Inside collection development: ready-to-wear, runway, haute couture, and independent brands

Collection development remains one of the least visible yet most structurally determinative processes in the fashion industry. While runway shows capture cultural attention and retail strategies generate revenue, the work that occurs between these two poles defines the creative, economic, and operational trajectory of every brand. This development cycle determines whether an idea becomes a viable garment, whether a concept can survive material constraints, and whether a collection aligns with the broader identity and strategic direction of a house. In this sense, collection development functions as the industry’s internal architecture: technical, iterative, and largely unseen - whether the outcome is a commercial ready-to-wear line, a highly conceptual runway collection, or a haute couture presentation realised through hand-finishing, artisanal techniques, and the regulated standards of the haute couture ateliers.

For luxury houses, independent designers, and contemporary ready-to-wear labels, the process is shaped by a combination of conceptual research, material sourcing, supply-chain logic, and organisational decision-making. Designers operate within a coordinated workflow involving pattern makers, textile specialists, merchandisers, and atelier staff, translating conceptual research into garments that meet both aesthetic and production requirements. Early design work often branches into distinct pathways: ready-to-wear development priorities precise decisions on market positioning, material specifications, technical feasibility, and cost management, ensuring that garments can be produced consistently, priced competitively, and delivered at scale, whereas runway pieces serve a distinct strategic role. They allow for heightened experimentation in silhouette, fabrication, and construction, and operate less as commercial products than as instruments of brand identity, PR visibility, and creative storytelling - establishing the aesthetic and conceptual direction that supports the rest of the collection.

Haute couture adds an additional layer of complexity: governed by the Chamber Syndicale de la Haute Couture and bound by strict criteria involving atelier capacity, craftsmanship, and client service, couture development demands months of handwork, bespoke fittings, and artisanal labor. However, drawing on established work by Craik, and McRobbie, it becomes clear that collections - whether couture or ready-to-wear - arise from structured, collaborative processes rather than singular bursts of creativity. This work unfolds within the structure of the global fashion calendar, which sets the tempo for development, with New York, London, Milan, and Paris defining the annual cycle. These fixed dates determine when research begins, when prototypes must be completed, and when production must start, making collection development both a creative process and a tightly timed industrial workflow.

Commercial Ready-to-Wear, Runway Collections, and Haute Couture

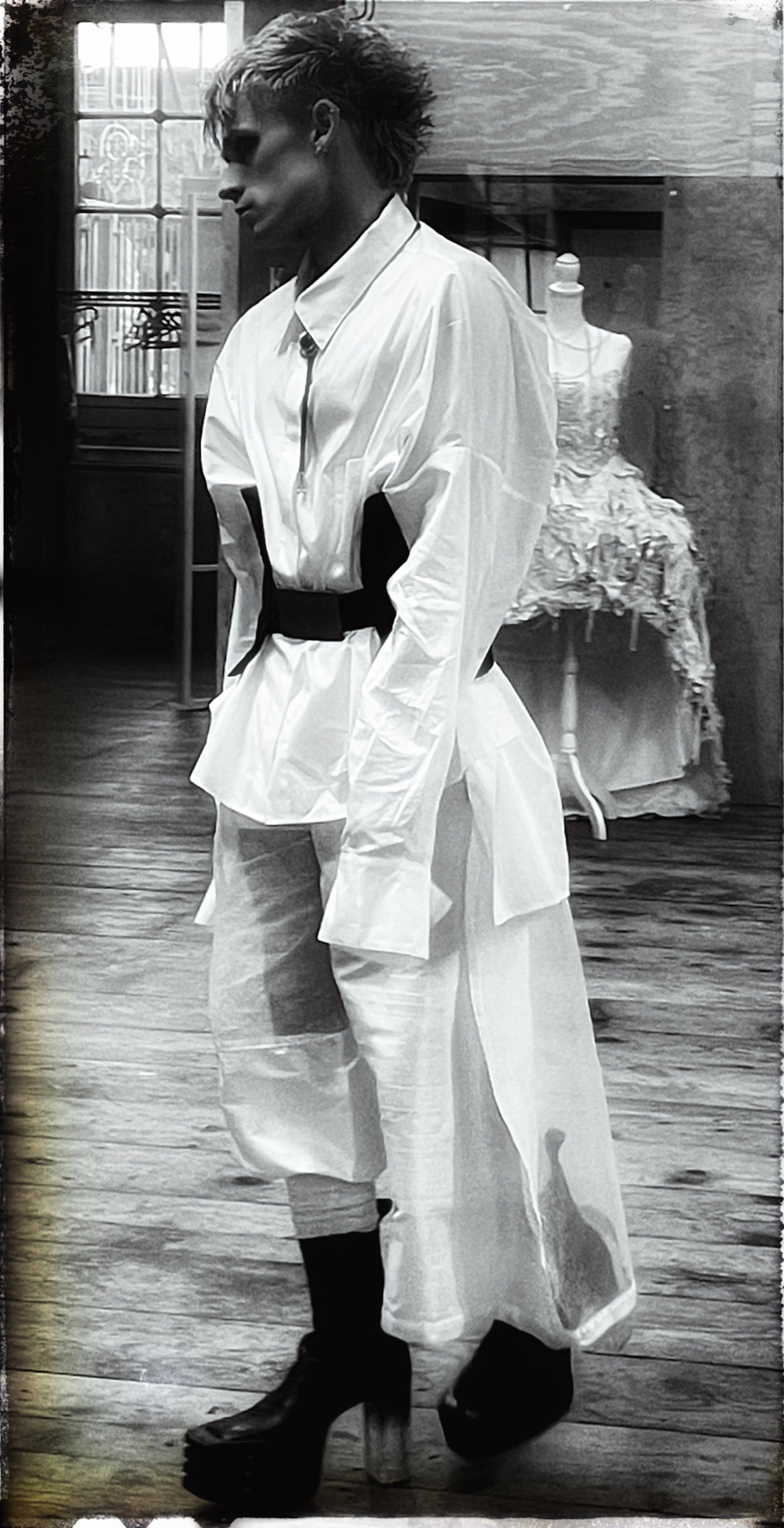

Commercial ready-to-wear also operates within rigid delivery calendars (© Edie Lou)

Ready-to-Wear

Collection development begins with a distinction between three principal outputs that structure design work Innside contemporary fashion houses: commercial ready-to-wear, runway collections, and haute couture. Around these core categories sit additional formats such as Pre-Fall, Resort, capsule projects, and bridal, but the primary creative methodologies and organisational processes are built around the first three. Although they may emerge from the same design studio, they operate under different constraints, communicate different forms of value, and require different levels of technical and organisational commitment.

Commercial ready-to-wear forms the financial and operational core of most fashion houses, and its development is guided by a tightly defined set of constraints that balance creativity with industrial reality. Every decision is shaped by cost structure, scalability, and market expectations. Designers work within established block patterns, construction methods, and sourcing frameworks, because deviations introduce risk: new materials may not meet performance standards, unfamiliar constructions may slow production, and excessive complexity can destabilize margins. Ready-to-wear therefore requires a high degree of technical discipline. Silhouettes must be reproducible across full size runs, fabrics must be consistently available in commercial quantities, and trims must meet both price and lead-time parameters.

The production planning process reinforces this discipline. Merchandisers determine the breadth and depth of the line - how many silhouettes, how many colorways, and how many un its per style - based on past performance and projected demand. Technical designers translate creative sketches into specifications that factories can execute with precision, ensuring every measurement, construction detail, and finishing requirement is clearly defined. Sourcing teams secure materials that can be reordered at scale and adhere to required testing standards. Sampling rounds test feasibility: prototypes are assessed for sewing efficiency, material behavior, and cost per unit. Adjustment reflect manufacturing logic as much as design intent. During ready-to-wear development, changes to a designer not made only because the designer wants them - they are often made because production realities require them.

Commercial ready-to-wear also operates within rigid delivery calendars. Wholesale deadlines, retail drops, and global shipping windows determine when each garment must be finalised and approved. Missing these dates compresses production, increases error rates, and often leads directly to markdowns. As a result, the creative process is synchronised with logistics and production capacity. The success of ready-to-wear is therefore measured empirically: sell-through percentages, return rates, margin integrity, and reorder velocity. In this segment of the industry, value is validated not by cultural symbolism in the first case - but by the garment’s ability to move efficiently through the supply chain and meet the expectations of a specific customer with precision and consistency.

The main purpose of ready-to-wear depends entirely on the scale and structure of the brand. For global luxury houses, ready-to-wear is not designed to be the primary profit driver; its main function is to reinforce the brand’s creative identity - an identity translation into marketable product - set the aesthetic direction for the season, and supports indirectly the cultural prestige that elevates sales in high-margin categories like leather goods, fragrance, beauty, accessories, and licensing - licensed products are categories a fashion house does not produce itself but allows another specialised company to produce under its name, in exchange for a fee or a share of profits. They are extremely common in luxury because they generate high revenue with low operational burden. However, in this context, ready-to-wear is a strategic communication tool. For independent designers and small labels, the purpose is very different: ready-to-wear must generate the majority of revenue because they lack the diversified product architecture of conglomerate-owned brands. Obviously, this is the case, because of their size. Diversification is only possible when a company has enough capital, infrastructure etc. Here, the focus is on feasibility, sell-through, and financial survival. The same category therefore carries two distinct purposes - branding for luxury houses, and economic viability for independent ones.

Runway collections represent the most conceptually ambitious output of a fashion house (© Edie Lou, shoes Rick Owens)

Runway Collections

Runway collections represent the most conceptually ambitious output of a fashion house. Their primary function is to articulate the brand’s seasonal direction - silhouette logic, material language, construction ideas, cultural references, and the overarching narrative that will inform all other product categories. Unlike commercial ready-to-wear, runway pieces are not developed to meet defined retail price points, fit standardization, or the manufacturing efficiencies required for larger-scale production. They exist to define identity rather than to drive volume. Runway collections are created to define the artistic and cultural identity of a house; their purpose is expressive rather than commercial. For this reason, runway collections operate on a fundamentally different logic: their value lies in visibility, press impact, and cultural authority. They generate the cultural authority of the house. They set the narrative, produce the imagery that circulates globally, and determine the ideological direction of the brand - its visual codes, aesthetic position, and conceptual framework - while defining the narrative that will inform both the season and the broader identity of the label.

Runway development begins months before the show and follows a workflow that is concept-driven rather than margin-drive. Designers establish the season’s conceptual framework through research, mood boards, color boards, fabric boards, and early silhouettes studies, often in close collaboration with pattern makers and atelier staff. Prototypes are built through iterative experimentation for conceptual and visual impact, not for functional durability or production efficiency. Their purpose is aesthetic, directional, and communicative, designed to generate cultural impact, press visibility, and brand positioning. Garments may be technically complex, fragile, or finished in ways that would be impractical for production. their value lies in shaping the brand’s narrative, generating public relations momentum through press coverage, social media visibility, and cultural signaling.

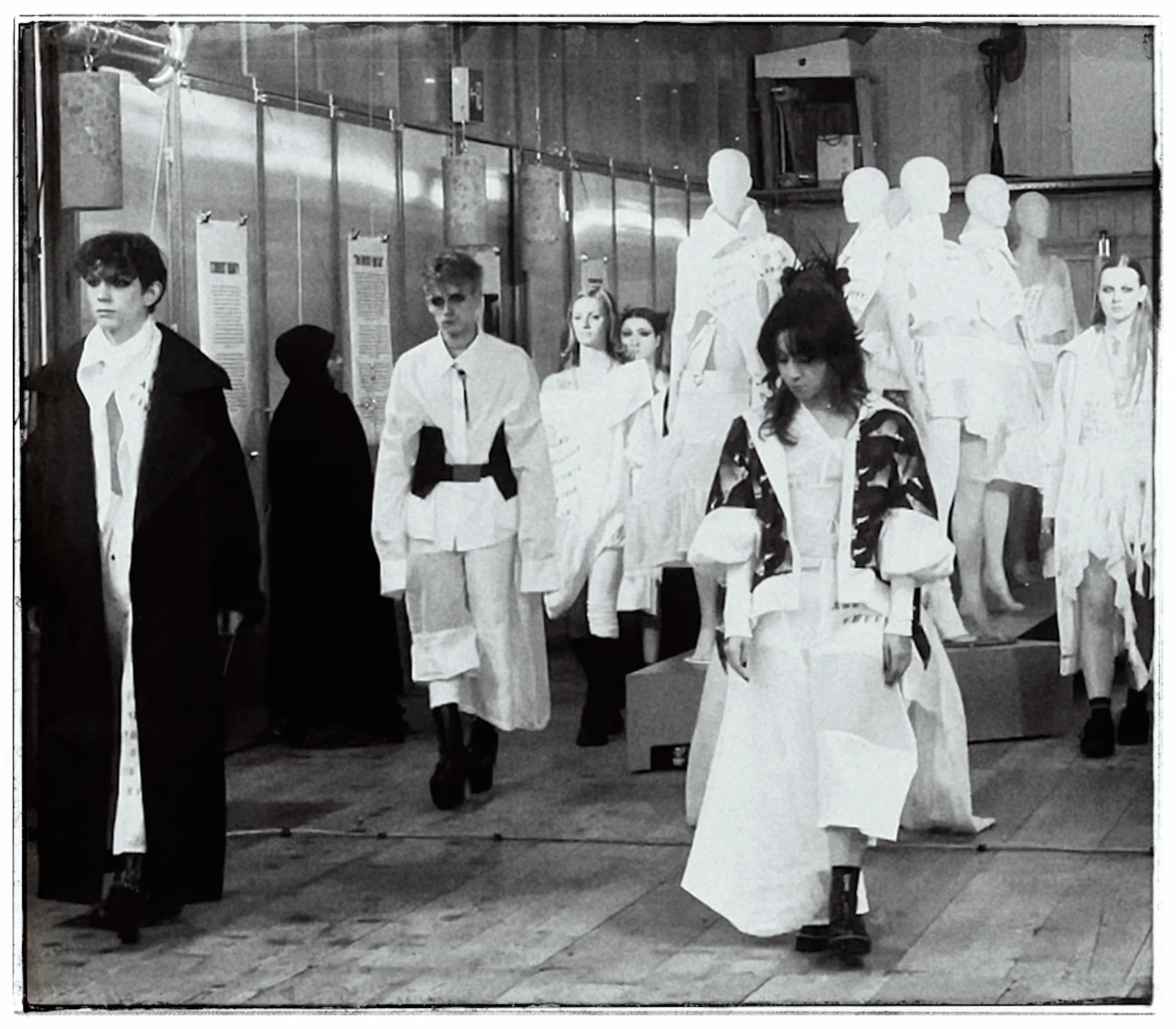

So, garments are built thorugh iterative experimentation, involve exaggerated forms, hand-intensive techniques, or construction methods that cannot be reproduced at scale. At the collection evolves, teams conduct multiple rounds of fittings, material trials, and fabrication tests to determine which looks carry the brand’s narrative most effectively. In the later stages, external partners become integral: casting directors, stylists, show producers, sound designers, and production agencies coordinate staging, music, space design, and overall show flow. Runway development is a process fundamentally different from the structured, efficiency-focused product development required for commercial ready-to-wear. Runway development is artistically oriented: its primary objective is creative expression, narrative clarity, and cultural impact.

But…to make everything a little less clear and boost confusion: although runway collections privilege conceptual, visually impactful pieces, many brands integrate selected ready-to-wear garments into the show. These commercial looks are adapted for the runway through styling, acting, and presentation, but remain fundamentally designed for production and sale. This hybrid approach serves a dual purpose: the conceptual looks generate cultural visibility and PR momentum, while the embedded ready-to-wear pieces connect the runway narrative to the commercial line that will enter stores. In contemporary practice, runway presentations therefore function as both artistic statement and strategic merchandising tool.

Independent shows sit outside the formal fashion-week system yet play an increasingly important role in contemporary practice. Designers without access to Paris, Milan, London, or New York often build their own presentation formats - from small runway productions to installations, lookbook events, or hybrid performances. these formats are not simply substitutes for established fashion events; they serve a different strategic function. They allow emerging brands to articulate their identity on their own terms, to engage directly with their immediate community, build relationships with their audience, and of course, test ideas without the pressure of wholesale cycles or buyer-driven expectations. In this context, an independent fashion show becomes both a communication tool and a cultural statement: one that prioritises community, specificity, and cultural coherence over scale, and that relies on networks, direct engagement, and authentic human contact. This creates a clear structural advantage: independent shows enable emerging brands to build genuine proximity to their audience, deepen their network, and communicate identity without the distortions introduced by traditional industry gatekeeping. But, whether a major luxury house or an independent label - the garments shown on the runway function as samples; after the presentation, they enter the archive and not the sales floor, while the versions intended for clients or production are developed separately.

Couture is governed by the Chamber Syndicale de la Haute Couture (© Edie Lou)

Haute Couture

Haute couture represents the most technically demanding and institutionally regulated form of collection development in the contemporary fashion system. Unlike ready-to-wear or runway collections, couture is governed by the Chamber Syndicale de la Haute Couture (now under the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode), which defines strict criteria regarding atelier size, craftsmanship capabilities, the number of full-time artisans employed, and the requirement to produce bespoke garments for private clients. These standards ensure that couture remains an artisanal discipline rooted in hand-work, precision, and the maintenance of rare technical skills.

The development of a couture collection follows a fundamentally different logic than commercial product creation. The process begins with conceptual direction, but once the theme is set, the focus shifts to technique rather than scalability. Garments are draped directly on the body or dress form, with silhouettes resolved through initial toile fitting, intermediate fitting, embroidery/decoration fitting, finishing fitting, and final client fitting. So couture begins with draping, not flat pattern drafting. The toile is usually built in cotton muslin and shaped directly on a dress form or on a live model. Silhouettes are established through physical manipulation, not technical drafting in the first case. Couture is defined by the contribution of highly specialized métiers, including petites mains - seamstresses, tailors - flou ateliers - soft dressmaking - tailleur ateliers - structured tailoring - embroidery houses, feather work, pleating specialists, milliners, shoemakers, glove makers, textile manipulations workshops etc. Each component is produced by artisans recognised for a single skill set, and the couture houses rely on the métiers d’art ecosystem that supports them.

Timelines are compressed and labor intensity is extreme; a single garment can require hundreds to thousands of hours of manual work. The absence of price constraints or production feasibility considerations allows designers to push construction, form, and materiality far beyond the limits of ready-to-wear. Couture pricing reflects this intensity. Daywear pieces typically begin around $20,000 - $40,000; cocktail dresses range from $ 40,000 - $80,000; and evening gowns, depending on embroidery and technical complexity, span $80,000 - $150,000 or more. Highly embellished gowns, often involving specialist ateliers such as Lesage, Monte, Lemarié or Lognon, frequently exceed $150,000 - $300,000. Bridal couture - the most labor-intensive category - ranges from $120,000 to $400,000, with exceptional commissions surpassing $1 million. These prices reflect cumulative hours of manual work, the expertise of multiple ateliers, and the bespoke nature of fitting and fabrication. For many clients, seasonal spending easily reaches $100,000 - $500,000 or more.

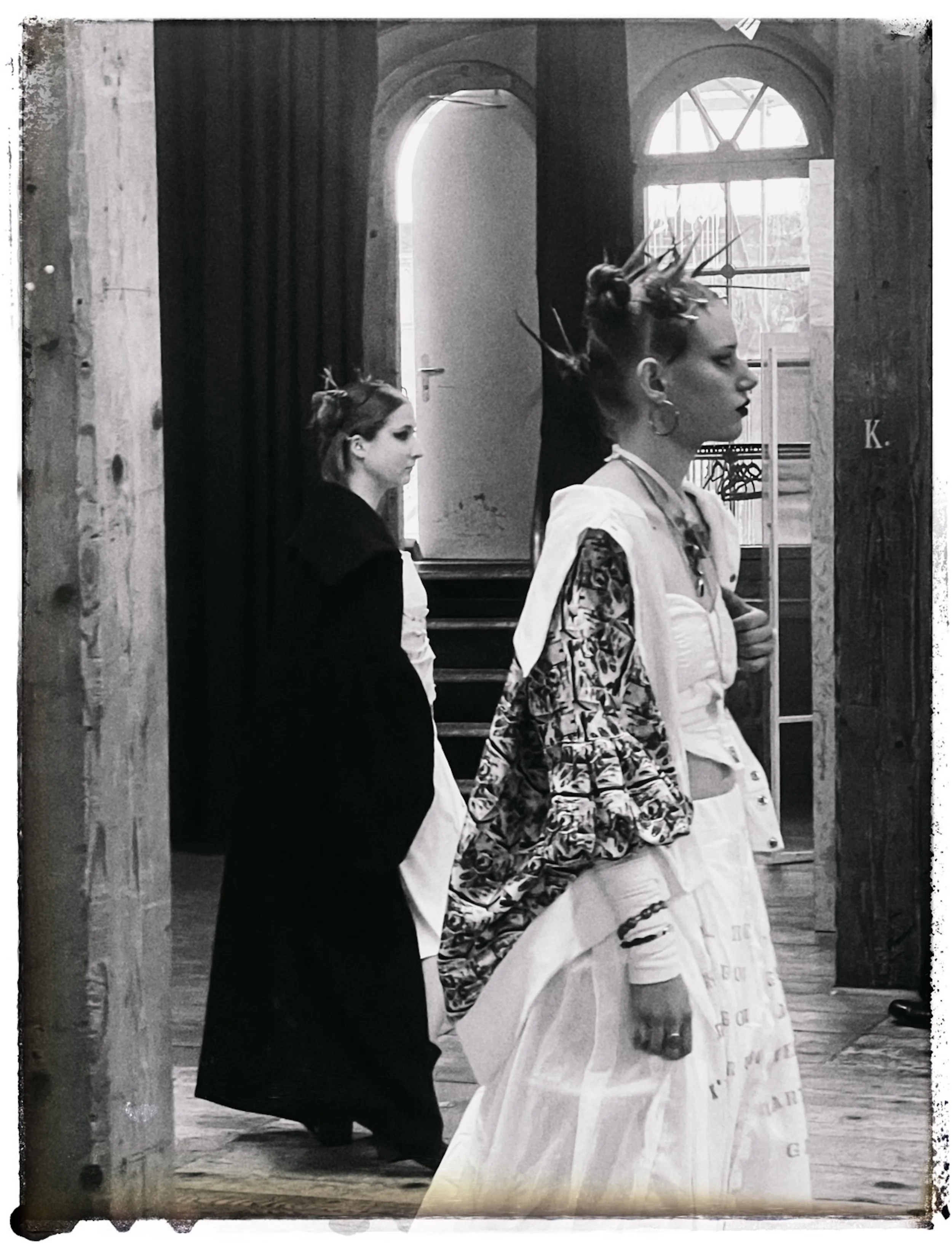

Couture remains a space where designers can articulate the purest expression of their vision (© Edie Lou)

Couture presentations, held in Paris each January and July, occupy a unique place in the industry. Although couture serves a very small client base, its cultural function is broad: it communicates craftsmanship, reinforces brand identity at the highest symbolic level, and preserves techniques that underpin the luxury ecosystem as a whole. Couture workshops - from tailoring to flow to embroidery houses - sustain expertise that later diffuses into ready-to-wear, accessories, and special objects. In this sense, couture is both an economic niche and a cultural infrastructure: a system for maintaining mastery, training artisans, and asserting the artistic authority of a house.

Today, couture also performs a strategic function. As ready-to-wear becomes more commercialized and runway shows increasingly serve marketing objectives, couture remains a space where designers can articulate the purest expression of their vision. (When pret-à-porter emerged in the midi20th century, it was explicitly created to be scalable, manufacturable fashion, in contrast to couture’s one-off, made-to-measure system. So ready-to-wear always been commercial by definition, but what has changed it the degree and structure of commercialization. Pret-à-porter is not just commercial - it is strategically engineered around merchandising logic, global retail calendars, SKU planning, margins, supply-chain optimization, and data-driven forecasting. While in the 1970s-1990s, many ready-to-wear designers still worked with significant creative latitude, and commercial pressure were milder. The creative space today is smaller and the fashion system has become far more commercially disciplined overall. This shift makes couture appear even more like the last space for pure, unconstrained creative expression.

As we said, haute couture is a legally protected and tightly regulated designation overseen be the French Ministry of Industry and the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, requiring participating houses to maintain two Paris-based ateliers staffed with at least fifteen full-time artisans, produce made-to-measure garments for private clients, and present biannual collections in Paris - criteria so resource-intensive that even major global brands often do not qualify. Independent designers therefore cannot formally enter the couture calendar, yet many adopt couture principles in practice: intensive handwork, one-of-one or small-batch pieces, bespoke commissions, experimental silhouettes, and close designer-client relationships. These approaches generate a couture sensibility without conferring haute couture status, enabling some independent houses to build culturally resonant businesses anchored in limited editions, artisanal production, and collector-oriented value. Paradoxically, this position affords advantages that the official couture system cannot fully sustain. While couture is legally defined by craftsmanship and exclusivity, its biannual presentation schedule increasingly pushes couture houses toward runway-like dynamics - show-driven visibility, press cycles, and narrative signalling that resemble ready-to-wear spectacle. Independent brands, by contrast, are not bound to these institutional rhythms: they can set their own timelines, define their own craft standards, design outside seasonal pressure, and build ecosystems grounded in authenticity and specificity. However, the criteria of the Chamber Syndicale de la Haute Couture et de la Mode are strictly enforced, and only a small number of officially recognized houses are allowed to participate; independent brands cannot enter the couture calendar unless they meet these institutional requirements which is extremely rare.

Fashion is a multi-layered system, not a single creative act (© Edie Lou)

Collection Development as System, Strategy and Cultural Practice

Despite the diversity of outputs in the contemporary fashion system - commercial ready-to-wear, runway collections, and haute couture - each form follows a coherent developmental logic shape by scale, resource, and institutional context. Fashion is a multi-layered system, not a single creative act. It emerges from design structures - the creative and conceptual work - craft and technical labor - pattern cutting, sewing, construction - and industrial organization - manufacturing, distribution, institutional systems. The main point is that fashion is produced through interdependent layers of labor and institutional frameworks, not spontaneous creativity.

For large luxury houses, collection development unfolds within a complex corporate structure: vertically integrated supply chains, multiple seasonal deliverables, global distribution networks, and the need to maintain consistency identity across all consumer touchpoint. In this environment, ready-to-wear functions as a strategic signal rather than a profit engine, runway collections operate as cultural communication, and haute couture sustains artisanal authority. Each category fulfils a distinct purpose within an ecosystem where visibility, symbolic value, and long-term brand equity outweigh the financial performance of any single line - a dynamic that Jennifer Craik identifies as central to fashion’s cultural economy. For her fashion’s value is not solely economic and symbolic meaning, identity formation, and cultural influence are central. She explains that brands and designers operate within a system where aesthetic authotrity, cultural capital, symbolic power, and media visibility, all carry economic consequences over time, even if a specific garment or runway collection does not generate immediate profit.

Independent designers operate within a fundamentally different structure. Without diversified product categories, global retail networks, or corporate underwriting, their collections must perform multiple functions simultaneously: establishing an artistic voice, producing sellable garments, and building a community around the brand. Angela McRobbie’s analysis of designer labor and cultural production is particularly relevant here: she notes that independent fashion work combines creativity, entrepreneurship, and social networking within highly precarious conditions. Their runway or showroom presentations - when they choose to stage them - are often hybrid forms that merge creative exploration with commercial pragmatism. Samples may be produced in limited quantities, pieces may move directly form show to small-batch production. For large luxury houses, this often means integrating commercially viable silhouettes into the show to support seasonal messaging, while the more conceptual pieces remain archival. For independent labels, the runway frequently functions as both presentation and product reveal, with show pieces refined and adapted into the versions that enter small-scale manufacturing. In both cases, the collection’s narrative must generate enough cultural resonance to sustain visibility, relevance, and commercial demand.

But for independent labels the aesthetic narrative must carry enough resonance to sustain both cultural presence and economic survival. Independent brands rely on condensed creative labor and intimate relationships with ateliers, suppliers, and audiences. Their systems are smaller, but often more cohesive, specific, and socially grounded, navigating highly precarious working conditions that require constant cultural production and self-management - reflecting the “cultural intermediaries” McRobbie describes. (Cultural intermediaries are people who sit between production and consumption. They create taste, generate cultural meaning, and help audiences interpret what a brand and designer represents, they are a bridge and legitimizing certain tastes and adding symbolic value to goods. As McRobbie argues, independent fashion scenes rely especially on dense, personal networks of intermediaries - making their ecosystems smaller, more intimate, more community-driven.)

Collection development is not a linear process but as a system of interlocking practices (© Edie Lou)

In the contemporary industry, collection development is therefore best understood not as linear process but as a system of interlocking practices - creative, technical, economic, and symbolic. An interplay between craftsmanship, institutional structures, and indsustrial realities. Luxury houses use this system to project authority, maintain global coherence, and manage vast product visiblity and institutional space through scale, marketing power, and consumer demand - a dominance reinforced by consumer expectations and media attention. Independent designers, by contrast, work within smaller, more agile systems that rely on concentrated expertise, direct relationships with ateliers and suppliers, and communities that value specificity over mass visbility. Haute couture sustains the craft infrastructure; runway collections refine the symbolic language; commercial lines stabilize the business. Together, these forms create a fashion ecology in which identity, craftsmanship, and commercial strategy intersect and coexist.

Yet the system itself is changing. As global conglomerates continue to operate through legacy structures - seasonal calendars, mass distribution, and industrial scale - their models increasingly show signs of structural obsolence. In contrast, independent and locally embedded brands present a future-oriented alternative: small, culturally coherent, ecologically aligned, and socially grounded. Their scale allows them to define their own rules, build direct relationships with audiences, and cultivate meaning through specificity rather than spectacle. By creating ecosystems rooted in community, craft, and cultural coherence this emerging landscape can strengthen the resilience and relevance of fashion.

For sure, the future of fashion will not rely solely on the traditional runway model. Its economic and ecological cost has become disproportionate to its functional value: major houses invest millions in temporary environments and events that last for minutes, and the environmental footprint of sets, transport, and production contradicts the industry’s stated sustainability goals. At the same time, digital visibility increasingly outperforms physical reach, undermining the rationale for maintaining such large-scale spectacles. While independent brands are often positioned as alternatives, their significance lies not in replacing conglomerates but in revealing that fashion can operate without dependence on the runway as an industrial institution. Of course, the runway will not disappear overnight. Even as the industry moves toward more sustainable formats, the traditional show will continue to coexist for a while simply because society adapts slowly.

But the real significance and opportunity for independent fashion brands is that they prove the fashion system can function differently. They show that a brand can survive without staging large institutional fashion shows, and that design can build audience and revenue without relying on traditional runway cycle, PR machinery, or Fashion Week validation. The most plausible direction for the future is a fragmentation of formats - smaller, localized; archival-based storytelling; and purpose-driven events that justify their material impact. Whether the traditional fashion show will remain central is unclear, but its status as the unquestioned foundation of the system is already fading. Instead of huge productions in Paris, Milan, London, and New York, more designers will choose intimate studio presentations, community-focused events, collaborations with local ateliers or cultural spaces.

Brands will increasingly blend limited physical events (pop-ups, salons, micro-runways) with digital tools (video lookbooks, livestream, augmented “look-ins”. This allows brands to show collections without the waste and cost of a conventional show. Instead of staging new shows every season, some brands will rework archive pieces - no new fabric production, no new dyeing or finishing, drastically reduced transport and energy use, zero contribution to overproduction. In sustainability terms, the greenest garment is the one that already exists. Archive work is the best expression of this principle. It also strengthens a designer’s identity, it allows a brand to evolve its language without chasing trends, it deepens a narrative, and it foregrounds craftsmanship over novelty. This is by the way why the most respected designers like Kawakubo, Margiela, and Yamamoto return to their archives - not only for their craft but for their artistic and intellectual authority. It is also one of the most rational, future-oriented directions the industry could take, obviously. It respects the planet, it strengthens brand identity, and it reduces risk in an industry drowning in excess. If the future has any clarity at all, it’s this: make less, mean more, and build from what already exists - slow but steady. Steady, as she goes.

So, but for now, this is the map: how ready-to-wear, runway collections, and haute couture come together and reach the stage. It is an overview rather than a full account; the actual system is far more complex, layered, and variable than any single article can fully contain.

https://archive.org/details/faceoffashioncul0000crai

https://archive.org/details/fashion0000brew

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/34145565-paris-fashion

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300189537/the-mechanical-smile/

https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/12216

https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=haute+couture+institution&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8

https://www.fhcm.paris/fr/notre-histoire

https://londonfashionweek.co.uk

https://milanofashionweek.cameramoda.it/en/calendar

https://www.ucpress.edu/books/the-fashion-system/paper

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/five-ways-reduce-waste-fashion-industry

https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2009-12/Global_apparel_value_chain_0.pdf

https://unctad.org/news/seizing-opportunities-circular-economy-textiles

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/key-concepts-for-the-fashion-industry-andrew-reilly/1115448081