PULP 2025: a retrospective

As the year draws to a close, we’re taking a moment to reflect, pause and look back at what has taken shape here on ELS’s editorial platform, PULP. PULP was born on January 1, 2025, as an invitation to pause, reflect, and think more deeply about how fashion reflects social values; how trends, images, and symbols influence behavior; how they connect us to labor, materials, and the world; how they support identity, memory, comfort, and confidence; and how we participate in or resist what culture asks of us. PULP welcomed - and obviously still does - readers into a space where authenticity, creativity, and intentional living intersect; a journal shaped by the belief that reflection creates meaning, and that meaning has the potential to create change in the world for the better.

As the year unfolded, PULP remained loyal to that founding impulse. Each article moved beyond trend and aesthetics toward the deeper structures that shape fashion as a living system - social, cultural, ecological, and human - drawing on the work of thinkers such as Judith Butler, Hannah Arendt, Susan Sontag, Byung-Chul Han, Silvia Federici, and Pierre Bourdieu. The journal kept asking how fashion actively shapes our everyday life - how a garment is created, lived in, and understood. Fashion was explored as a social and symbolic system, as a field shaped by pressure, acceleration, and performance, and as a space where responsibility, dignity, image and interpretation all intersect. Through this lens, PULP returned to a set of recurring questions: What is fashion really - an industry, a language, a system, a cultural force? How is value created, perceived, and sometimes distorted? What does it mean to treat materials as part of living systems, not just inputs in a supply chain? How do clothes participate in shaping identity and meaning? And what does ethical practice look like in real, lived systems? What does responsibility look like inside real supply chains - when Human Resources is translated back into what it really is: people making our garments?

Beneath all of these inquiries - often unspoken yet always present - lay a final question: How do these relationships unfold over time? Rather than celebrating novelty for its own sake, PULP approached fashion as infrastructure of meaning - something that exists at the intersection of culture, psychology, economics, identity, and ecology. This way of approach has shaped the journal’s work. Seen in this light, fashion is no longer reducible to surface or style; it stops being a superficial topic that some people claim not to care about and reveals itself as something none of us actually live outside of - even indifference is expressed through what we wear.

PULP - Paper Unites Labyrinthine People (© Edie Lou)

Value - Beyond Price

A central thread this year was value - not as price or status, but as lived significance. The writing examined how luxury, symbolism, aspiration, and performance can obscure the realities of labor, craft, and environmental impact behind them. Of course, none of this is new. Most of us already understand that the image of fashion can and does hide the human and ecological realities beneath it - but the fact that we have to keep saying it is precisely the point. If these problems had been resolved - if care, dignity, and accountability were structurally secured - there would be no need to return to the subject. But obviously, we are not there yet. And so the work continues, not to repeat the slogan, but to keep the conversation alive until it is no longer necessary.

PULP kept returning to the simple but difficult question: What are we really buying when we buy fashion? What remains unseen beneath the performance of “worth”? Why is theatre so often mistaken for substance? Why do spectacle, image, and presentation so often get confused with real value, quality, or integrity? And people are often willing to pay disproportionately for the concept of belonging - for the signal that they are “inside” the right story. Rather than settling for critique, PULP searched for a more grounded vocabulary of value - always aware that we are part of the same system we are examining. The inquiry was not about judging others - generating bad feelings - but about understanding the structures we ourselves participate in. What emerged was a sense of value rooted in relationship, dignity, longevity, and cultural contribution, where worth is not a purchase signal but a reflection of the people, labor, skill, and relationships that made it possible - this is still fashion, of course, but understood with more honesty and care. And the logic extends beyond clothing: the same orientation applies elsewhere in life: a commitment to care, humanity, and dignity in the systems we inhabit.

Clothing as a cultural language (© Edie Lou)

Culture, Identity, and the Self in Motion

PULP also considered clothing as a cultural language - something that does not merely reflect identity, but gradually shapes it through how we dress, move, and belong. The articles followed how meaning accumulates around dress, how clothes stabilize or unsettle the self, and how garments hold memory and narrative. Fashion was understood as a semiotic system - a language of signs that reflects society and, at the same time, helps shape identity and culture. Clothing does not simply mirror who we are; it also influences how we see ourselves, how we behave, and how we are read by others. A language of signs through which societies articulate class, aspiration, gender, power, restraint, rebellion, belonging, and distance. A silhouette, a fabric, cut, a heel hight, a hemline - each carrying cultural memory and symbolic charge. When a garment is worn, those meanings do not remain theoretical. Garments influence how others respond and, in turn, how the wearer comes to understand themselves. Identity is not merely expressed through dress - it is continuously negotiated through it.

Meaning accumulates through repetition and recognition. Uniforms create social order. Taste codes separate communities. Subcultures develop highly specific style codes, where even small choices - a fabric, a silhouette, a way of wearing - communicate belonging and shared meaning. And garments themselves become repositories of narrative: the coat worn through a difficult winter, the dress associated with a turning point in life, the shirt tied to a first kiss - still alive. Clothing stabilizes identity at times, offering continuity and coherence. At other moments, it unsettles the self. opening space for experimentation, ambiguity, or reinvention. In this sense, fashion is a medium through which the self meets the world - interpretive, relational, and always in motion.

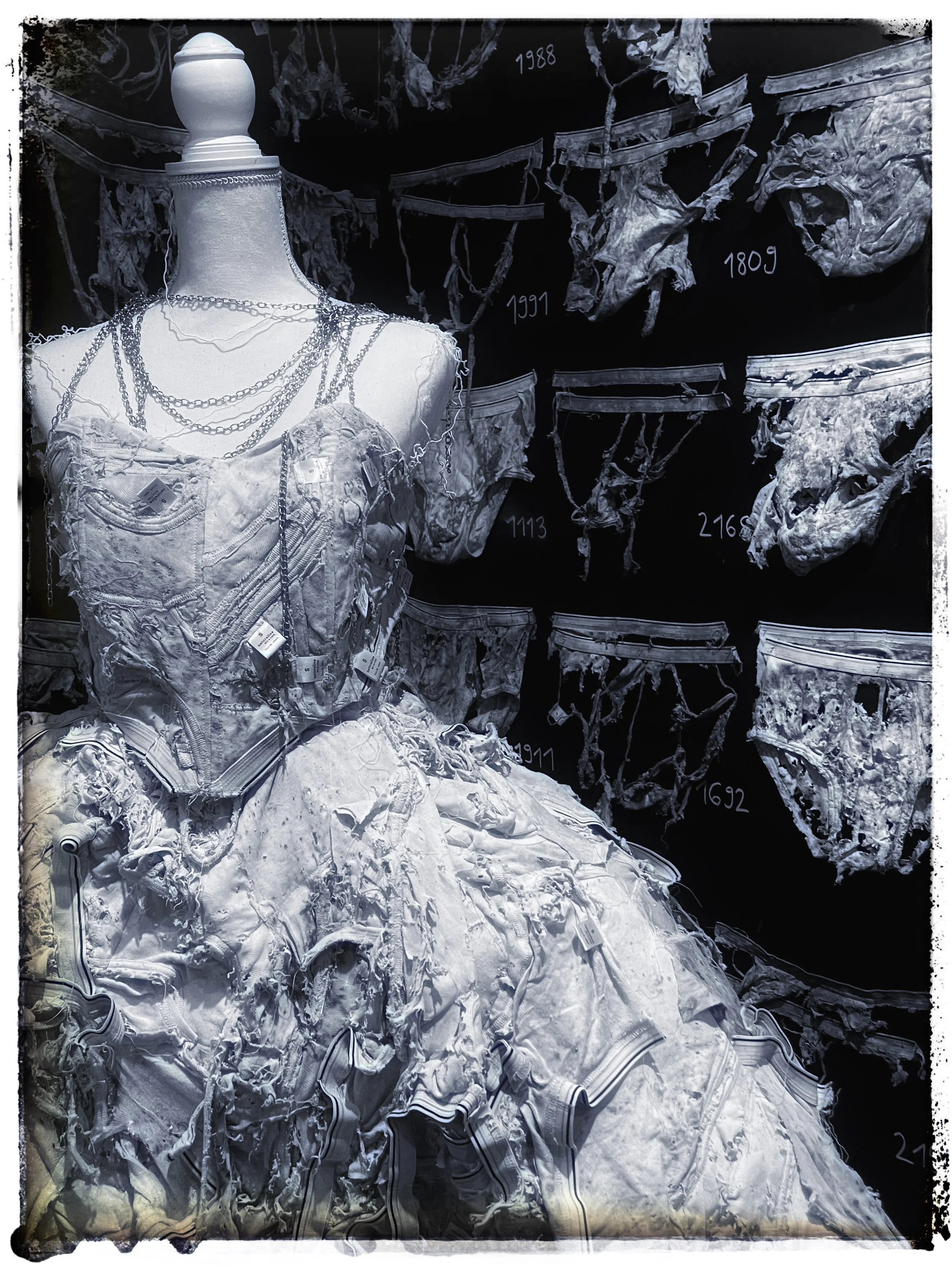

Who and what sustains fashion? (© Edie Lou)

Ethics - Toward Practice

But across the year, one ethical question persisted with insistence: Who and what sustains fashion - and at what cost? Rather than celebrating the language of “responsibility”, the work returned to the material realities beneath it - examining actual working conditions, contracts, cash-flow pressures, decision-making structures, extraction patterns, and lived human experience. Every garment carries human labor, industrial risk, ecological extraction, and unequal vulnerability. The professional language calls it “Human Resources”, yet these are human lives - each with skill, fragility, exhaustion, ambition, and foremost with dignity. To speak about ethics in fashion is therefore not to polish a moral identity, but to recognize the asymmetries upon which the industry continues to depend. Ethics, in this frame, is not posture or moral talk, it is a structural orientation that shapes how decisions allocate risk, value, and care. It asks how design, production, storytelling, and consumption might honor the reality of interdependence - between brands and workers, between humans and ecology, between private desire and public consequence.

Materials and ecological limits were also central threads across the year. Fabric isn’t just a design material. It is part of much larger ecological and social systems - from how it is grown or made, to how it affects workers and environments, and a future after the garment’s life ends. Circularity, repair, longevity, and responsible sourcing were explored as attempts to reconnect fashion to the material realities it depends upon - and to ask what it means to design within limits. The planetary boundaries framework provided a further lens for this inquiry. It makes clear that industries - fashion obviously included - operate inside finite ecological thresholds, and that exceeding those limits has structural consequences.

Alongside these reflections on value, ethics, culture, and materiality, PULP also engaged with the business and marketing dimensions of fashion - how business models, pricing structures, growth expectations, and narrative strategies shape what becomes possible in practice. To understand fashion, honestly, means acknowledging that culture, identity, and aspiration are always entangled with economics and communication - fashion is never only about meaning or only about money - it is always both, simultaneously. That means ethics cannot sit only in storytelling or aesthetics; It has to be built into pricing, production models, growth expectations, and how risk is shared across the supply chain. The question, then, is how to run a viable fashion company while distributing value, pressure, and responsibility in ways that remain human, proportionate, and transparent. Ethical fashion is a discipline of limits - it is only possible if a brand is willing to limit itself. And this is exactly what PULP is working on: to keep examining the boundaries between what is desirable, what is viable, and what remains ethically and socially acceptable to stand behind. PULP exists to think carefully about where creativity, business reality, and ethics overlap - and where they don’t - so decisions can be made consciously.

PULP is not claiming to be ethically perfect (© Edie Lou)

Final Thoughts

The intention here was not to perform ethical credibility, but to examine reality honestly - understanding actual conditions and responsibilities. Importantly, this work is not directed solely toward an external audience. It also serves as internal critique: a reflective practice through which ELS examines its own position within the system and orients future decisions toward ethical coherence. PULP is not claiming to be ethically perfect, superior, or beyond critique, obviously not, it is inside the same system it is analyzing. The purpose of writing is to build the conceptual clarity and language needed to make better decisions in the future. The editorial treats writing and reflection as the first step toward meaningful change: by understanding the system clearly - including ELS’s and PULP’s own role within it - the journal seeks to develop the analytical foundations necessary for more responsible practice to think clearly enough to act differently.

At its heart, PULP has always tried to do something simple: to think out loud. The writing exists so that anyone moving through this world - designers, students, brand owners, makers, readers - might find words for things they already feel, a bit more clarity where everything feels blurred, or a steadier compass when the industry’s noise gets loud. It’s less about having the answers, and more about keeping the conversation open - reflection as something shared and kept in circulation.

So, we carry this spirit with us into the new year - still questioning, still learning, still sharing whatever clarity we manage to find along the way. 2025 has been a year of growth through the work itself; every article stretched us a little further. And we didn’t do it alone. To everyone who read, questioned, encouraged, challenged, or inspired - thank you! PULP isn’t a one-way broadcast - it is shaped by the community around it. Your presence shaped the conversation as much as the writing itself did. Now we begin again - with curiosity intact and the door left open. With that, we step into the new year. Thank you for being here - Happy New Year.