands want to sell in the EU, they must provide it. How brands handle this shift - whether they treat it as a bureaucratic burden rather than an opportunity or embrace it as a chance to build trust and an honest relationship with customers, remains to be seen.

While Europe leads with a regulated Digital Product Passport system, the U.S. remains fragmented. California and New York are advancing state-level laws on textile recovery and supply chain accountability, but there is no national equivalent. For global brands, this creates a dual challenge: prepare for the EU’s binding system while navigating a slower and uneven US system with fragmented state-level initiatives rather than a unified federal system. The direction, however, is the same - transparency is no longer a branding exercise but an emerging baseline for participation in the global market.

The Digital Product Passport (© Edie Lou)

Why the Shift is Necessary

The necessity of the Digital Product Passport becomes clear once we examine the structural realities of today’s fashion economy. The global industry produces an estimated 100 billion garments annually, more than double the volume of 2000. The European Environment Agency reports that textiles are now the fourth largest source of environmental pressure in the EU, after food, housing, and mobility. In 2020 alone, EU consumption of textiles generated 270 kilograms of CO2 emissions per person and required 9 cubic meters of water per capita. Yet most of these garments are discarded quickly: according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the average number of wears per item has fallen by 36% in the last 15 years, while less than 1% of collected textiles are recycled into new fibers. The scale of the problem is not incidental but systemic, obviously.

Crucially, the system is sustained not only by how brands produce but also by how consumers consume. Fast fashion has normalized both low price and high turnover: in Europe, the average citizen now buys 14 kilograms of textiles per year and discards around 11 kilograms. Online shopping and free returns have accelerated the cycle, with millions of unworn items destroyed or dumped annually. The World Bank estimates that fashion accounts for up to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, more than aviation and shipping combined. The model thrives on novelty and speed, reinforced by consumer expectations that garments should be plentiful, affordable, and disposable.

Opacity makes this dynamic even harder to confront. A garment tag typically lists only fiber content and country of final assembly - data that masks the long, fragmented chain of extraction, spinning, dyeing, finishing, and sewing that brought it into life. A garment tag saying: made in Italy or made in Romania refers only to the place of final assembly, not the whole journey of production. The reality is that most garments pass through multiple countries before they reach a shop floor. Cotton might be grown in India, spun in Turkey, woven in China, dyed in Bangladesh, and only then cut and sewn in Italy. Even seemingly minor details - threads, zippers, buttons, labels - are often sourced from different suppliers scattered across multiple continents. In this sense, the country-of-origin label is a simplification, it is simply misleading. Studies show that brands across the industry, regardless of size or market position, generally lack insights into their second- and third-tier suppliers, where the most exploitative labor conditions and environmentally damaging processes are concentrated.

This is not only a matter of oversight but also of structural complexity: with fibers, fabrics, and components often moving through multiple countries and subcontractors, full traceability remains difficult to achieve under current systems. But regardless of the reason, in the absence of standardized, product-level data consumers are left with marketing slogans rather than verifiable facts, while regulators struggle to enforce accountability across borders. Without verifiable data, greenwashing becomes the norm: in 2022, the European Commission found that 53% of environmental claims made by companies were vague, misleading, or unfounded.

It is within this context that the European Union has developed the Digital Product Passport. The DPP is a structural response to the limits of the existing system. On the supply side, voluntary sustainability initiatives and fragmented certification schemes have lacked consistency, comparability, and enforcement. They allowed brands to signal responsibility without being bound to full disclosure. On the demand side, consumer labels such as “eco-friendly” or “conscious” collections provided a white-washed sense of reassurance. Many shoppers embraced these signals as an easy way to silence doubt and justify continued consumption, preferring a clean conscience over critical reflection. The issue is straightforward: without verifiable, interoperable data, neither circularity nor accountability are possible. The passport reflects the recognition that fashion’s crisis is not about isolated bad actors but about a structural system that must now be re-coded at the regulatory level.

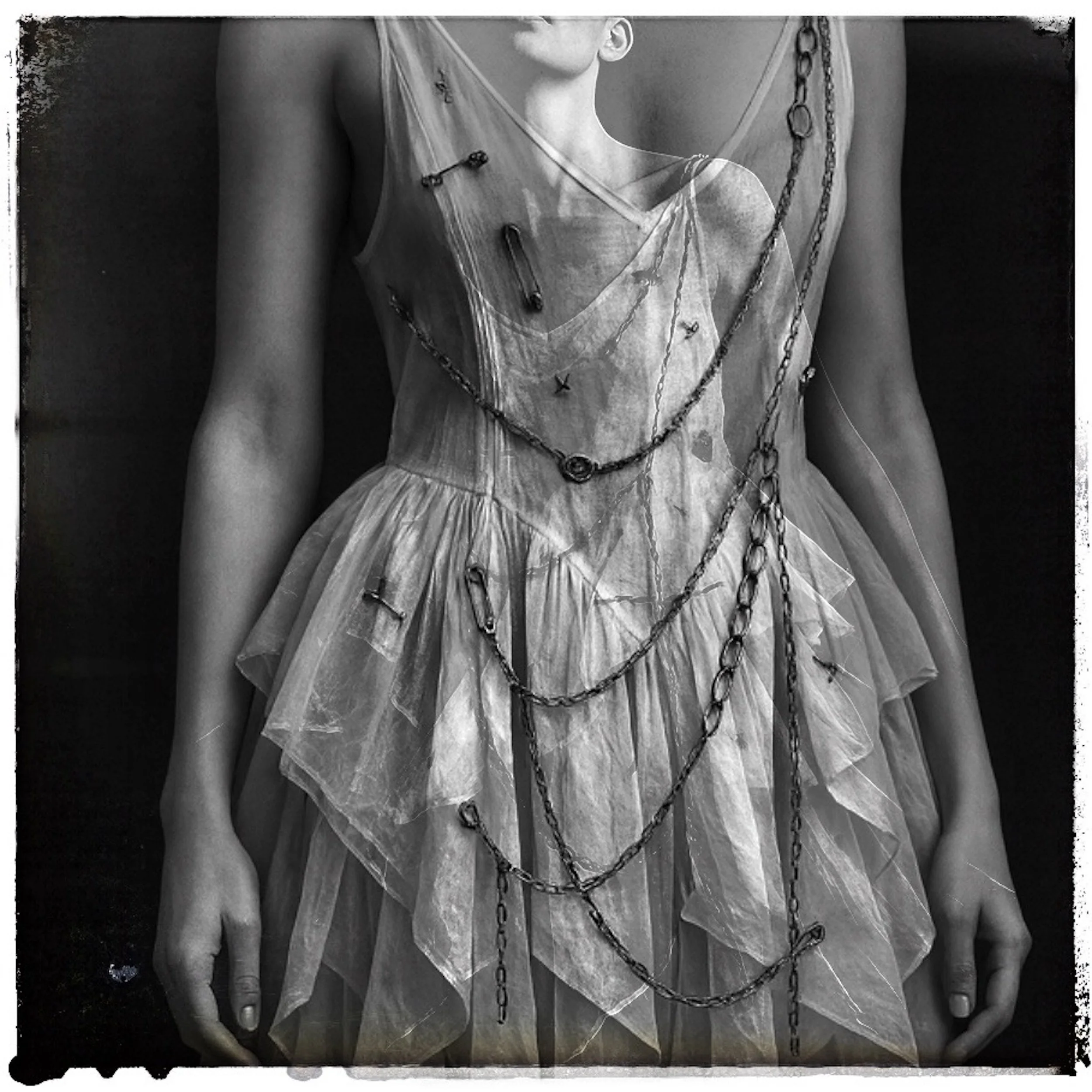

The DPP is a structural reprogramming of how fashion operates (© Edie Lou)

The Coming Shift

The European Union’s introduction of the Digital Product Passport is a structural reprogramming of how fashion operates. Beginning in 2027, textiles will need to carry a digital passport in order to circulate legally on the European market. This represents part of what the European Parliament describes as a “triple transition” - ecological, digital, and social - anchoring the industry within the wider Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan. In practice, the passport is designed to overcome the structural failures of the current system: opaque supply chains, unchecked overproduction, and the near total invisibility of social and environmental costs.

The reform is deliberately staged. In 2027, a minimal and simplified version of the passport will appear, limited in scope but mandatory for compliance. By 2030, this framework will expand into a more advanced system that incorporates additional lifecycle data and connects more stakeholders across the value chain, from recyclers to resellers. The final phase, envisioned for 2033, will bring the passport into full maturity as a circular economy tool, ensuring that every textile product carries the technical information needed for reuse, repair, and recycling at scale. This progression reveals both the ambition of the policy and its pragmatism: the EU is constructing not a symbolic gesture, but an evolving digital infrastructure capable of reshaping the entire industry.

The significance of this shift lies in its binding nature. For decades, sustainability in fashion has remained voluntary, fragmented, and easily co-opted by marketing. Brands could advertise “eco-friendly” collections or “responsible sourcing” without providing verifiable evidence. The Digital Product Passport breaks with this model. It makes transparency a condition of participation in the European market, embedding accountability into the product itself rather than leaving it at the discretion of corporate communications. This marks a decisive move from voluntary disclosure to enforceable obligation.

The Current Fashion Landscape

In cultural terms, the introduction of the passport is comparable to earlier regulatory milestones such as the nutrition label in food or the energy efficiency rating in appliances - as the European Parliament report and related EU Commission documents explicitly emphasize. The EU sees the DPP as a systemic, binding information tool that will embed sustainability and lifecycle data into fashion literacy. Consumers may not stop shopping mindlessly or debating what is “good” or “bad” fashion, but they will no longer be able to ignore clear, data-based information.

Before nutrition labels were introduced, most people had little access to information about what was inside their food. Calories, fat, sugar, and additives remained invisible, and choices were guided mainly by needs, taste, branding, and price. Once labels became mandatory, consumer behavior changed: literacy improved, dietary debates intensified, and companies were forced to reformulate products. At the same time, these labels also had a shadow side, intensifying food moralism and, for some, contributing to overthinking and body dysmorphia.

The same happened with household appliances. Before the EU’s energy efficiency label was introduced in the 1990’s, very few consumers factored electricity consumption into their purchases. A washing machine or fridge was judged by capacity, features, or cost, but not by long-term energy use. When the A-to-G scale appeared on every product in stores, it created a baseline of comparison that could not be ignored. Consumers began demanding more efficient models, and manufacturers redesigned accordingly. Over time, the least efficient products disappeared altogether - evidence that regulation can permanently reshape both demand and supply.

The EU Parliament hopes the Digital Product Passport will deliver a similar cultural reprogramming in fashion. Today, garments still circulate largely as aesthetic objects - defined by look, price, or brand heritage - while their environmental and social histories remain hidden. In this vacuum, both brands and consumers have grown comfortable: companies rely on recycled marketing slogans to signal responsibility, and shoppers accept them as reassurance while continuing established habits of consumption. By embedding verifiable data into every product, the DPP seeks to break this cycle, forcing both, producers and buyers, to confront the realities behind their choices. Every item will carry a unique identifier that reveals details such as material composition, supply chain steps, carbon and water footprints, labor due diligence, and repair or recycling options. The garment becomes a data-bearing object, inseparably linked to the wider systems of labor, ecology, and technology that made it possible.

What the Passport Contains

The Digital Product Passport is designed as a comprehensive dataset, one that moves far beyond current garment tags. Each product will carry a unique digital identifier, linking it directly to a passport that records sixteen categories of information covering the entire lifecycle of the garment. These categories begin with composition - detailing the exact percentages of fibers, including recycled or organic content - and extend to the origin of those fibers, the stages of spinning, dyeing, finishing, and final assembly, and the specific manufacturing sites where these processes take place. How garments and fibers were transported from origin to spinner, how they moved between dyeing and finishing facilities, and the modes of transport used at each stage.

Transport emissions and cross-continental outsourcing currently remain invisible in most reporting frameworks, even though they contribute substantially to a product’s environmental footprint, obviously. By forcing disclosure of distances and logistics choices, the passport introduces a new layer of accountability that directly challenges the industry’s reliance on complex, globalized supply chains designed primarily to minimize cost. Environmental and social data form the backbone of the system. Every product will disclose its greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption, energy use, and chemical inputs, alongside due diligence on labor rights, human rights risks, and working conditions. Where animal materials such as leather, wool, fur, silk, or feathers are used, the passport will record not only their presence but also the conditions of sourcing and welfare standards. The goal is not to overload consumers with data, it will happen automatically - but to replace broad claims of responsibility with structured, verifiable information.

Equally critical are the circularity dimensions. The passport will indicate durability, expected lifespan, and repairability, specifying whether spare parts such as zippers or linings are available. It will also clarify how fibers can be recycled, under what technical conditions, and how garments can be reused or resold beyond first ownership. Production volumes and quantities placed on the market will be tracked, giving regulators a clearer picture of overproduction. Finally, authentication features will secure originality and support the development of a trusted resale economy, ensuring garments maintain value across multiple lifecycles.

That means every brand that wants to sell in the EU must collect, structure, and upload the same categories of data into the passport system. Brands and manufacturers will be legally required to disclose data in a standardized format under EU regulation. Verification systems will be built into the regulation: some data will be audited by notified bodies or inspected by authorities, while others will rely on harmonized standards such as ISO and CEN to ensure consistency. The IT architecture will be interoperable, connecting QR codes, blockchain pilots, and GS1 standards so that different actors - regulators, recyclers, resellers, and consumers - can access the relevant layers of information. Not every category will be public: repairability, recyclability, and fiber origin will be consumer-facing, while more technical datasets will be available only to authorities or specialized actors.

Importantly, the Digital Product Passport is not a stand-alone tool but a part of a larger legislative ecosystem. It is anchored in the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), aligned with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and reinforced by the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Together, these laws make it impossible for garments to circulate on the European market without carrying verifiable data about their origin, impact, and potential future. The Digital Product Passport becomes a condition of market access in the EU. If a garment does not carry a DPP, it will simply not be allowed to be sold in Europe.

The ESPR sets the technical rules for what information must be collected and how it is structured. The CSRD obliges companies to report on sustainability impacts in a standardized way, aligning corporate disclosures with the product-level data in the DPP. And the CSDDD extends responsibility for labor and human rights risks across supply chains. Together, these laws close the loopholes of voluntary disclosure. Today, a brand can sell in the EU while providing only minimal or vague information (e.g. “Made in Italy” or “responsibly sourced cotton”). After 2027, every textile product must carry a DPP with verifiable, standardized data. Without it, the product will not meet legal requirements and circulate in the market.

What the Passport Means for Brands (© Edie Lou)

What the Passport Means for Brands

For the industry, the Digital Product Passport is not just another compliance requirement but a restructuring of how market access is defined. The DPP applies across the board - luxury houses in Paris, suppliers in Dhaka, and independent designers in Los Angeles, Zurich and Copenhagen. For decades, luxury and mass-market fashion alike have extracted profits by keeping large parts of the production chain invisible. The branding and pricing power sat in Paris, Milan, or New York, while the real cost of labor, resource extraction, and environmental damage was externalized to suppliers in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Peru, or Mongolia.

The “Made in Italy” or “Made in France” label became shorthand for prestige, even when most of the value chain had already taken place elsewhere, under inhuman conditions: unsafe factories, poverty wages, excessive overtime, exposure to toxic chemicals, and systematic denial of rights. And it is not just labor that has been made invisible, but also the extraction from nature and the use of animals within the fashion system that has taken place with devastating ecological consequences: deforestation for cattle ranching, desertification from overgrazed cashmere pastures, toxic runoff from dye houses polluting rivers. Agriculture, too, has been part of this hidden cost: cotton cultivation in monoculture systems depletes soils and drives ecological degradation.

So, the question is, will luxury and mass-markets alike be able to reinvent their narrative - moving from symbolic opacity to data-backed authenticity - while preserving their profit model? Or will the DPP mark the beginning of a necessary profit correction and product size regulation, where margins shrink because hidden costs are finally brought into the light? If the real costs of labor, agriculture, animal welfare, and ecological impact are finally acknowledged and factored into production, then the profit margins of today’s giants cannot stay the same. If brands had always paid the real prices - for fair labor, sustainable agriculture, animal welfare, and ecological stewardship - then the industry wouldn’t face today’s crisis of credibility and regulation. The current margins of giants exist precisely because these costs were externalized, hidden, or absorbed by the most vulnerable.

Luxury brands will no longer be able to justify astronomical mark-ups purely through symbolic narratives while paying minimal upstream. If they start paying true costs - fair wages in supply chains, ecological safeguards in fiber production, animal welfare standards - their margins will probably shrink. Drastically. They can still remain profitable, but not at the same level of accumulation they have enjoyed by externalizing the costs. But the challenge is existential. They got rich on exclusivity that was symbolic, built on phrases like “craftsmanship” or “heritage”, while raw fibers, labor, and environmental costs were hidden offshore. Behind these narratives, many houses played the same game of scale, overproduction, and disposability, relied on the same mass-market strategies like fast-fashion. The recent Loro Piana scandal revealed how even the most prestigious names were entangled in supply chains that contradicted their image, exposing the fragility of symbolic authenticity when confronted with traceable data. The DPP will make this kind of double standard increasingly untenable, forcing luxury to reconcile its mythology with material reality. If those houses do not radically rethink their narrative, the aura of luxury risks being punctured. Only those who can reposition luxury as traceable, durable, and verified will survive with legitimacy.

For fast fashion, the DPP is even more threatening. Their business model is built on speed, volume, and invisibility. If for luxury the Digital Product Passport threatens to unravel the myths of heritage and exclusivity, for fast fashion the struggle is of another order. They cannot survive easily once transparency becomes mandatory. The possibilities here are limited. Either fast fashion players radically restructure, slowing down their volumes and proving every claim with verified data, or they retreat to less regulated markets where opacity can still operate. For brands like Shein, the challenge is existential. Its entire business model depends on opacity: hyper-speed, hyper-volume, and hyper-disposability. Tens of thousands of new styles are uploaded daily, with prices so low that the labor, water, and chemical costs must remain invisible. The DPP makes that invisibility impossible. Every garment sold in Europe would need a scannable passport showing its fiber origin, emissions, and labor footprint, alongside data on the sheer volumes being placed on the market. This collapses the illusion of “cheap abundance”. Shein can either radically restructure, which erases its competitive edge, or exit regulated markets and focus on regions without transparency laws. A third option - a minimal “compliance line” for Europe alongside opaque operations elsewhere - risking exposure of the double standard. Well… In short, Shein cannot coexist with full-scale transparency - its very DNA is incompatible with the DPP.

H&M is different. Unlike Shein, it is already established in Europe, has invested in sustainability pilots (rental programs, textile recycling, conscious collections), and has a corporate history of working with regulators. But its scale remains a problem: millions of garments churned out every year, with supply chains stretching into some of the most fragile labor and ecological regions. The DPP will force H&M to confront not only how much it produces but also to verify every claim it has made in the past about sustainability. For H&M, survival is possible - but only through radical transparency, slower volumes, and using the DPP as proof of transition rather than as a compliance burden. While it cannot fully transform into a transparent luxury player, parts of H&M could pivot “smaller and slower”: premium sub-brands like COS or Arket might evolve into curated, high-quality, transparent lines designed to comply with European regulation. This would create a dual strategy- risking again exposure of the double standard - structure, premium and compliant in regulated markets, high-volume and opaque elsewhere.

Transparency in motion (© Edie Lou)

Beyond the European Union: Switzerland and the U.S.

The impact of the Digital Product Passport is not confined to brand categories - luxury, fast fashion, etc. - but also shaped by geography. Where a brand is based, and which markets it relies on, will determine how quickly and deeply it must adapt. Europe will set the pace, while other regions will be drawn into its orbit in uneven ways. The DPP is a European initiative, obviously, but its impact will not stop at the EU’s borders. Switzerland offers the clearest example. Though not an EU member, it is economically entwined with the single market through a web of bilateral agreements. For Swiss fashion companies—from heritage houses like Bally and Akris to young independent labels—compliance will be unavoidable if they want access to EU consumers. Domestically, however, Switzerland has no equivalent regulation in place. Existing initiatives, such as the Swiss Sustainable Textiles program, remain voluntary. This asymmetry creates a shadow zone: at home, brands may continue under lighter expectations, while abroad they face the binding transparency of the EU passport. For smaller Swiss labels, the situation may even be advantageous. By aligning early with EU rules, they can position themselves as leaders in authenticity and credibility, turning compliance into a competitive edge. For larger players, by contrast, the mismatch between domestic leniency and EU stringency risks exposing the inconsistencies in their operations.

The U.S. presents a different picture. Unlike Switzerland, it is not economically tethered to the EU, and regulatory momentum is slower and more fragmented. California has introduced the Garment Worker Protection Act and New York debated the Fashion Act, but these remain regional efforts rather than national law. The U.S. lacks a federal equivalent of the Digital Product Passport, and the political climate makes sweeping sustainability regulation unlikely in the short term. Yet, American brands will not be insulated. To sell in Europe, they too will have to comply with the DPP, reconfiguring their supply chains even if domestic consumers are not demanding it. For giants like Ralph Lauren, Nike, or PVH, this means managing dual regulatory landscapes: minimal requirements at home, maximal requirements abroad.

This duality reveals how the EU is effectively setting the global standard. Just as its rules on data privacy (GDPR) reshaped digital industries worldwide, the DPP has the potential to establish a baseline for fashion transparency that extends far beyond its borders. Switzerland and the U.S. illustrate two variations of the same reality: in a globalized economy, no brand can escape European regulation. Whether through economic interdependence or market power, the EU’s framework will define the conditions of participation. For some, this will mean compliance by necessity; for others, it will be a chance to lead.

Yet the DPP’s reach extends beyond consumer markets. It will filter through supply chains, reaching the factories in Bangladesh, India, or Vietnam that produce the majority of the world’s garments. For them, the new system is double-edged. On the one hand, it holds the potential to reveal the inhuman conditions, suppressed wages, and monoculture agriculture (cotton especially) that underpin the cheapness of global fashion, forcing greater accountability from the brands that source there. On the other, compliance will demand new systems of data tracking and verification that many suppliers cannot finance alone. Unless brands actively invest in their partners’ capacity to meet these standards, the passport risks creating a split world: compliant, well-funded suppliers able to access European markets, and vulnerable factories excluded or pushed deeper into precarity.

Fashion’s Transparent Future

While the transition will be demanding across the industry, small and emerging brands are uniquely positioned to approach it differently - embedding transparency from the start rather than trying to adjust long-established systems. Unlike conglomerates, which must reorganize sprawling supply chains and justify margins built on opacity, independent labels are structurally more agile. Their production runs are smaller, their supplier networks shorter, and their customer relationships more direct. For those brands a Digital Product Passport can be a real opportunity: it allows them to embed transparency from the start. DPP is less a bureaucratic hurdle than a chance to embed transparency from the beginning - turning regulation into a sign of integrity rather than a threat to survival.

Where large companies have to rework complex systems to meet new standards, strartups can design with these standards already in place. Traceability becomes a natural extension of their design and sourcing, not an extra layer forced from the outside. This agility gives small brands the chance to lead by example, showing that fashion can operate at a human scale without concealing the true costs of production. For decades, many fashion brands - especially luxury houses - have built their prestige on secrecy. Customers were encouraged to believe that the name and the heritage of the brand was enough proof of quality and ethicality without knowing where the garments came from, who sewed the clothes, or what impact production had on the environment. For years, secrecy itself has been treated as a sign of sophistication in fashion, with exclusivity narratives taking the place of real transparency. And in an industry long defined by secrecy and image-making, openness may well become the strongest competitive advantage of small startup brands.

The passport also provides a new way for small labels to tell their story. A scannable record of fiber origin, environmental impact, repairability, and resale potential serves as proof of values - authenticity expressed in verifiable data. For young labels competing in a crowded market, this convergence of regulation and communication is powerful. It allows them to present transparency as part of their identity - setting them apart from the defensive strategies of larger players. And let’s face this: many brands already produce to order - avoiding overproduction naturally - use deadstock fabrics as a resource, sustainability is part of their DNA. For those labels, the Digital Product Passport is less a disruptive shift than a natural extension of how they already operate - an organic flow rather than a forced adjustment. But this potential depends on accessibility: if the passport is built around costly, complex data and PLM systems that only large corporations can afford, small brands risk being excluded from the very transparency shift they are best placed to lead, honestly. In a democratic system, however, the DPP cannot be designed this way. If transparence is to become the new foundation of fashion, the tools for delivering it must be inclusive, scalable, and fair.

And nevertheless, regulation can address structural failures, but it cannot create integrity or restore humanity. At best, it sets minimum standards; it cannot replace moral courage or the willingness to act with responsibility by choice. More importantly, it is a cultural loss that such measures are even necessary. Ideally, fashion or all other industries, would not need regulation to enforce integrity; values of care, responsibility, and transparency - why do people struggle with this? - would be lived by choice. Kohlberg’s framework of moral development reminds us that the higher stage of ethics is not compliance under pressure but acting from inner conviction. The very fact that regulation is required shows how far both industry and consumers have drifted from moral courage. For small brands, the task is to prove that another way is possible - where transparency is not an enforcement, but a foundation for trust, responsibility, creativity, human dignity, and authenticity.

https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7854-2022-INIT/en/pdf

https://cleanclothes.org/file-repository/underpaid-in-the-pandemic.pdf

https://gs1.eu/activities/digital-product-passport/

https://acris.aalto.fi/ws/portalfiles/portal/32741443/Sustainable_Fashion_in_a_Circular_Economy.pdf

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/putting-brakes-fast-fashion

https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/fashion/overview

https://unece.org/forests/events/sdg-9-fashion-industry-innovation-and-infrastructure

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/new_garment_manufacturers_and_contractors.htm

https://legiscan.com/CA/text/SB62/id/3260245

https://www.sts2030.ch/?lang=en

https://swisstextiles.ch/en/issues/swiss-textiles-supports-the-climate-protection-act